The messy piles of yellow-framed National Geographic magazines under my bed, jostling for space with old issues of the red-rimmed Time, were a window to life outside pre-liberalised India. The magazines, along with Prannoy Roy’s The World This Week on Doordarshan, completed my informal childhood education of international affairs.

But it was Nat Geo with its photos of pygmies and pyramids, gorillas and giraffes, temples and tempests, and maps and cities—so different from Bombay—that drew me back, again and again. It was where I first learned about dinosaurs. It was where I met Tut, the boy pharaoh of Egypt. I discovered piranhas in South America, and birds so brilliantly coloured in the Amazon rainforest. I read about China and Russia, of Hitler and Europe.

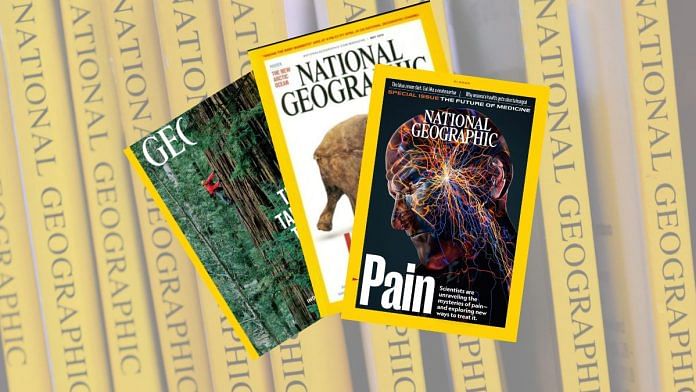

It was where I discovered that an entire species can die. And magazines as well. Extinction almost always starts slowly; it’s unfolding within National Geographic’s yellow frame.

National Geographic will no longer be sold on newsstands. Instead, the focus will be on subscriptions and its digital offerings, it announced in June. After 135 years since its first issue, the magazine is struggling to adapt to a new brave world, driven by reels and cat memes. Announcements of layoffs are made with depressing regularity.

In the latest round, its last remaining staff writers were laid off as part of cutbacks under its owner Walt Disney Co. Not one of Disney’s white-washed animations peddling fake dreams or Star Wars spin-offs can hold a candle to National Geographic’s magic. And like most other services in this gig economy ecosystem, the magazine will rely on freelancers or stories put together by its remaining editors, reported The Washington Post.

National Geographic’s scope is breathtaking with its coverage of cultures, societies, wildlife, technology and even space. At first, I simply flipped through the brittle pages dulled yellow with age, marvelling at the photospreads. But then I started reading the dispatches from different worlds.

Also read: Black Mirror was right about dark tech & future. Crypto to AI, we are already living in it

Through the yellow frame

The Afghan Girl (1985) remains one of the most talked about issues, but I don’t remember it. Perhaps there was a copy at home, sourced from the friendly neighbourhood raddiwalla (scrap dealer) like other ‘foreign magazines’ in my house, but it never registered in my world.

Instead, I vaguely recall reading David Doubilet’s exploration of Suruga Bay in Japan, and an old issue with an article by Jane Goodall on chimpanzees. One photo had her sitting on the ground, clad in a khaki shirt and a pair of shorts, taking notes while a group of chimpanzees played nearby.

Each issue was a real-life embodiment of believing in six impossible things in real life. I wanted to be a chimpanzee researcher (I still do). After that I decided to be a deep-sea diver, then a whale researcher, then an explorer and a writer, a photographer, and a filmmaker. I wanted to go to Borneo with a pitstop at NASA.

As I grew older, the wonder was tinged with envy for people who got the opportunity to travel and write for the yellow-framed magazine. And as a teenager, I was made aware of the magazine’s many problems–its racism, the predominant male voice and gaze through the lens.

A 1997 cover on India turning 50 cemented this view. For the first time an image from my city, Bombay, was framed on the cover. It was a cropped photo of a child whose face was painted red. Taken by Steve McCurry— whose photographs of India and the subcontinent graced almost every issue in that decade—it was captioned, ‘Dusted in red powder, a young Indian boy joins in the traditional Hindu festival of Ganesh Chaturthi in Mumbai (Bombay).’ My city was finally on the cover but the photo was not representative of either Mumbai or Ganesh Chaturthi, a festival I celebrated every year with neighbours.

What followed were conversations with friends about whether National Geographic exoticised cultures of other countries like India for its predominantly white American audience.

Over the years, I stopped seeking the magazine at second-hand bookstores, raddiwallas, and roadside vendors. It was a gradual decline in interest. And when Discovery and Nat Geo Wild started airing on TV, I was more than ready to make the transition.

The last time I held a copy of National Geographic was months before the pandemic. Climate change was the theme, and the voice of breathless discovery that many of the old issues of my childhood days had disappeared. Instead, every page sounded an alarm in short, simple headlines: ‘Ice is melting fast.’ ‘Wildlife is already hurting’. ‘Weather is getting intense’. The accompanying photo of the war in Syria made no sense until you read the caption. It argued that the war “was ignited in part” by a historic drought that drove farmers to cities.

But the message of hope was not completely drowned out in doom and gloom with the story, ‘We can do something about it’.

The magazine’s first issue was published in October 1888 as the official journal of the National Geographic Society, a group of 33 scientists, including Alexander Graham Bell. The society funded expeditions and explorations around the world from Mt Everest to the Mariana Trench. It has an archive of around 11.5 million images.

What has remained constant is the rectangular yellow logo. Some theories say it’s the shape of a certificate of honour, while others see it as a photo frame or window pane offering a peek into the world beyond. My favourite is the yellow denotes the sun, which sustains life on Earth.

May it always shine bright.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)