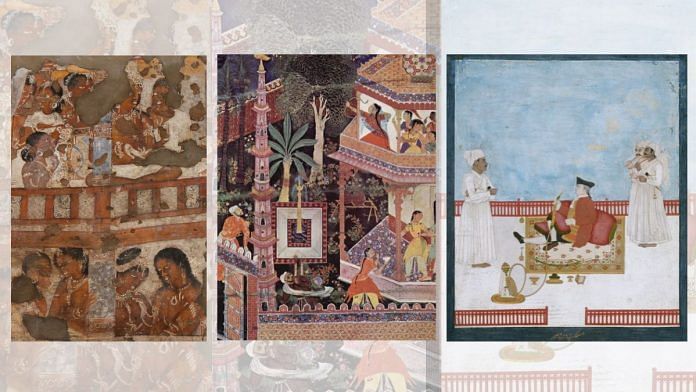

With the current fervour surrounding ‘decolonisation’ in contemporary Indian politics and law, many intellectuals and academics are engaged in furthering this seemingly progressive project. However, a critical examination reveals an absence of substantial positive contributions. Under the pretence of doing positive work, lawyers, authors, and members of the judiciary and executive are merely promoting atavistic and nativistic approaches that fail to propel genuine Indian thought, ideas, or culture forward. The tendency to idealise a pristine past, while sidestepping the complexities and transformative impacts that India has experienced over time, proves counterproductive. There’s plenty of going back to the epics and relics and theorising of an unblemished historical era, but there is a lack of acknowledging the dynamism of Indian culture and thought.

While Hindu nationalists often glorify India’s ancient era as a time of unparalleled achievement in art, science, and global influence, their perspective tends to neglect the substantial impact of colonial-era policies and the modern adoption of constitutional principles in India’s development. This idealised portrayal seeks to revive India’s past greatness as a “Vishwa Guru” or global leader in the 21st century. But removing portions of Mughal history from school textbooks or contentious efforts to rename cities so that they sound more Hindu than Muslim, sparking etymological disputes, do not serve the real purpose of decolonisation. This call to decolonise everything should be used to highlight the multifaceted reality of India’s historical journey, with all its influences. Getting entangled in an idealised past, as is happening now, hinders genuine growth and understanding.

Cosmetic changes, colonial roots

From 1 July, India’s three prevailing colonial-era criminal codes will be replaced by newly crafted statutes bearing formal Hindi titles. Despite claims that this initiative is a break from colonial origins, a closer look suggests otherwise. While the government’s rationale for this change is deeply rooted in the narrative of ‘decolonisation’, this attempt seems ultimately futile.

The essence of these laws continues to reflect colonial-era ideologies and moral conservatism, undermining efforts to foster inclusivity, equality, and justice.

For example, Section 63 of the new criminal code, Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), retains the marital rape exception encoded in Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). Similarly, the archaic language of ‘modesty’ persists in Sections 74 and 79 of the BNS, mirroring Section 354 of the IPC. Such instances represent missed opportunities to implement meaningful change, with new titles serving as mere window dressing for outdated colonial laws.

In the current Indian landscape, the term “decolonisation” appears to have deviated from its original intent. Instead of serving as a tool for dismantling colonial legacies, it has taken a course that is, ironically, antithetical to its initial aims. The term’s broad and varied usage across disciplines has diluted its original meaning, contributing to a complex and sometimes contradictory discourse surrounding the notion of decolonisation.

Reduction to a political tool

For Hindu nationalists, the concept of decolonisation extends beyond dismantling British colonial legacies. It also includes the elimination of what they perceive as the lingering impacts of “Islamic conquests” in India. In their view, acts like the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992 and inauguration of the Ram Mandir in its place symbolise a form of “decolonisation”. They justify removing structures, erasing histories, and renaming cities associated with Islamic rule by claiming to reclaim Hindu heritage and sacred sites from foreign intrusions.

However, removing structures and histories does not signify genuine decolonisation or progressive thinking. Instead, it often perpetuates exclusionary narratives and reinforces divisions within society. The mainstreaming of decolonisation as a political issue reflects its ability to tap into long-standing feelings of colonial humiliation among Indians. By exploiting these sentiments, nationalists garner support for their agenda of cultural and ideological dominance.

Rather than addressing the deeper issues of systemic inequality and injustice, they reinforce divisive narratives and perpetuate exclusionary practices as well as ethnic nationalism.

This manipulation of decolonisation as a political tool deviates from its original intellectual and academic purpose, which was to critically examine and dismantle colonial structures of exploitation, power, and oppression.

Also Read: India’s proposed criminal law codes can modernise justice – if they begin with police first

What are we ‘decolonising’ for?

Decolonisation implies achieving independence from colonialism, which is not an ongoing process, according to philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O Táíwò in his book Against Decolonisation: Taking African Agency Seriously.

Táíwò prompts a critical reflection on the proclaimed independence and sovereignty of nations that continue to engage in decolonisation efforts. He suggests that such initiatives imply the ongoing existence of colonialism. “[T]he concept of ‘decolonisation’ is best understood if we restrict ourselves to conceiving of it as eradicating colonialism,” he writes.

Through his philosophical approach, Táíwò questions the very essence of post-independence decolonisation efforts. He asks that if decolonisation is necessary after independence, does it mean colonialism never ended? In essence, the reader is invited to reconsider the very definition of sovereignty if it necessitates a perpetual struggle for decolonisation. Even though Táíwò takes an Afrocentric perspective, his analogy can be successfully applied to the Indian context where everything seems to be an agent of decolonisation.

We must question the ease with which the decolonisation trope is used without deep attention to the complexity of the issues involved. The whole debate on decolonising laws, literature, language, religion, marriage, and so on is unhelpful and built on a set of confusing notions.

There is no clear reason as to why we need to “decolonise” and nobody points out what is wrong with using knowledge or frameworks derived from the colonial period. Yet, blowing the decolonisation trumpet has gained immense popularity. If this call to decolonise transforms into a wholesale rejection of any facet of the coloniser’s culture, society, politics, or science, it would mean giving up on the idea that all humans are fundamentally connected and the fact that hybridity is the very core of human civilisation.

Such a stance could lead to a return of outdated ways of thinking, identity-based politics (including favouring one ethnic group), and other unacceptable forms of cultural nationalism in postcolonial countries. A phenomenon we are already witnessing in India.

Academics and intellectuals promulgating the decolonisation project must not develop a definition of colonialism so elastic that it no longer has any meaningful boundaries. Indiscriminately labelling anything with even a slight association with the colonisers as an agent of decolonisation is counterproductive. This broad interpretation makes it difficult to determine what success would look like in a decolonised world.

Let’s advocate for a more nuanced understanding of decolonisation—one that acknowledges Indian agency and the transformative power of cultural hybridity. Draftspersons, intellectuals, and academics often gravitate towards this discourse due to its seemingly straightforward narrative. However, we must challenge this narrative and make it more difficult to adopt by highlighting its limitations.

Ayushi Vashisht is a lawyer and DPhil (PhD) in Law candidate at the University of Oxford. She tweets @VASHISHTAYUSHI7. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Excellent! Very relevant

Need more detail

1. How is this author defining modesty then? The writer seems to be a liberal feminist having an agenda to make nationalism a problem while sitting in Oxford as an elite.

2. What is wrong in having a cultural and ideological agenda? Britishers did Brexit with a similar agenda-even today.

3. How would one define or conceptualise de-colonisation sitting in AC rooms writing in British English amongst the colonisers as an elite liberal ?

Kindly answer without getting defensive.

If the current political ideology based on exclusions is taken to its logical end , you will end up with nothing but a new caste system where the followers of minority religion will be treated as lower caste citizens and all Hindus become upper castes.

Decolonization means nothing if you dismiss something without studying it. There were positives and negatives in colonization. To reject positives from it and reinvent a revisionist understanding of history based on hindsight is travelling in the wrong direction. Not something seekers of truth should undertake. This is the land where we believe that knowledge can come from all directions. In pursuing decoloniality , we loose that belief for our own peril.

I hope you have never written from an AC room.

decolonisation can wait – de-Islamization of bharatham needs to continue at a faster pace.