In a grim year that seemed to adumbrate a global calamity, books performed their indispensable duty as facilitators of mutual comprehension, expanders of intellectual horizons, and agents of edification. The great Azerbaijani novelist Akram Aylisli once described books as our “salvation from the dirt of the outside world”. To agree with Aylisli is not to endorse isolation from the world. It is to acknowledge the value of books—if not in improving the world, then in fortifying the minds of its inhabitants.

What follows is a small, idiosyncratic selection of titles from the dozens of exceptional works I was grateful to be able to read in 2023.

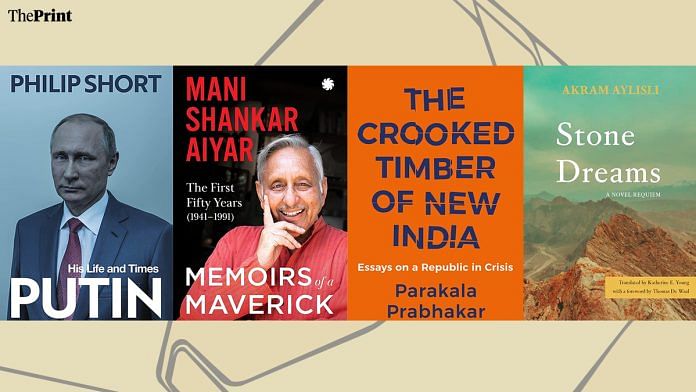

Putin: His Life and Times

by Philip Short (Vintage)

Short’s life of Russian President Vladimir Putin, published last year, is an extraordinary achievement. It does not—cannot—tell the whole story. But the story it does tell in great and nuanced detail upends attempts by establishment journalists and intransigent cold warriors in the West to cast Putin as an avatar of Adolf Hitler. Short, a colossus among British foreign correspondents, has devoted decades to studying and reporting from Russia and China. He cannot easily be brushed aside. And this outstanding biography, though far from flawless, is the product of almost a decade of unrelenting toil.

Its great merit is that it actually makes the effort to consider the world from Putin’s eyes. Virtually nothing that the Russian president has done (or is alleged to have done) beyond his nation’s frontiers is novel. Washington did it first—and did it more effectively. After the demise of the Soviet Union, Russia was treated by the United States with an admixture of pity, condescension, and scalding contempt. Putin, rising from the entrails of Soviet society to inherit power in a defeated and exhausted post-Soviet state, regarded Russia as a European nation and strove to forge warm relations with the West.

There was no reciprocity.

Instead, Washington hectored and harangued Moscow for its failings even as it presided over multiple wars that resulted in a million Iraqi deaths and the displacement of 37 million people. Western tartuffery peaked in February 2022, as so many of its politicians, patrioteers, and publications complicit in America’s wars suddenly discovered the sanctity of sovereignty. So little had changed in the century since Nehru, in a letter to Lord Lothian, shared his amazement at how Western powers “proceed on the irrefutable presumption that they are always doing good to the world and acting from the highest motives, and trouble and conflict and difficulty are caused by the obstinacy and evil-mindedness of others”. This unvarying self-unawareness helps explain why Western efforts to ostracise Russia have failed so spectacularly in the developing world.

Putin’s own view of the United States transformed radically over the years. He came to see it, Short writes, as a “deeply flawed, hypocritical, violent country” and decried it for claiming to be “shining white, clean and pure”, while treating Russia as “some kind of monster that has only just crawled out of the forest, with hooves and horns”.

None of this mitigates Putin’s conduct at home or the criminal invasion of Ukraine—a topic on which Short is, understandably, at his weakest. What it does, however, is clarify the kind of leader Putin is: an unexceptional nationalist strongman. A lot less blood would have been spilled had his puffed-up critics in the West—with their obscene record of stamping on other countries’ sovereignty, overthrowing popular governments, and propping up murderous tyrannies—spent more time talking to him than feeling good about themselves for being dogmatically opposed to him.

Memoirs of A Maverick: The First Fifty Years (1941–1991)

by Mani Shankar Aiyar (Juggernaut)

Mani Shankar Aiyar must be the sole Congress politician of his background, serving or retired, who refuses to make even the minutest intellectual concession to the ideology that drives India’s current rulers. Born in the decade in which India became independent, he is so completely committed to Nehru’s secular nationalism that he cannot abide those who have come to terms with Narendra Modi’s dominant role in the Indian republic’s unfolding story.

But before his beliefs landed him in trouble in 2017—when his description of Modi as “neech” was unjustly ascribed to some deep-seated caste prejudice and he was swiftly cast aside by his party’s craven leadership—Aiyar led one of the most interesting post-colonial lives. The memoirs he finished writing in involuntary retirement turned out to be so lengthy (Aiyar turned in a million words) that his publisher decided to split and stagger their release.

The first part of Aiyar’s memoirs—chronicling his life from 1941 to 1991, including the transition from bureaucracy to popular politics—is nearly 400 pages long. A companion volume, The Rajiv I Knew, And Why He Was India’s Most Misunderstood Prime Minister, is scheduled to be published in January. The concluding portion of his life’s story is expected in the second half of 2024.

Given the richness of Aiyar’s life, Memoirs is frustratingly episodic—a collage of disconnected yet controlled recollections of school, college, and university that sheds scarcely any light on the inner life of one of India’s most unapologetically secular politicians. The book livens up only after the arrival of Rajiv Gandhi. And what is remarkable here is Aiyar’s willingness to castigate his friend and beau ideal for his “egregious” mimicry “of the saffron forces and appeasement of the majority community”. The Rajiv government’s handling of the Babri dispute, Aiyar observes, was “cynical, unprincipled, opportunistic”.

Unlike his previous works—Pakistan Papers, In Rajiv’s Footsteps, and Confessions of a Secular Fundamentalist—Memoirs of A Maverick is a Delhi book, overloaded with Delhi trivia, and afflicted with the condition VS Naipaul called “looking without seeing”. One of the most brilliant alumni of the Foreign Service shares no insight into the world historical events—the fall of the Shah of Iran, the collapse of Yugoslavia, the end of the USSR—that unfolded in the period covered in this volume.

Even the birth of Bangladesh—which was preceded by the worst atrocities ever perpetrated against a predominantly Muslim population by a state invented explicitly to safeguard Muslims from non-Muslims—gets three paltry pages. Perhaps it is unfair to fault a book for what it is not. But Aiyar, who spent a career seeing history unroll from the front rows, does no more than take a perfunctory look at it for the benefit of his readers.

All of this is tragic because Aiyar, besides being a man of unyielding courage and principle, is perhaps the last pan-Indian secularist and non-aligned internationalist of his kind. Throughout his career, his revulsion for VD Savarkar was matched only by his contempt for MA Jinnah, and he was never afraid to condemn Pakistan and Hindutva as two sides of the same sectarian coin. Aiyar has softened in retirement. The secularist who in Pakistan Papers declared that “Pakistan can become a stable, military-free democracy only by dissolving Pakistan” now reprimands Indians for not sufficiently engaging the quasi theocracy next door that functions as a model for the Hindu Rashtra our overlords yearn to raise here.

And yet—and yet. Despite its defects, this bowdlerised self-memorialisation of the life and career of one of India’s most distinguished and patriotic citizens is made valuable by the mere fact of its existence. There is sufficient material here for serious scholars of India. And Aiyar, one of India’s most polished orators, is a superlative writer. His remembrances are suffused with genuine feeling. The story of the assassination of Rajiv—“my friend, patron, and mentor”—is told especially poignantly.

Aiyar ends the book with a pensive coda that radiates resignation rather than resentment: “my life in politics rose in spurts to its highs and then spluttered out to the point where I find myself sidelined by Rajiv Gandhi’s heirs.” A Jewish midrash says that those who are kind to the cruel will ultimately be cruel to the kind. A party that furthers the careers of such vacuous sciolists as Jairam Ramesh—who has never in his life faced the electorate—naturally cannot long tolerate a man as learned and righteous as Aiyar.

All of us who admire Aiyar can only pray for a biographer who can do justice to a life that is evidently too maverick for autobiography.

The Crooked Timber of New India: Essays on a Republic in Crisis

by Parakala Prabhakar (Speaking Tiger)

In his foreword to this book, Sanjaya Baru lists its author’s many professions: “An economist, a public policy professional, a corporate consultant, a public opinion pollster, a political activist and analyst, a writer, a Telugu litterateur, a scholar.” Parakala Prabhakar is also a person of integrity.

At the summit of the hysteria to sunder Telugu-speaking Indians into two states, Prabhakar put together a pamphlet called Refuting an Agitation: 101 Lies and Dubious Arguments of Telangana Separatists. It was so simple and yet so forceful that Prabhakar was savagely attacked by the agitators for Telangana. Those behind the enterprise pitted Indian against Indian and pledged to convert Telangana into a vehicle for social justice after purging it of such apparent “outsiders” as Prabhakar. Once Andhra Pradesh was divided, they spawned a dynasty and treated Telangana as a cash machine.

In this luminous collection of essays, Prabhakar exposes the charlatanry at the heart of an even more crooked enterprise: “New India”. Modi, lest we forget, waged his first campaign for high office on the promise of development and anti-corruption. And after his election, as Prabhakar reminds us, he continued to cast himself as a consensus builder who pleaded with Indians to engage in the “experiment” of “peace, unity, goodwill, and brotherhood.” That Modi, too good to be true, “has now disappeared”, Prabhakar writes. What follows is a diligent deconstruction of the lasting damage to India—to the prospects of unity, goodwill, and brotherhood in India—over the past decade.

Prabhakar doesn’t blame this government alone for this dire state of affairs, nor does he pretend that Modi is an aberration. “The most effective challenge to the [Hindu nationalist] project should have come from political parties ideologically opposed to the BJP and its Parivar,” he writes. “But they have failed us—a long, consistent failure of vision, strategy and energy.”

Stone Dreams

by Akram Aylisli; translated by Katherine E Young (Academic Studies Press)

Akram Aylisli is the greatest living Azerbaijani writer. In early 2000s, he was given a seat in parliament and garlanded with state honours, prizes, and medals. But unbeknown to everyone, he was quietly working on a novella that would end his career, make him persona non grata in his country, and reduce him to the status of a prisoner in his home.

Stone Dreams, first published in 2012 in Moscow, is set in Aylis, the village in Nakhichevan where Aylisli grew up listening to his mother’s stories of the persecution of the native Armenians by the Turks during World War I. Aylisli’s home was an exception: the Armenian Genocide was a taboo subject which nobody addressed in public.

Sadai Sadygly, the hero of Stone Dreams, ends up in a hospital after being brutally beaten for attempting to protect an Armenian from the mob. There, in his dazed state, he remembers his past and the past of his land and its people, and is seized by the “desire to set out for Echmiadzin”—the seat of Armenian Christianity—“to accept Christianity with the blessing of the Catholicos himself, to remain there forever as a monk, and beseech God to forgive Muslims for the evil they’d done to the Armenians”.

Aylisli has no regrets. As he told Thomas de Waal last year, “By the publication of Dreams I saved many Armenians from hatred towards Azerbaijanis.” This is true. But the readers who could perhaps profit most from Stone Dreams are in Azerbaijan, and Aylisli’s most poignant work appears fated to be withheld from them for now.

Kapil Komireddi is the author of ‘Malevolent Republic: A Short History of the New India’, which will be published in a revised and updated edition next month. Follow him on Telegram and Twitter. The views expressed above are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)