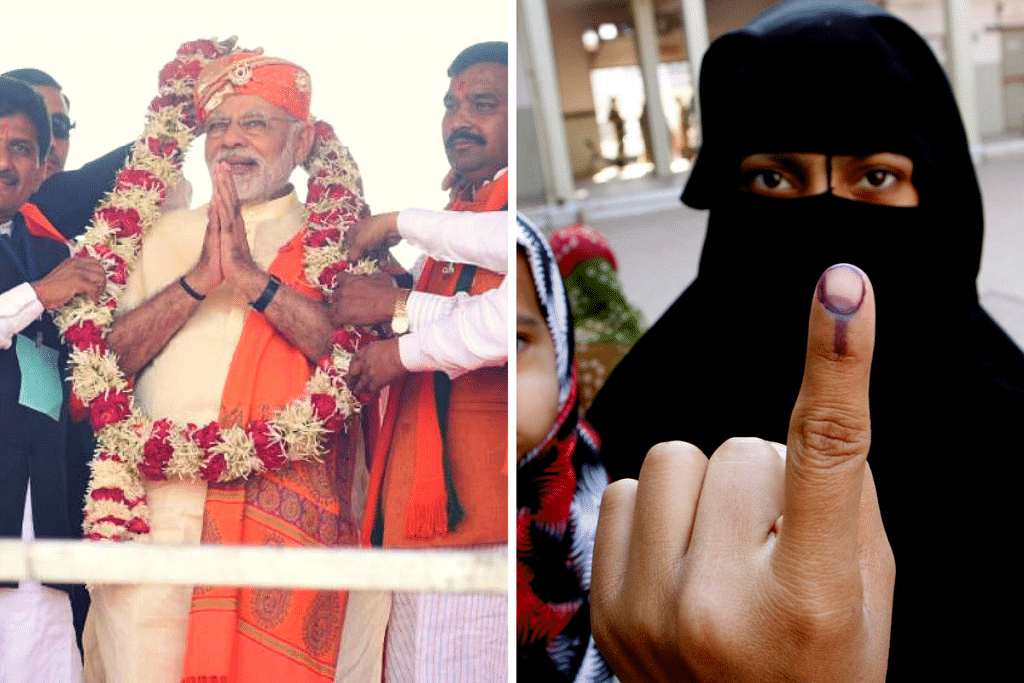

The implications of a prime minister polarising a state election on religious lines is way more serious and far-reaching. But Modi seems ready to risk the fallout.

However objectionable you may find the latest Mani Shankar Aiyar/Pakistan/Ahmed Patel twist in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s campaign in Gujarat, don’t be surprised. No other state in India harbours suspicion of the Muslim and the paranoia for Pakistan you see in Gujarat.

Nobody understands it better than Modi. As the crunch moment arrives, he is only hitting his fail-safe button.

I have tried analysing this phenomenon, unique to Gujarat, in the past. I have never been able to do so convincingly. I have experienced it first-hand though, and to my cost.

My first visit to Ahmedabad as a reporter was in 1985 when the Mandal Commission Report (which had just hit the headlines) caused early riots in Bhopal and Ahmedabad. I was working on a cover story on Mandal and reservations. By the time I reached curfew-bound Ahmedabad, the riots had taken a communal colour. Mandal and caste had been forgotten.

The rule in Gujarat, I was then told by a top cop I knew from his Intelligence Bureau posting in the northeast was: every riot, every tension, anything that is contentious, ultimately takes a Hindu-Muslim colour here. This was much before the rise of the BJP here. Nobody knew Narendra Modi then.

In 1992, I visited Gujarat often as we planned to launch the Gujarati edition of India Today that year. Sometimes I landed in Ahmedabad in the morning and carried on to Mumbai later in the evening. On one of these visits, I carried a bottle of whiskey in my bag. True confession: I had some friends coming over later that evening in Mumbai and didn’t want to pay hotel prices for alcohol. Security caught me on my way out at the airport.

I pleaded that I had only arrived for a few hours that morning, that the bottle was still sealed and I had neither broken, nor had any intention of breaking the prohibition law in Gujarat. The policeman wasn’t impressed. He would not charge me, but confiscated the bottle.

What was the point doing it on my way out, I was leaving and couldn’t be drinking it on Gujarat’s soil, I argued again and failed. And then I made a blunder in exasperation. I said, arrey bhai, I travel to Pakistan often, bootleg duty-free liquor for my friends, and no airport stops me once I tell them I am Indian, a journalist and a non-Muslim. He went all red in the face: do you even know what all happens in Pakistan? How dare you even mention Pakistan here?

I grudgingly conceded the argument and my bottle of Black Label. This was the summer of 1992, several months before the Babri Masjid demolition and the communal riots.

Later in the year, on the first day of Navratri, we launched the Gujarati edition of India Today magazine. I was then, besides being Senior Editor at the English magazine, also publisher of its international and several language editions. Entry into the Gujarati magazine market was exciting as it was my first launch. Incidentally, that is when I first met Narendra Modi, then a party worker in a modest one-room home. We were introduced by Sheela Bhatt, then editor-designate of the Gujarati edition of India Today.

The edition did brilliantly within weeks and we were closing in on the one-lakh mark. Then we were barely in our sixth fortnightly issue and the Babri demolition happened. We took a firm, secular and constitutional stand on it. Our English cover headline was, “Nation’s Shame”. Gujarati, was an exact translation, “shame” becoming “kalank”.

The marketing head, Deepak Shourie, warned us. He said Gujaratis would never accept this. We stuck to our editorial stand and decided we were not going to finesse it to suit a market.

He was proven right. The issue led to a storm of protests. These were pre-internet days, but my desk was flooded with letters calling us “Pakistan Today” and “Islam Today” etc. Within the following month, the sales had fallen by 75 per cent. The edition never recovered and had to be eventually shut down, after a long period of resuscitation failed. This, mind you, was years before the rise of Modi. Congress was still in power in Gujarat, so please do not blame Modi or Moditva. This was the Gujarati public opinion.

Is there something about Gujaratis that makes them particularly angry with Muslims? In a 2012 pan-India opinion poll conducted by NDTV, one of the questions was whether India should have better relations with Pakistan. In Punjab, 72 per cent people said yes, and in Haryana, 80 per cent. In Rajasthan the number was 42. All three are states with a soldiering tradition and two share long borders with Pakistan.

And in Gujarat? It was just 30, the lowest in the country. What is it that makes Gujarat our angriest border state?

I have never been able to answer this. Some of my scholarly Gujarati friends point to the long history of Muslim invasions and serial sackings of the Somnath Temple. Maybe that’s why Alauddin Khilji has such an angry echo here. The Padmavati controversy, in that sense, was well-timed for the BJP.

Some even noted that while Gujarat never saw much fighting despite being a border state, it was witness to two serious setbacks.

The first, the Kutch conflict of early 1965, in which India performed poorly (The Monsoon War, by Capt. Amarinder Singh and Lt. Gen. Tajinder Singh Shergill) and had to agree to a humiliating ceasefire and international arbitration (territory thus ceded was recaptured in 1971); and second, the tragic shooting down of the state government’s official Dakota, carrying then chief minister Balwant Rai Mehta, by a Pakistani Sabre during the September 1965 war. Mehta, very popular then, is the only public figure to lose his life in a conflict in our independent history. There must be something to these, but they still look distant and don’t conclusively explain the Gujarati anger.

These are indicators and while we may debate the “why” of it, that the Gujarati view on Islam and Pakistan is unique for any state in India, is a reality. The same editorial view and headline that sank our Gujarati edition post-Ayodhya had made the sales of our much bigger Hindi edition zoom in the heartland.

The communal riots of 2002 weren’t the first in Gujarat. But these were the first where Gujaratis were convinced—and with good reason—that finally the Muslims were “taught a lesson”. That belief is central to Narendra Modi’s political capital in Gujarat.

In each campaign since then, he cues the voters in that direction. It was the taunts of “Mian Musharraf” in 2002, “criminals keep infiltrating across the border in Assam, but no Aaliya-Maaliya-Jamaaliya can dare to come into Gujarat” in 2007. By 2012, he was rebranding himself for a national role and there was no challenge from the Congress, so he avoided going there and stuck to development.

He sees more of a challenge this time, given 22 years of incumbency, his absence, a divided state unit, two non-entity successors, a rejuvenated Congress with three young caste leaders as allies. The implications of him returning to the “basics” is way more serious and far-reaching than as chief minister of a medium-sized Indian state. But he knows what is at stake in Gujarat and won’t leave anything to chance. He wants to win at any cost and is willing to risk the fallout. Whether Gujarat still responds with the same Muslims=Pakistan=mortal enemy belief, will determine the numbers on 18 December.