The commodification of women by influential men has a long, tragic history in India. From practically the beginning of urban settlements in the 5th century BCE, literary sources mention the presence of enslaved women in the country. And well into the 19th century, until British colonial laws were enforced across South Asia, a vast body of evidence indicates that elites participated in the trafficking of women. Contemporary attitudes often have deep historical roots—deeper than we might think.

Bodyguards and goddesses

One of the earliest mentions of enslaved women comes from the Antagada-Dasao, an early Jain text dating to around the 5th century BCE, when kingdoms were emerging across the Gangetic Plains. It depicts a prince as being attended to by Persian and Greek women, as well as many local women. India had no direct links with Greece at the time: the presence of Greek women in such an early text may indicate they were slaves trafficked through Persia, at the time the world’s mightiest empire.

Adding heft to this theory are roughly contemporary claims by the Greek historian Herodotus. As historian Kathryn A Hain points out in her paper, The Prestige Makers: Greek Slave Women in Ancient India, Herodotus claims that ravaging Persian raids captured Greek women for slavery and sale.

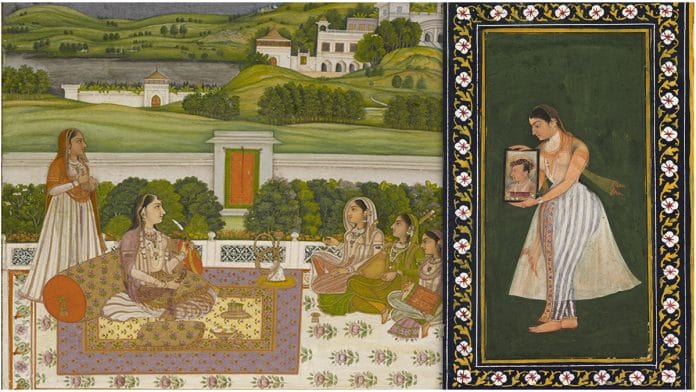

In subsequent centuries, early Indian rulers prided themselves on having large numbers of women attendants, an attitude that was fairly commonplace in the premodern world. Having foreign women in court demonstrated a king’s reach and wealth to his rivals and subjects. Foreign women could also fill roles that Indian women were socially or culturally restricted from, such as bodyguard duty.

The Mauryan kings (4th century BCE), for example, were protected by bow-wielding Greek women, who, as Hain points out, might even protect him from his own queens. A large number of Sanskrit sources, well into the 3rd century CE, mention “yavanis”, women from the Mediterranean, in this role. But they are also described, flushed with imported Western wine, as courtesans and sex workers. Some women were also trafficked from the African coast, and referred to as “barbari”. Roman historians and trade documents support these literary claims, indicating that enslaved women taken to India brought considerable tariff income.

India’s trading contacts with the Mediterranean waned somewhat in the 4th century CE. At the same time, a new model of Indian kingship was emerging—intertwining virility, martial success, and control over women. Over the next thousand years, Indian kings commissioned Sanskrit-language eulogies declaring their success in all these fields. Martial conquest was often presented as a sexual conquest, with the goddesses of Fortune, Earth and the four directions represented as beautiful women. For example, the 7th-century Chalukya king, Vikramaditya I, attacked the city of Kanchi to his south. Then, in the overblown language of his time, he claimed to have “joyfully enjoyed the lady of the southern quarters after subduing her through force and taking possession of Kanchi, her girdle”. A little more than a century later, King Krishna I of the Rashtrakuta Empire defeated the Chalukya family, and claimed in turn that he “In the battlefield which proved a place of choice marriage… [he] forcibly wrested away the fortune of the Chalukya family.” Such attitudes were prevalent across South Asia. Even the famous Chola dynasty, for example, mentioned the mutilation and capture of rival queens, and their absorption into palace service retinues.

Also read: South India’s Jain goddesses you haven’t heard of: Establishers of dynasties, fierce protectors

Medieval slave trade

Violence was not confined to elite women, either. Medieval hero stones, which marked valiant deaths in villages, frequently record that women were abducted or about to be abducted, until rescued by a now-dead hero. This must indicate that many more women were abducted.

The situation grew worse in the late medieval period, when Sultanates across Northern India connected the Gangetic Plains to Persia and Central Asia, which relied on slave labour. From Sultans to minor landlords, many men participated in the trafficking of enslaved people. A 13th-century Sanskrit text from Gujarat, the Lekhapaddhati, provides examples of a certain “Rāṇā Pratap Siṁgha” and “Śrī Vīradhavaladeva, a rājaputra”, who captured sixteen-year-old girls in raids and then sold them into lives of cruel oppression.

Multiple texts attest to the presence of slave markets in Delhi and other major cities. Even as far as Syria and Egypt, contemporaries wrote approvingly of enslaved Indian women, both Hindu and Muslim. The number of trades is difficult to verify. As historian Shadab Bano writes in India’s Overland Slave-Trade in the Medieval Period, 14th century travellers thought the name of the Hindu Kush mountains was derived from the death of thousands of enslaved Indians who passed through them. It’s possible that this is an oral legend, but it still indicates the very real scale of the slave trade. Many of these people were poor and landless, captured in wars and raids before being packed off to miserable deaths in the cold.

Even as Indian women were sold off, Central Asian, Turkic, and Caucasian women were purchased. Many late medieval kings had foreign ladies in their palaces as palanquin-bearers and bodyguards. These palace establishments were also home to hundreds of Indian slave women.

It was only in the 16th century that the Mughal emperor Akbar finally banned slave trade, but this still didn’t stop the practice. Indeed, as professor Bano points out in another paper, Women Slaves in Medieval India, there is documentary evidence that some Mughal officials captured women in raids and even used them to pay their soldiers’ salaries. And as late as the 19th century, British officers such as Francis Buchanan and John Malcolm found that zamindars and Rajputs in Central and East India still owned large numbers of enslaved women.

Also read: Hema Committee is a start. How many reports, careers, lives before we see real change?

Even queens weren’t safe

In recent years, medieval Indian queens have at last begun to get their due. Mughal historian Ruby Lal, in her biography of Nur Jahan, writes that this 17th-century empress freed slave women in her palace and made arrangements to support working-class women.

We’ve also seen, in earlier editions of Thinking Medieval, that queens could rule kingdoms and order war. But at the same time, if the men of their families were defeated, the bodies of the queens were on the line, targeted by enemies.

Though some women, thanks to their birth and wealth, were able to wield power, the majority could not. In the absence of constitutional protocols and an understanding that all people are equal, premodern women were frequently subject to violence, objectification, and slavery. Even royal status was only a partial remedy. We cannot talk about queens without accepting that premodern Indian societies were difficult places for women, and this laid the base for our contemporary attitudes.

Where does this leave us today? I do not want to suggest that misogyny is so ingrained in our past that we cannot overcome it. After all, premodern Indians existed in a world where the oppression of women was routine. Yet many societies that India once traded with have created safe, respectful working environments for women. Europe, once home to the Roman Empire—an economy based almost entirely on slave labour—consistently ranks high on equality and safety indicators. There is still a long way to go, but acknowledging our troubled history is a necessary first step.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

Your article is a bogus anti India and anti Hindu propaganda

Stop maligning Indian history, the interpretation is purely based on how you interpret women. Women were treated with utmost respect, it’s only Mughals came and started dis respecting woman as it was allowed in their culture. Your are painting the picture otherwise.shame on you

He is an anti India and an anti Hindu leftist propagandist, what can you expect from him, you can never expect true history from him.

The current state of women is much better than it was when we had the highest GDP in the world. Wealth is nothing without respect for human dignity.