The jet landed at a desert airbase an hour’s drive from Mecca, loaded with bulletproof jackets, gas masks, and hundreds of kilograms of the chemical weapon dichlorobenzylidene malononitrile. For celebration—or, who knows, for the consolation of failure—the cargo included a case of 1974 Sauvignon, to mark the year France’s élite police tactical unit—the Groupe d’intervention de la Gendarmerie Nationale, had gone into operation. A bottle broke open when the cargo was being unloaded; the Saudi Arabian officers chose to ignore the famous aromas of cat-pee and fresh-cut grass rising from the tarmac.

French defence minister Yvon Bourges had thought it would be simple: “You have to eject a couple of imbeciles from some grotto,” he told the special forces officers. “Child’s play.”

Almost five decades have passed since the uprising inside the heart of Islam in 1979—superbly recorded by the journalist Yaroslav Trofimov in a riveting book—when a few hundred followers of the Al-Jamaa Al-Salafiyya Al-Muhtasiba almost succeeded in seizing the mosque at Mecca, and bringing down the Saudi monarchy.

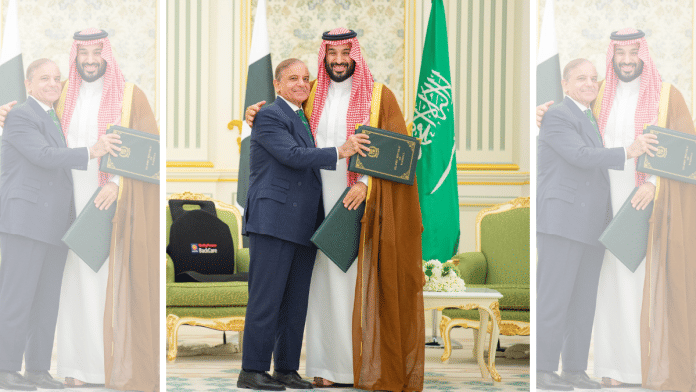

The mutual-defence agreement signed between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia last week, as political scientist Ayesha Siddiqa has pointed out, is about many things: Deterring Iran from acquiring or using nuclear weapons; hedging against American withdrawal from the region, and protecting the kingdom’s borders against countries like Yemen.

There’s a simpler truth, though, that also stalks the mind of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman al-Saud: Like they did in 1979, religious conservatives have been digging in against efforts to introduce a more cosmopolitan culture to the kingdom.

Last week, the regime was forced to shut down several mixed-gender music clubs in Riyadh and Jeddah, and a new unit was set up at the Interior Ministry to enforce religiously-sanctioned behaviour. This, many fear, reintroduces the feared Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, the religious police whose powers were curtailed in 2016.

Figures in clerical circles are also stepping up the pressure. The Indonesian-origin Sheikh Assim Al-Hakim—known to his young followers as “Sheikh Awesome,” writes scholar James Dorsey—is one of a ‘circle of clerics’ discreetly challenging Prince Salman’s cultural policies, especially on gender segregation. Less cautious clerics—like Sheikh Badr Al-Meshari and Salah al-Talib—are in prison, while Muhammad al-Ghamdi faces execution for advocating for the right of clerics to advocate their views.

Even though the media in the West sometimes gives the impression that young Saudis overwhelmingly back Prince Salman’s efforts at Westernisation, some data suggest there is a deep pool of resentment. Though half of the respondents wanted a “more modern” interpretation of Islam, support for interfaith tolerance lagged far behind. Another 2025 study by Gareth Butler and Alhussein Hothan showed that many young people were suspicious of public music concerts.

A rebellion in the making

Like all processes of deep economic change, King Faisal bin Abdulaziz Al-Saud’s efforts to modernise his kingdom created winners and left behind communities. The country’s Bedouin tribal communities watched, bewildered and increasingly angry, as the country’s élite wallowed in oil wealth. From the mid-1960s, a small group of pietists began to gather in Medina’s markets, destroying mannequins and ripping up photographs. This group’s actions drew the attention of the police, but also gained the protection of the powerful cleric Abd al-Aziz Ibn Baz, the vice-chancellor of the Islamic University of Medina.

Early in the 1970s, the Ikhwan, or brothers—as the members of the Al-Jama’a al-Salafiyya al-Muhtasiba, or JSM, called themselves—had set themselves up in a two-storey building in one of Medina’s poorest and conservative neighbourhoods, al-Hara al-Sharqiyya in Medina.

The JSM’s membership and sources of scholarship were remarkably eclectic. The group, scholars Thomas Hegghammer and Stephane Lacroix have written, recruited from among Saudis, Egyptians, and even African-Americans, some with backgrounds in the Muslim Brotherhoods and others in the Tablighi Jama’at. There is evidence, from the work of the Pakistani journalist Nadeem Paracha, that there was at least one Pakistani member in the group.

The Pakistani cleric Badiuddin Shah Al-Rashidi Al-Sindhi, a Jamaat Ahl-e-Hadith follower who at the time taught in Saudi Arabia, was a prominent influence. The Syrian Muhammad Nasir Al-Din Al-Albani, from a similar ideological lineage, was also popular among the JSM’s Ikhwan.

Late in 1973, the JSM was joined by Juhayman Ibn Muhammad Ibn Sayf Al-Otaybi, who arrived in Mecca after completing more than two decades of service in the country’s National Guard. The son of a Bedouin family, which had fought in the Ikhwan revolts against the monarchy in 1927-1930—and eventually crushed by Royal Air Force combat aircraft—Juhayman believed the Kingdom’s legitimacy rested on coercion, not true religious authority. Tensions between the crown and the Bedouin flared in 1969, over a law allowing the takeover of tribal lands. As the relationship with the crown frayed, Juhayman was forced to flee into the desert, beginning a life of peripatetic wandering from 1976 to 1979.

Also read: Pakistan strategic pact with Saudi Arabia is really about Iran. And blessed by US

The war at the Kaaba

Few credible accounts exist of just what happened in November 1979, but it is clear the JSM had prepared for a decisive confrontation with the state. Large numbers of weapons had been smuggled in from Yemen in the preceding months, and soldiers of both the National Guard and regular army were recruited to join the rebellion. The group, historian Pascal Ménoret has written, became increasingly mired in millenarian fantasies, insisting that one of their number, Muhammad Bin Abd Allah Al-Qahtani, was the Mehdi, or Messiah, who was prophesied to appear at the end of time.

The seizure of the mosque on 20 December 1979 went almost without a hitch: Fearful, and paralysed by the sheer magnitude of what they were witnessing, the Saudi royal élite dithered.

Events soon began to spiral out of control. Local police and the National Guard, unable to withstand the accurate fire from the rebels, soon fled the area. The Saudi Sixth Paratroop Battalion, charged with proceeding through the opulent marbled corridor between the Marwa and Safa hills, was mauled by snipers and lost much of its leadership. The Saudis tried again, using M113 armoured personnel carriers, only to be set alight in a lethal barrage of Molotov cocktails.

Fearing the public relations consequences, the Saudi monarchy rejected offers of help from other Arab states. Their friends, though, proved less than useful. CIA-provided tear gas penetrated the masks worn by the bearded Saudi soldiers, but the rebels managed to protect themselves with water-soaked rags. The cisterns, caves, and storage rooms under the mosque seemed impenetrable.

To make things worse, the crisis spread beyond Mecca. In Islamabad, students of the Jamaat-e-Islami burned down the United States embassy, following rumours that the United States had stormed Mecca. General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq’s military stood by as the attack proceeded, refusing to intervene. There was another attack on a United States mission in Libya, as well as violence in Kolkata and Hyderabad.

Meanwhile, Saudi troops machine-gunned protestors in the Shia-majority Qatif on 23 November. Though the protests had nothing to do with the events in Mecca, the pressures on the Saudi state had reached a crisis point. There is no account of how many people died: Estimates range between a few hundred and several thousand.

Also read: Is India recalibrating Russian oil import strategy? Saudi Arabia discount offer is key

The curtain falls

The three French special forces officers dispatched to Mecca discovered a broken, demoralised officer corps, lacking the elementary skills needed to flush the remaining rebels out of the catacombs. The plan, developed by Captain Paul Barril, was to drill holes into the basement, then drop the chemical gas, and use grenades to disperse it. As the gas stunned the defenders, Saudi troops would advance up the corridor. Eighteen hours after this final assault began, the catacombs were finally cleared, and Juhayman had been made prisoner.

Large parts of the story remain a mystery to this day. In his own accounts, Trofimov notes, Barril claims he entered the mosque, barred to non-Muslims, to supervise operations, possibly after a quick-and-dirty conversion to Islam. There are other accounts, though, that dispute this.

The consequences of the fighting were enormous. The clerics agreed to ensure Khalid bin Abdulaziz Al-Saud—but only if the cultural liberalisation ushered in under King Faisal was rolled back. There would be no more women on TV, no movies with romantic scenes, and most certainly no quiet tolerance of alcohol. A share of the Kingdom’s oil revenues, moreover, would now be committed to spreading the clerics’ dystopic Islam worldwide, giving them unprecedented power and influence.

Later, from 1982, some 18,000 Pakistani soldiers began to serve in the Kingdom, designated the second Khalid bin Walid Armoured Brigade and subject to Saudi law and under the command of its monarchy. The relationship was not a new one. From the mid-1960s, scholars Marvin Weinbaum and Abdullah Khurram have written that Pakistan Air Force pilots occasionally flew Saudi jets, battling Yemeni incursions. An armoured battalion was stationed at Tabuk. After 1982, this grew into a regime-protection mission, made up of three tank battalions, a mechanised infantry battalion, and an air defence battalion.

The Brigade was finally withdrawn in 1990, though it returned briefly to defend the Kingdom’s borders in the First Gulf War. Likely, the new agreement will see it back—protecting the Kingdom from Saudi jihadists who have fought elsewhere in the region, insurgents in Yemen, and, most importantly, Saudis themselves.

Praveen Swami is contributing editor at ThePrint. His X handle is @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)

I do not understand why a King Saudi Arabia is begging for a Nuclear Umbrella from a beggar country like Pakistan. Pakistan is a Rogue Nation with several terrorists groups being trained by the Pakistan Army/ ISI. In fact their Nuclear arsenal is kept in a leaky box. The King of Saudi Arabia appears also to be senseless & lunatic person.