Whether it’s flooding every monsoon or dipping groundwater levels in the summer, Gurugram has a problem. And Delhi is hardly any better, with groundwater reserves predicted to run out by 2020-21. Shrill alarm bells haven’t been able to wake the Haryana and Delhi governments from slumber.

And while the Narendra Modi government may have promised ‘Nal se Jal’ for every household by 2024, time is running out for India’s capital region. The one thing that could have helped — the Najafgarh jheel — is now dismissively called the Najafgarh nala.

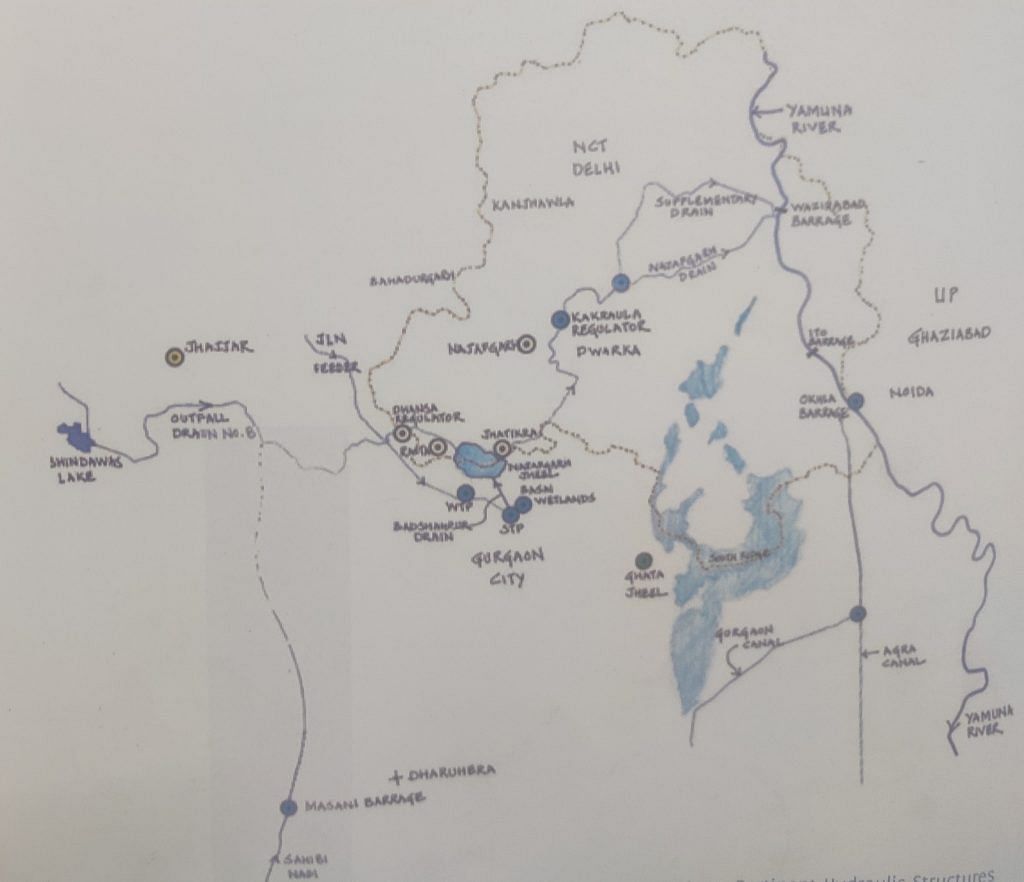

The Najafgarh jheel is the second-largest waterbody in the area after the Yamuna river, and has been feeding Delhi NCR for decades. But you won’t recognise it anymore — it resembles nothing more than a waterlogged nala. Once spread over 220 sq. km., the Najafgarh jheel has now shrunk to just over 7 sq. km.

A dire situation

How did we get here?

In just four years, 2014-18, groundwater extraction in Gurugram increased by 308 per cent, according to government records. In 1974, you had to dig an average of 21.6 feet to get water. Now, you have to dig 91.8 feet.

In Delhi, groundwater resources of seven districts have been categorised as over-exploited — and the South Delhi extraction rate stands at 243 per cent.

There are three intertwined solutions to this — reviving water bodies, catching rainwater and recharging aquifers. Water bodies are the catchment areas for rainwater. They also safeguard settlements from inundation by floods. And they are also the fountainhead of aquifer recharge. A legion of city planners and lawmakers, clearly egged on by avaricious developers, chose to turn a blind eye to this crucial information. That led to the ruin of Delhi and Gurugram’s biggest natural water reservoir, rainwater catchment area and groundwater recharger — the Najafgarh jheel.

Also read: Mumbai record rainfall since 2005 exposes same old issues as city refuses to learn lessons

Jheel to canal

The Najafgarh jheel used to be an immense wetland lying in Gurugram and Delhi. It was fed by the Sahibi river and floodwaters from Gurugram, Rewari, Jhajjar and north-west Delhi.

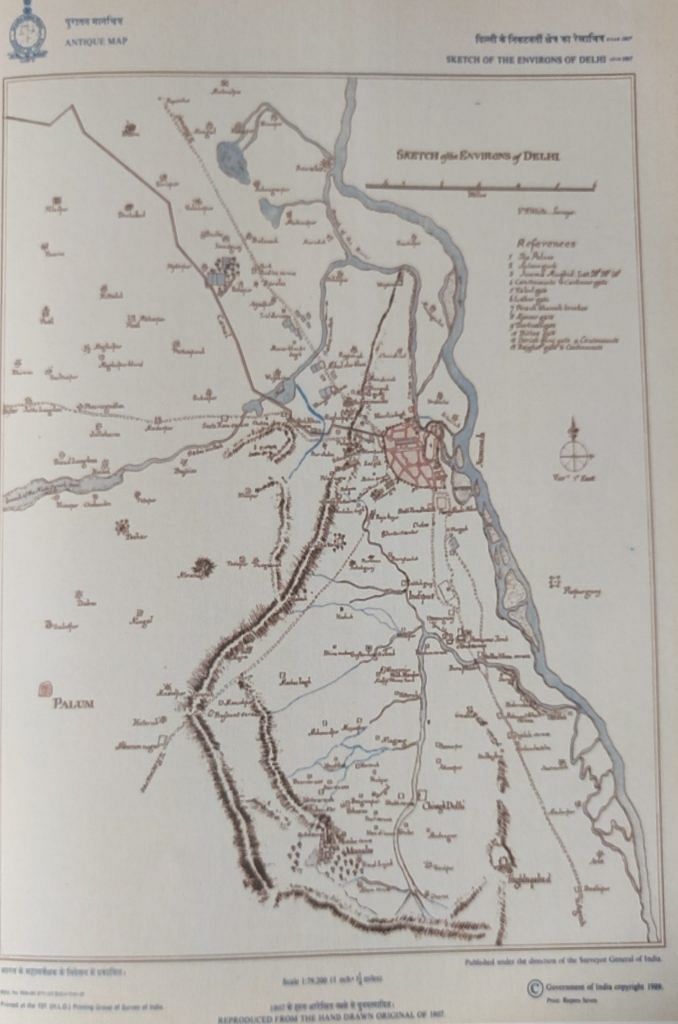

Old records indicate that the jheel was spread over 220 sq. km. Its existence was recorded as far back as 1807. It played a vital role in the agrarian economy by supporting irrigation, animal husbandry and fishing. In 1865, the government of the North-West Province started excavating an irregular channel from the eastern end of the jheel to the Yamuna. This was done to drain the jheel and create more cultivable land.

The Najafgarh jheel’s wetlands hosted innumerable migratory and resident birds, including the endangered Siberian crane, pink-headed ducks and greater flamingos. To date, wild animals and reptiles endemic to the region and several species of birds are sighted here. In addition, the jheel was a recharge source for the surrounding aquifers.

After the floods of 1964, when the Najafgarh jheel spread to 240 sq. km., widening of the irregular channel or the Sahibi river canal resulted in the drainage of the jheel. The construction of a supplementary drain in 1977 to carry excess flood discharge to the Yamuna was the last nail in the proverbial coffin, and sealed the fate of the Najafgarh jheel.

Also read: How your water bill could be key to Modi govt’s infra push for $5 trillion-economy goal

A recipe for disaster

The water of Najafgarh jheel now comprises largely of sewage from the drains of the surrounding urban sprawl, with the bulk of it being disgorged from the Badshahpur drain flowing through Gurugram. And the Sahibi river canal? It is now the Najafgarh nala, which has its own share of wastewater being emptied into it by a multitude of drains on the Delhi side. The pollutants from the jheel are leaching into the soil and contaminating the aquifers. The jheel’s ability to recharge aquifers has been severely compromised. As a result, the water woes of the residents of south-west Delhi and Gurugram have intensified because they have limited access to piped water and are heavily dependent on groundwater. Add to this, Delhi constructed an embankment on its side of the jheel after 1964, depriving its arable lands of the regular inundation and recharge cycle.

But the foremost threat is reclamation of land in the Najafgarh jheel for building purposes. There is rampant construction in the Najafgarh basin in contravention to current environmental norms. It poses a threat to life and property apart from destroying a fragile ecosystem. In fact, the recent spell of rain in August resulted in seepage and flooding in the basement of several residential colonies near the jheel in Gurugram. Sold as prime waterfront properties, the developers invariably omit mentioning that their tall concrete structures sit atop soft wetland soil with near-empty aquifers underneath. This, coupled with a high-intensity earthquake — the area is a seismic zone — could be a sure recipe for disaster.

Also read: Want to save Jaipur and its 2,300-yr-old mummy? Unclog the drains

Whose lake is it anyway?

Not only land tussles and encroachment, the jheel is also locked in several legal tussles.

The Najafgarh jheel falls under the purview of several government bodies. While the NCT (National Capital Territory) government has earmarked Najafgarh jheel in its 2021 Master Plan, no work has been done to demarcate the area of the jheel in Haryana.

Concerned about the dismal state of the jheel, the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) had filed a petition with the National Green Tribunal (NGT) in 2014 drawing attention to its imminent extinction owing to human apathy. It further said that unless the NGT intervened, the land area of the waterbody was in danger of falling into the hands of unscrupulous real-estate dealers, and the illegal construction can be used as a fait accompli to avoid/deny the revival of the jheel. This matter was disposed of in 2017 in view of the statement issued by the Haryana government that the lake (Najafgarh jheel) in question is indeed a waterbody and it was trying to approve it officially. However, even after two years, when no steps had been initiated to notify the jheel as a wetland, the INTACH filed another petition in 2019 in the NGT.

The NGT sought a status update and action report from both the Delhi and Haryana governments. In a subsequent hearing in October 2019, Haryana filed a report saying that there was a doubt about whether the Najafgarh jheel was a private land or a wetland. This doubt was based on a 2005 revenue record. But there is a 1983 gazette notification showing the area to be a lake. To ascertain facts, the NGT sought early revenue records prior to settlement. Since then, the hearing at the NGT has been extended several times because the Haryana government has not filed its report.

The Delhi government’s position on this matter is more sympathetic. It is currently planning to rent land from the farmers on the Delhi side to the north of the embankment and inundate it. Most of the decisions in favour of environmental causes in Delhi has been due to court orders (initiated by activists and NGOs rather than mass movements) forcing the hands of the government.

Also read: Covid is barely a concern for this Delhi village on Yamuna that can be accessed only by boat

Rallying call

Taking cognisance of the apathy and lack of awareness of Delhi and Haryana residents, we created a Facebook group — called ‘Najafgarh Jheel – Countdown to Extinction or Rejuvenation?’ — to raise awareness and rally people together. So far, there have only been isolated efforts by activists and NGOs to save the jheel. The formation of the Facebook group is a fledgling yet important step to consolidate these efforts.

To paraphrase Goethe, the Najafgarh jheel’s fate resembles a fruit tree in winter. Who would think that those branches would turn green again and blossom, but we hope it, we know it… provided nobody axes the tree itself. For now, Najafgarh jheel is a lake with a glorious past but an uncertain future.

The author is a PhD scholar at Teri School of Advanced Studies working on urban water bodies. Views are personal.

Was a good read. Didn’t know that the Sahibi River is the same as the Najafgarh Jheel. I tried to find the Sahibi river on Google maps, it does show up in the pictorial form of the map but not when you change the view to Satellite view.

Request to join the group on Facebook also.

This is so detailed report about najafgarh jheel….thank you ritu for this

Not just Delhi, every corporation and town planning authorities in all the indian ciities are doing the same