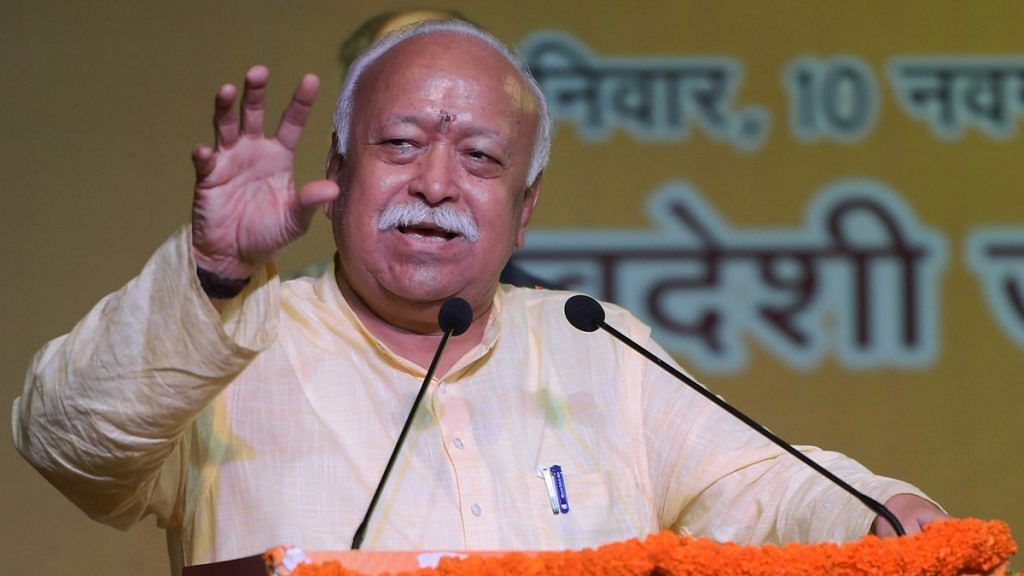

Last week, RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat once again kicked a storm by calling for a ‘debate’ on the issue of reservation. In 2015, Bhagwat had asked for a review of the system that grants reservation in government jobs and education to Dalits, tribals and other backward classes. The only difference this time was his attempt to disguise his intention by asking for the dialogue to be held “in a harmonious atmosphere” – those in favour and against caste-based quota should hear each other out.

Those opposed to reservation often make similar demands and call for an end to caste-based reservation. They repeat the same myths that the proponents of the policy have busted over the years, highlighting why reservation for Dalits, tribals and other backward classes (OBCs) must continue – historical systemic injustices, social discrimination, daily atrocities over caste, and lack of representation in education and employment. Even the Supreme Court of India has started demolishing these myths.

Yet there is one point that both sides regularly miss: Reservation provided to marginalised social groups is India’s soft power in the global community.

Also read: Until 2016, India was on course to break into soft power group of 30 nations. Then it fell

India’s affirmative action a model for others

Reservations or the quotas are India’s model of affirmative action policies. In the contemporary global discourse on rights framework, where affirmative action is considered as an “international human rights dialogue”, India’s model of affirmative action, entrenched into its Constitution since 1950, is considered to be the world’s oldest. The discourse on affirmative action in the United States came in the 1960s and in South Africa in the 1990s. As other nations engaged with similar affirmative action policies, targeted at groups that have historically been oppressed in their nations, policymakers and scholars have often looked to India for lessons.

The positive impact of India’s constitutional model has been recognised by the popular judge of the US Supreme Court, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in the following words: “India … has undertaken affirmative action initiatives in regard to disfavored castes that are both older and more extensive than any program ventured in the United States”. She refers to reservations provided to marginalised social groups as Indian Constitution’s bold announcement of “a commitment to affirmative action”.

In this background, Justice Ginsburg calls for a comparative analysis for interpreting the US Constitution: “In the area of human rights, experience in one nation or region may inspire or inform other nations or regions… We are the losers if we neglect what others can tell us about endeavors to eradicate bias against women, minorities, and other disadvantaged groups”.

Also read: Subramanian Swamy was right. Modi’s lateral entry plan will make reservations irrelevant

Taking pride in quota

Reservations have also made the world’s largest democracy inclusive. While the world’s oldest democracy, the US, is still facing the challenges of equal voting rights and a possible dilution of votes of racial minorities, India’s political reservation ensures that Dalits and tribals, who constitute more than 250 million of the country’s population, are duly represented in Parliament and state assemblies. This has strengthened India’s democratic credentials before the world.

American journalist Kenneth Cooper once wrote that the United States can learn from younger democracies such as that of India, when it comes to making amends for historical injustices. Cooper argued the founders of Indian democracy made a lasting commitment to social equality.

Moreover, in order to push for structural reforms in other countries, the Indian State has itself officially taken pride over its affirmative action programme before the global community. Representing India at the ‘World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance’ in 2001, Omar Abdullah (then-minister of state for external affairs in the Atal Bihari Vajpayee-led government) had said: “The Constitution pioneered affirmative action programmes for … the uplift of the members of the historically disadvantaged castes. We are proud of the positive difference these measures have made… We are determined to continue this national endeavour”. He had added: “The Conference should also encourage countries to introduce affirmative action in respect of disadvantaged segments of their populations.”

Also read: Supreme Court just destroyed the ‘merit’ argument upper castes use to oppose reservations

Caste, not quota, needs to go

However, it must be noted that while efforts, through affirmative action, have been made to bring Dalits and tribals into the mainstream, a simultaneous dilution of these attempts continue to take place in the form of everyday discrimination and through incidents of atrocities against members of these communities.

Barack Obama, the US’ first African-American president, had once remarked in an interview, “You have countries like India that have tried to help untouchables, with essentially affirmative-action programs, but it hasn’t fundamentally changed the structure of their societies”.

Nearly all discussions, or calls for one, invariably end up on the issue of reservation. What must be discussed instead is why this structure of social discrimination against Dalits and tribals still exist in India in the 21st century and how it can be destroyed.

For India to become a guiding light of justice for the world, its citizens must start working towards building fraternity and demolishing prejudices and discrimination against the marginalised communities.

As for reservations, it is time our leaders and diplomats began to openly flaunt our constitutionally guaranteed system just the same way that yoga, Gandhi, Buddha, Bollywood, and the country’s diverse democracy are projected as India’s soft power abroad. Those who oppose reservation policies or want to review them must understand the same.

The author is LLM’19 postgraduate from Harvard Law School. Views are personal.