The team currently in South Africa is unlike any Indian team of the past. No more than two of those who travelled there in 1992 would make the cut today.

As we prepare for Indian cricket’s great overseas test in South Africa, I am sneaking in to make some outrageous arguments about cricket—I might as well do so on the day the scout-backed hijack of Indian cricket by a cabal of retired judges and bureaucrats celebrates its first anniversary, without any of the so-called reforms implemented as yet.

If Indian cricket has, unmindful of this, continued to rise, it is because of its class shift over the 25 years since our first visit to South Africa in 1992. The old generations of Oxbridge/Hindu-Stephen’s “good boys” and “graceful losers” have now fully yielded ground to small-town or urban HMT (Hindi Medium Type) “bad boys”.

Next, standards have improved so phenomenally in the past 25 years that not more than three of our pre-1992 cricket stars (Gavaskar, Viswanath and Kapil Dev) would feature in an all-time great Indian squad of, say, even 18 today. In fact, of the squad that went to South Africa in 1992, only two would make it—Kapil and Tendulkar. Please note that of these, the oldest, Viswanath, made his debut in 1969. So, nobody who played in 115 Tests between 1932 and 1969 would make the cut.

This much for the school of the great nostalgia-wallahs who pine for the gentle spin of Bedi and Prasanna and languid cover-drives of several others. All of them, except Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi, won’t make it today because they can’t pass the fielding and athleticism test. Pataudi won’t make it with his batting average.

I shall, in fact, go ahead and make a more contentious point: while our old spin-quartet (Bishan Singh Bedi-Erapalli Prasanna-B.S. Chandrasekhar-S. Venkataraghavan) was brilliant, it isn’t our all-time great. Four other more recent spinners—Anil Kumble, Harbhajan Singh, Ravichandran Ashwin and, hold your breath, “Sir” Ravindra Jadeja—have left them way behind.

I have two accomplices. The first is India’s finest cricket statistician Mohandas Menon. The second is a recent book, Numbers Do(n’t) Lie (Harper Collins) by a brilliant data-crunching team’s Impact Index, and explained by former Test opener and now commentator, Aakash Chopra. Menon is responsible for my statistical evidence, and Numbers Do(n’t) Lie for the logic that it takes more than just anecdotes and nostalgia to make a player great. Otherwise, I wouldn’t go this far. It is one thing to argue with political establishments; sacrilege to challenge cricketing iconographies.

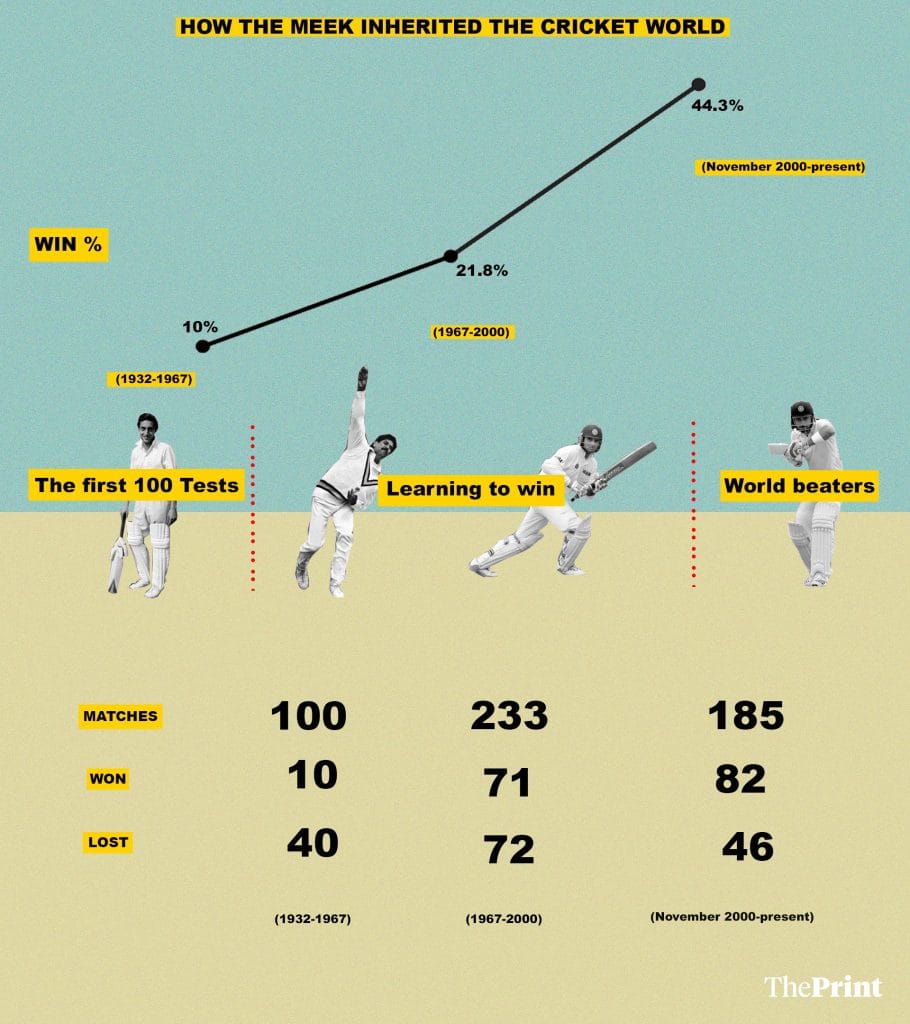

India played its first 100 Test matches between 1932 and 1967, won just 10, and lost 40. In this hoary period, we were no better than Bangladesh of today, which has 10 wins in 104 Tests played since 2000. Never mind the romance of Vinoo Mankad, Lala Amarnath, Polly Umrigar, Pankaj Roy, C.K. Nayadu, Subhash Gupte, Nari Contractor, Bapu Nadkarni, Nawab of Pataudi, Chandu Borde, Salim Durrani, and so on.

In the following 25 years (1967-91), that winning percentage doubled, with 34 wins out of 174. It would have been worse if South Africa weren’t barred by apartheid then.

The win percentage doubled again in the next 25 year (1992-2017) to 39.9 per cent (99 wins out of 248).

Another delicious twist: In November 2000, Sourav Ganguly, the original “bad boy” of our cricket, took over as captain. In the subsequent 185 Tests, our winning record improved further (82) and losses fell (46). In fact, as Menon reminds us, since then, India’s win record of 44.3 per cent is a creditable third, behind only Australia (60.1) and South Africa (49.1), and ahead of England, Sri Lanka and Pakistan.

You don’t need a statistician to tell you that what also increased with the Ganguly era was Indian cricket’s share of nasty controversies. He loved fighting fire with fire, out-sledged the Aussies, waved his shirt and revealed a bare chest on the balcony of Lord’s—all things his predecessors would have disapproved of. We must, however, credit Sunil Gavaskar with making a beginning by dismissing county cricket as something no more than a few beer-drinking old men and dogs watched in afternoons, and declining an MCC invite after he had been first denied entry.

Ganguly’s rise coincided with the social transformation in Indian cricket as rugged, small-town, non-English medium and non-collegiate players (including Sachin Tendulkar) made it to the team. There was a real “hormone burst”, if we were to use a description lately made trendy by Maneka Gandhi. It wasn’t confined to cricket. In the same period, Indian hockey changed, doubling its dismal winning record against Pakistan. Leander Paes, who may have a fraction of the talent of Ramesh Krishnan or Vijay Amritraj, tasted more success in Davis Cup and on the doubles ATP tour.

This was a win-at-all-costs new generation of Indians. Keeping pace was the arrival of a succession of hardball businessmen or politicians as leaders of the BCCI. The era of anglophile princes and tycoons was over. Jagmohan Dalmiya and Ganguly, I.S. Bindra, Lalit Modi, and N. Srinivasan were a far cry from Vijay Merchant, Raj Singh Dungarpur, Madhav Rao Scindia, R.P. Mehra, Fatehsingh Rao Gaekwad, and the finest gentleman of all, the Maharajkumar of Vizianagaram or Vizzy. For that generation, hosting a visiting English team in their palaces was a highlight of their cricketing dalliance. Now, India was stepping into the era of flaunting bare knuckles—and chests.

That’s the change the Indian cricket conservative as well as the old establishment (England-Australia) are not able to digest, for different reasons. Current Indian spinners may or may not be in the Bedi/Prasanna class. But one thing you’d never see them do is applaud a batsman for hitting them for four. It will likely be a curse word.

Before the era of Ganguly, Kapil Dev was our first truly rustic, aggressive cricketer. He swallowed physical pain and public humiliation as Kepler Wessels knocked him with his bat, leaving an awful bruise on his shin for “Mankading” Peter Kirsten at Port Elizabeth in December 1992. Will somebody do that to Virat Kohli, Ishant Sharma or Ashwin? Jadeja? How will Kohli’s India respond to a John Lever-Vaseline ball-tampering scandal? A Sabina Park massacre like April 1976, which Gavaskar called, in his book Sunny Days, “Barbarism in Kingston”.

Imran Khan has a story on how he transformed his barely literate Punjabi-speaking new team into world-beaters late-1970s on. He made them shed their fear and deference of the foreigner. Wear salwar-kameez at official events if you couldn’t handle a suit and tie, never address a rival as “sir”, never say sorry for anything, and curse when you need to, in Punjabi if you don’t know English. They will understand.

That’s the revolution in Indian cricket since Ganguly. Kapil Dev, big-hearted enough to speak at Aakash Chopra’s book release though he didn’t make the cut among the list of India’s impact players, made a great point. In the old, “Bombay school” of batting, he said, batsmen hit the ball but didn’t look the fast-bowler in the eye for fear of angering him. Now Kohli hits them, and says, “go, fetch”.

This is what our genteel, well-intended new board has been trying to reverse with its romantic notions of what they erroneously believe is still the gentleman’s game, sucking up to the ICC, giving up India’s clout, leaning on the Indian team to calm down after Steve Smith’s disgraceful DRS “brain-fade” in Bengaluru.

Postscript: Who are our greatest spinners? Ashwin, at a wicket per 52.8 balls has the world’s highest strike rate for any spinner since World War II, or 1945. He’s ahead of Murali (55), and Warne (57). For India, Jadeja and Kumble come next with 61.2 and 66, respectively. Of the old quartet, Chandrasekhar stands with Kumble at 66; Prasanna (76), Bedi (80) and Venkat (95) trail way behind. Bhajji is above them at 69.

That’s why none of them features in the Impact Index/Aakash Chopra list of impact players and, frankly, however sad it may seem, none of the four will make it to the current Indian squad. Purely on spin-bowling talent, even if we discount the issue of throwing under-arm or “bowling” back to the wicket-keeper, something you haven’t seen from Indian fielders for three decades now.

India was the first country to tour South Africa in 1992 after the end of the apartheid era ban on sporting contacts. Shekhar Gupta covered the historic tour for India Today magazine from South Africa.

All stats updated till 1 January 2018.

As I read this marvellous article by Shekhar Gupta, I have watched a terrific batting performance by Hardik Pandya on Day 2 of the 1st Test between SA & India. Bravo.

We can’t ignore Eknath solker,Mohinder Amarnath and karsan ghaweri.kapil dev’s approach was offensive not defencive. And one more extraordinary Spiner Laxman shiva Rama Krishnan.