Five years of the Narendra Modi government have been marked by constant executive-judiciary tussle. But if you think that’s a first, you are mistaken. Sixty years ago, the sensational Nanavati case saw the first head-on collision between the executive and the judiciary in India.

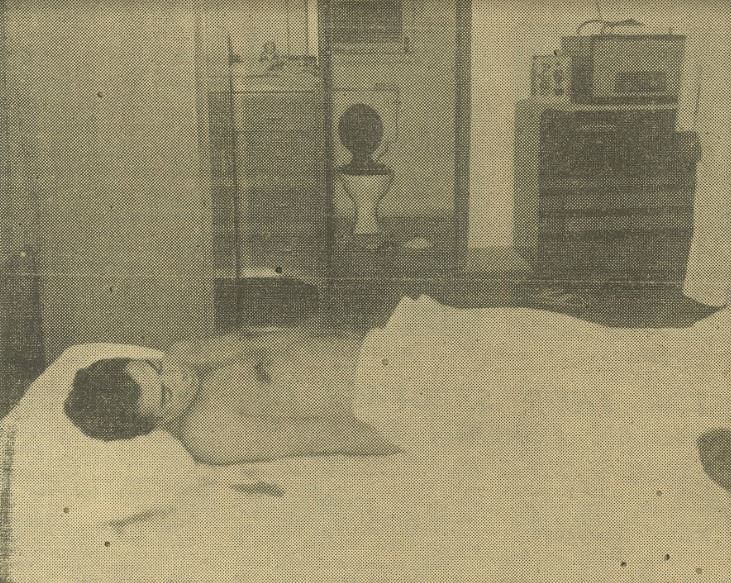

On 27 April 1959, Naval commander Kawas Nanavati stormed into an exclusive Bombay flat, and shot dead his English wife Sylvia’s businessman lover, Prem Ahuja. Three shots in less than three minutes, but they created legal history and an indestructible legend.

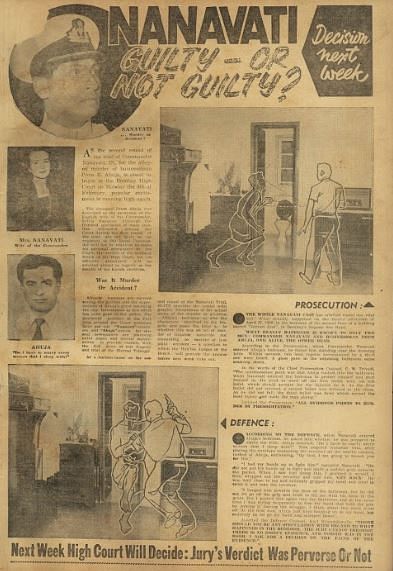

The trial was marked by thriller-grade twists and turns, ended the jury system, called for the setting up of two Constitution benches, forced the intervention of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and fuelled unprecedented public hysteria. Those hot-blooded shots have reverberated noisily through the intervening decades, and seem to be in no mood to taper off.

The Nanavati case was not just the first upper-class crime of passion, it also set in motion the temerity with which the rich and influential would try to subvert justice. It was the first ‘trial by media’, and the first crime to get jumped up to ‘national event’. It pioneered the fail-safe trend of exploiting the uniform and patriotism for less noble ends.

Also read: Like Aarushi Talwar, no one killed Bibi Jagir Kaur’s daughter

We’re rich & influential; To hell with law

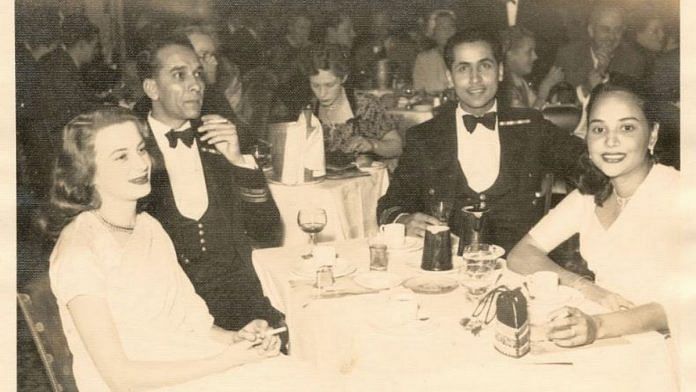

Kawas Nanavati belonged to the time’s most exclusive club. He was a Bombay Parsi when this minority commanded the heights of industry, law, medicine and culture. Any shortfall was more than made up by his other sphere of influence: the Navy and its political extension.

The Commander was the blue-eyed boy of then-defence minister V.K. Krishna Menon; he pompously told The New York Times that he had leaned so heavily on the system because ‘I did not want the stain of turpitude to destroy the career of so promising an officer’. Admiral R.D. Katari flew down in an official jet to endorse his character at the sessions trial, a gesture not accorded before or since. Prime Minister Nehru himself pacified the Delhi Press baying at the unconscionable favours being granted to a convicted killer.

Every decade since has been bloodied by a similar crime, or three, involving those with friends in high places, or political heavies themselves.

4 December 1973: Vidya, wife of Dr N.S. Jain, eye surgeon to then-President V.V. Giri, was brutally stabbed 14 times as the couple got into their car. The contract murder was plotted by the doctor and his long-time mistress, Chandresh. Appeals against the life sentence handed to Jain finally prevailed. But the killers were hanged.

28 July 1988: Eight-time national badminton champion Syed Modi was shot as he left a Lucknow stadium. A conspiracy-to-murder charge was filed against his wife, Ameeta, and her lover, Sanjay Singh, adopted heir to the Amethi ‘kingdom, a friend of Rajiv Gandhi, and the Congress leader who crossed over to the Janata Dal, the BJP and back to INC. In 1990, both were absolved; investigating officers confided that the case was ‘scuttled’. Even the ‘actual killer’ was exonerated. In 1991, Dev Anand made a thriller based on the murder, Sau Crore. Later, Sanjay married Ameeta; his wife Garima challenged the marriage. After lying low, Sanjay re-entered politics – and inducted Ameeta as well. She was the successful BJP candidate from Amethi in 2002, and in 2007 as a Congresswoman. Garima contested against her in 2017, and won.

2 July 1995: Naina Sahni, a Congress worker, was killed by her husband Sushil Sharma, then-Delhi Youth Congress youth president who suspected her of infidelity. Then he famously tried to burn the body in the terrace tandoor of a friend’s restaurant. The trial court sentenced him to the gallows, which was upheld by the high court. The Supreme Court commuted the death sentence and said it wasn’t an offence against society. Maxwell Pereira, the Delhi top cop who’d investigated the case, wrote a book on it in 2018.

Also read: Delhi Crime: Why watch a Netflix series on the intensely reported Nirbhaya gangrape case

23 January 1999: Journalist Shivani Bhatnagar was bludgeoned to death in her rented Delhi flat. Ravi Kant Sharma, IGP Prisons, Haryana, the main accused in the case, absconded and surrendered in 2002, but was acquitted in 2011 for lack of evidence in a tardy trial. But Sharma’s wife accused BJP’s powerful and charismatic minister Pramod Mahajan of framing her husband. Since this bombshell came soon after the petrol pump and land allotment scandals, the party went into hyper damage control with L.K. Advani and even Prime Minister Vajpayee coming to the defence of Mahajan, whose resignation was demanded by the Congress. In 2006, Pramod was shot at home by his enraged brother Pravin, also believed to be a crime of passion.

30 April 1999: Jessica Lal was shot dead in a swishy Delhi night club. Scores of witnesses pointed to Manu Sharma, son of Venod Sharma, an influential Congress leader from Haryana, but were allegedly silenced, and Manu was acquitted by a trial court. However intense media and public pressure forced the Delhi High Court to reopen the case, and after a 25-day fast track trial, the brattish murderer was sentenced to life in 2006. A 2011 movie on the incident was titled No One Killed Jessica.

16 May 2008: Aarushi Talwar, 13, was found in her bed with a slit throat. The body of the family servant Hemraj was discovered on the terrace. Her dentist parents were the ‘obvious’ accused, and were sentenced to life imprisonment in November 2013 after a convoluted trial. Avirook Sen, who had bucked the vicious media trend while reporting for Mumbai Mirror, wrote a book, followed by Meghna Gulzar’s Talvar, both in 2015. Rajesh and Nupur Talwar were acquitted in October 2017 on account of shoddy evidence.

It might be difficult to upstage the case of Sheena Bora, 25, whose 2012 murder was accidentally discovered in 2015. The ghoulish killing and the cover-up were sensational enough, but have now become a mere side-bar to a politically sensitive scam centred on INX Media founded in 2007 by Indrani Mukerjea, the main accused in the Sheena Bora murder case, and her third husband Peter Mukerjea. Ironically, in 2008, The Wall Street Journal listed Indrani among the 50 Women to Watch.

Judiciary vs executive: The jury’s still out

‘Unusual and Unprecedented’ thundered Justices Shelat and Naik when, on 11 March 1960, Sri Prakasa, Governor of Bombay ‘in exercise of the powers conferred on me by Article 161 of the Constitution of India’ suspended the life sentence they had handed to Commander Nanavati – just four hours earlier. With it, a case which began in a mundane adulterous bed moved surrealistically to a lofty Constitution Bench. Two actually.

The first was presided over by Chief Justice H.K. Chainani of Bombay to look into the validity of the obstruction to serving the warrant to Nanavati. This was the first time that any governor had exercised this power, so this was the first such hearing. Arrayed were the legal heavies, H.M. Seervai as Advocate General for the State; Rajni Patel with Nani Palkhivala and S.R. Vakil of Mulla & Mulla for the accused.

The bench concluded that the order of the Governor was not unconstitutional, but firmly added that the ‘wide and unfettered’ powers under Art 161 are ‘not intended to be used arbitrarily’ and ‘not to circumvent the due processes of law … or to short circuit legal processes…’.

The second such bench was presided over by the Chief Justice of India, B.P. Sinha, himself, tasked with interpreting how the executive’s constitutionally granted power is to be harmonised with that of the Supreme Court under Article 142.

Also read: Isn’t 20 years enough to reform? Tandoor case convict’s release provides the answer

This gingerly divided space has frayed dramatically over the decades. Between 1966 and 1977, Indira Gandhi imperiously denounced judges and judgments to make the judiciary submit to her. Remember 1975, when the Allahabad High Court’s Justice Jagmohan Lal Sinha set aside her election to the Lok Sabha – and triggered the Emergency. Just last April, the Congress-led opposition called for the impeachment of then-CJI Dipak Misra, which was dismissed by Vice-President Venkaiah Naidu.

A long-standing turf war has simmered over the power to appoint or remove judges – which can serve the executive’s agenda. In December 1981, Justice P.N. Bhagwati had declared that the CJI’s recommendations on appointment of transfers can be refused ‘for cogent reasons’. But the fractionated coalition governments of the late ‘80s tilted the balance towards the more monolithic judiciary.

A tectonic shift occurred again when, within three months of its sweeping 2014 mandate, the NDA government moved the Constitutional Amendment bill to scrap the two-decade-old collegium system, and provide for a National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC). In 2015, the SC struck the NJAC Act down as unconstitutional. The dingdong battle continues.

But coalition governments also get paralysed by the same conflicts. This has encouraged judicial intervention, ‘activism’ or even ‘overreach’, a contentious leitmotif of our times.

Trial by media

Like a tabloid, Mumbai’s staples are sex, crime and money, with the street as arbiter. All these coalesced in the Nanavati case, making it easy for a tabloid to run away with it. Russi Karanjia’s Blitz played to the gallery with an entire orchestra of emotions. Right to the OTT present, it has been the template for covering crimes, especially of passion. We see nightly on television how anchors become judge, jury and hangman too. The difference is that Karanjia, along with the equally flamboyant defence lawyer Karl Khandalavala, cast the accused in the image of an Unalloyed Hero, Lord Rama-like avenging the seduction of his wife, but remaining noble in the face of gross betrayal.

No such glory for the subsequent accused. The media savaged Aarushi’s parents, ignoring the holes in the prosecution. It went to town on the ‘300 pieces’ into which a vengeful Maria Susairaj and her naval boyfriend chopped up Neeraj Grover; Maria was exonerated of the murder charge. Indrani Mukherjea has already been damned as the she-devil incarnate.

Also read: Police leaks led to trial by media in Bhima-Koregaon case: Quotes from dissenting judge

Media has also copied the craft: Blitz’s graphic time-lines, sinister woodcut-style illustrations, screaming headlines, played-up ‘scoops’ – and dubious sources. Even today’s favourite of taking the story ‘offline’ has its font in the campaigns fronted by Karanjia to drum up support for the backroom parleys by Nanavati’s politically influential friends for his pardon.

Sabeena Gadihoke’s doctoral thesis observed that ‘The Nanavati coverage eclipsed other news of the time, and… reframed the definition of a national event’. The Indian Express ‘compared it to Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination as well as sensational public trials such as the Bhowal Sanyasi, Bhagat Singh, the Meerut conspiracy cases and the Tilak sedition case’. This historic trial’s ‘long shadow’ hovers over the relentless headlining of its successors.

And here’s the latest plug-in. Nanavati’s spin doctors blatantly exploited the uniform to bedazzle the jury – and swooning women. He arrived daily in court dressed to the hilt, right down to the ceremonial sword. Khandalavala and Karanjia played upon his service to the country: to seduce the wife of such a man was little short of ‘anti-national’. The films based on it, Yeh Raastey Hain Pyar Ke (1963), Achanak (1973) and Rustom (2016) all valourised the ‘vardi’ to heighten the hero’s appeal. But there’s one departure from the ‘Balakot Redemption’ replayed across the current electoral landscape. In the Nanavati case and all its cinematic avatars, the uniform burnished the legitimate wearer; it wasn’t commandeered to pump up a wannabe political legend.

Bachi Karkaria is author of the critically acclaimed bestseller, In Hot Blood: The Nanavati Case That Shook India (Juggernaut, 2017). Views are personal.

All rare pictures are courtesy In Hot Blood: The Nanavati Case that Shook India (Juggernaut).

The French would have forgiven this crime of passion. To be perfectly honest, so would I …