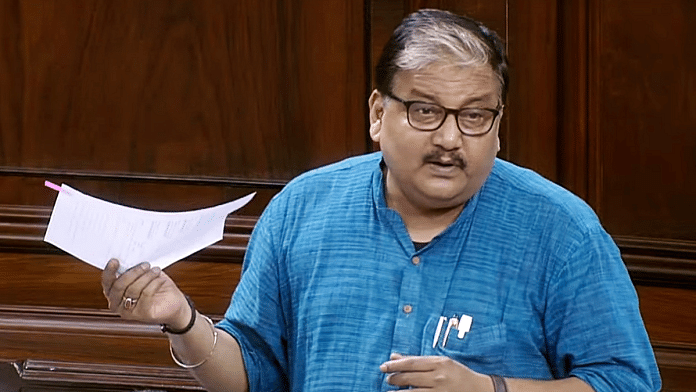

Rashtriya Janata Dal MP Manoj Jha’s recitation of Om Prakash Valmiki’s poignant poem, Thakur ka Kuan, during the recently concluded special session of Parliament has ignited debate. While the poem’s literary brilliance is beyond reproach, the context in which it was presented raises significant concerns, calling for a deeper investigation of its implications.

Valmiki’s poem is a tapestry of nuances and demands a discerning ear. The composition was inspired by a story of the same name by Hindi literary great Munshi Premchand. Premchand set his tale in early 20th century Awadh, where Thakurs formed the dominant caste – a fact one must know before proceeding to read the story or the poem.

Valmiki’s Thakur ka Kuan starts like this: “Chulha mitti ka, mitti taalaab ki, taalaab Thakur ka. Bhookh roti ki, roti baajre ki, baajra khet ka, khet Thakur ka (The oven is made of mud, the mud is from the pond, and the pond belongs to the Thakur. We are hungry for bread; the bread is made of millets, the millets come from the field, and the field belongs to the Thakur).”

It’s not difficult to understand that ‘Thakur’ has been used as a metaphor for ‘upper caste’ domination. In his autobiography Joothan, Valmiki, who belonged to western Uttar Pradesh’s Muzzafarnagar, talks about influential Tyagis, not Thakurs.

The Rajya Sabha, a domain of political rhetoric and legislative rigour, may not be the most suitable place for appreciating such intricate literary artistry. It is an arena where the language of politics often drowns out the softer tones of poetry, leaving the essence of Valmiki’s creation vulnerable to dilution and misinterpretation.

Jha shouldn’t have recited this poem in the house, and the chair should consider deleting this instance from official records.

Also read: Modi’s Women’s Reservation Bill has an OBC-sized oversight. Undermines inclusivity, fairness

A complex text read without context

Jha started his speech by clarifying that he wasn’t referring to any specific group or caste. He used the poem to show how some people tend to dominate others. “I meant to say that so long as we do not get over this tendency, we cannot think about the welfare of subalterns,” he told The Indian Express.

This is exactly the problem with reading complex texts as rhetorical speeches because the details and context are often lost in translation.

Stripped of its original context and setting, the poem might inadvertently fuel the notion that the Thakur or Kshatriya caste shoulders sole responsibility for rural dominance and associated wrongs. Caste dynamics are complex, woven intricately into the fabric of Indian society, resembling a tapestry of graded inequality. In the context of dominance, caste must be seen in the plural.

Reducing this reality to a blame game oversimplifies a deeply rooted social phenomenon.

Also read: Udhayanidhi’s ‘eradicate Sanatana’ not a call to genocide. It’s internal critique of Hinduism

Thakurs don’t dominate everywhere

While the Thakurs may hold sway in specific regions, this narrative does not hold true for the whole of India. For instance, when in West Bengal, Brahmins, Vaidyas and Kayasthas are the dominant castes.

Even in states like Punjab and Haryana, Thakurs do not enjoy a predominant position. If taken literally, Thakur ka Kuan is not telling the truth about land relations in Punjab and Haryana.

This illuminates the diverse and intricate nature of India’s caste system, demonstrating that it cannot be neatly confined or attributed solely to one specific group. In some areas, Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and intermediate castes are more dominant – a particular reality in rural areas. To understand this phenomenon in rural (not urban) settings, one may like to read ‘the concept of dominant castes’ proposed by sociologist MN Srinivas in his essay on the social system of a Mysuru village.

Society is changing, and so are the socio-economic equations. The Thakur community, which was once very powerful in parts of northern India, has seen big changes in their fortunes. This happened because of important government decisions like getting rid of the zamindari system, abolition of privy purses, rules about maximum land holdings, and the rise of a market-driven economy. Holding on to old ideas in this fast-evolving environment is wrong and stops us from moving ahead.

If we don’t recognise these changes, we might end up being stuck in the past. The contribution of agriculture to the country’s GDP has reduced significantly, about 18.2 per cent as of 2022-23. It implies that the traditional agricultural communities are not prospering. Rather, their sway is on the wane. That’s also true for traditional land-owning communities. The transformation of the Indian economy from agrarian to service and manufacturing-oriented has reduced the clout of land-owning castes like Thakurs.

Even the primary site of oppression and domination has changed from khet, kuan, and talab to the corporate world, universities, media, and judiciary. In most cases, there will be no Thakurs dominating these arenas.

Had he perceived this, Jha would probably cite the example of Brahmins. There are numerous Hindi stories and poems he could have recited to make his point. Why choose Thakurs? His choice could have something to do with popular culture. After all, Hindi movies have stereotyped Thakurs as oppressors.

A Dalit reciting Thakur ka Kuan and a Brahmin Jha reciting the same thing have entirely different connotations.

It also glosses over the fact that the Thakurs heralded two of the biggest social justice initiatives of post-independence India. VP Singh, a Thakur from the erstwhile Manda Estate in UP, implemented the Mandal Commission Report and thus opened the doors of bureaucracy for backward classes. Another Thakur from Madhya Pradesh’s Churhat, Arjun Singh, during his tenure as Union HRD Minister, secured 27 per cent reservation for OBCs in higher education. These decisions changed Indian society forever.

So, it would be wrong to brand all Thakurs as casteists.

Thakurs have voted substantially for the RJD in Bihar. Purposefully or by ignorance, Jha has antagonised a crucial voter base, particularly one that has aligned itself with the RJD in significant numbers. Bad politics, to say the least.

Striking a balance between literary pursuit and political pragmatism isn’t easy; it requires careful navigation.

Jha’s invocation of Thakur ka Kuan was not to single out a particular caste. His recital was meant to shine the spotlight on our pervasive inclination toward dominance and to transcend it. Unfortunately, the meaning was completely lost.

Dilip Mandal is the former managing editor of India Today Hindi Magazine, and has authored books on media and sociology. He tweets @Profdilipmandal. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)