With Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s BJP winning an even bigger mandate in 2019, many expected the Budget to take a string of bold decisions to jump-start India’s economy. The Budget presented by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, like almost all budgets presented by the Bharatiya Janata Party since 2014, proposed incremental changes. These conservative budgets are in sharp contrast to the images Modi projects of himself — a populist, a disruptor. Why is a self-described populist pursuing gradual policy changes? Other populists, like United States President Donald Trump, have disrupted patterns of global trade, immigration, and different forms of international engagement.

Politicians such as India’s Narendra Modi, USA’s Donald Trump, Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, and Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu are some of the populists in power in many parts of the world. Populist politicians are charismatic, consider themselves to be the vanguard of popular will, and display a hint of disdain towards the elites and oversight towards the non-elected institutions like the press and the civil society (which they believe serve vested interests), even though populism remains hard to define.

Despite holding power since 2001 (when Modi became the chief minister of Gujarat), the prime minister presents himself as an outsider and anti-elitist, the principal attribute of populist politics that has been a central feature of Modi’s rhetoric. He has not shied away from using his humble beginnings to present himself as an outsider in Lutyens’ Delhi. During the 2019 Lok Sabha election, the prime minister, in an interview with The Indian Express, claimed that his public image was because of his hard work and couldn’t be attributed to the ‘Khan Market gang’ or Lutyens’ Delhi. Anti-elitism appears to resonate with the Indian electorate, especially with the aspirational Indian youth.

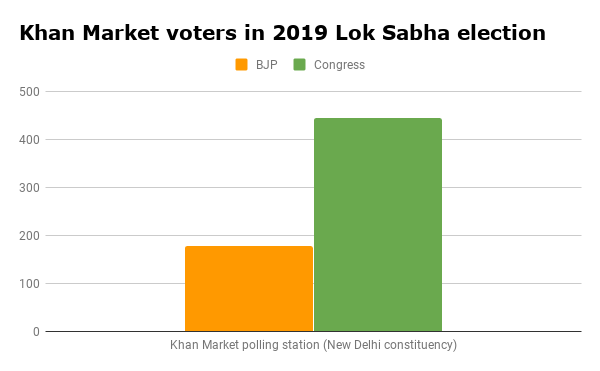

It is important to understand that though this anti-elitism may seem to be empty rhetoric from a political-electoral strategy standpoint, it is often based on some notions of truth. Otherwise, it would be hard to sell it to a larger public for a sustained period of time. There is some evidence that even in 2019, India’s social and economic elite did not vote for the BJP. In the National Election Studies (NES) survey conducted by Lokniti-CSDS, those who regularly read English newspapers (a proxy for the Indian elite) were less likely to vote for the BJP than those who read newspapers in other languages (or even watched English news channels). Despite losing the New Delhi constituency in the 2019 election by a considerable margin (more than 2.5 lakh votes), the Congress party got more votes than the BJP in some of the affluent Lutyens’ Delhi neighbourhoods such as Bhagwan Dass Road, Mansingh Road, Mandir Marg, Lodhi Colony, and Khan Market. In the Khan Market polling station, Congress’s Ajay Maken received 446 votes while BJP’s Meenakshi Lekhi got only 178 votes out of the total 674 votes polled.

It is important to understand that though this anti-elitism may seem to be empty rhetoric from a political-electoral strategy standpoint, it is often based on some notions of truth. Otherwise, it would be hard to sell it to a larger public for a sustained period of time. There is some evidence that even in 2019, India’s social and economic elite did not vote for the BJP. In the National Election Studies (NES) survey conducted by Lokniti-CSDS, those who regularly read English newspapers (a proxy for the Indian elite) were less likely to vote for the BJP than those who read newspapers in other languages (or even watched English news channels). Despite losing the New Delhi constituency in the 2019 election by a considerable margin (more than 2.5 lakh votes), the Congress party got more votes than the BJP in some of the affluent Lutyens’ Delhi neighbourhoods such as Bhagwan Dass Road, Mansingh Road, Mandir Marg, Lodhi Colony, and Khan Market. In the Khan Market polling station, Congress’s Ajay Maken received 446 votes while BJP’s Meenakshi Lekhi got only 178 votes out of the total 674 votes polled.

This is not to suggest that the BJP did not do well in affluent neighbourhoods in the 2019 election. As polling booths often comprise mixed neighbourhoods, it is difficult to make any such observation with statistical precision. In fact, the BJP outperformed its nearest rivals in many booths that could be described as ‘affluent’ across the country.

Also read: Time Modi & Amit Shah stop abusing Lutyens’ Delhi. They are the new power elite in Capital

Populists present themselves as anti-elitist, but they differ in the policies they adopt and how they adopt them. Populists can be Right-leaning (Narendra Modi) or oriented to the Left (Indira Gandhi). They may have humble beginnings (Mayawati) or have an aura of stardom before entering politics (Jayalalithaa or even Donald Trump). Some populists pursue disruptive policies, and their disruptiveness is influenced by whether they are a rank outsider to the political system (Arvind Kejriwal) or have risen through the rank and file of a political party or parties (Narendra Modi).

Outsider populists like Arvind Kejriwal or even Donald Trump are less likely to pursue conventional policies or strategies. It took a couple of years for the Delhi chief minister to complete his transition from being an activist to a full-time politician holding top public office. During this period, Arvind Kejriwal was known for his frequent dharnas (strikes) and constant run-ins with the Lieutenant Governor of Delhi. On the policy front, Kejriwal deserted a dedicated focus — reducing the city’s pollution — after the failure of his odd-even policy. There is a similar, well-known sense of unpredictability in Donald Trump’s decision-making, too, especially when it comes to foreign policy.

Narendra Modi, while presenting himself as an outsider to Delhi, has risen through the ranks of a mainstream political party. Modi has held various organisational positions within the BJP, and was Gujarat’s chief minister for more than a decade before becoming the prime minister. Leaders like Modi have a dual objective — of ensuring their own rule while also simultaneously extending the electoral and ideological domination of their respective parties.

Populist regimes led by leaders embedded in mainstream political parties prefer gradualism over disruptive big bang reforms. In Modi’s first tenure, critical reforms like the GST were introduced in consultation with the state governments. On many fronts like disinvestment and enabling foreign direct investment, the Modi government moved cautiously, often drawing the ire of its libertarian supporters for being too slow. The government was even forced to withdraw some prominent reforms like the land acquisition bill due to public pressure.

Also read: The holier-than-cow Indian liberal elite is actually Modi’s best friend and ally

Moreover, except demonetisation, which was perhaps the only ‘shock and awe’ policy decision, there is a fair bit of predictability in the policy-making under Modi’s rule. Many policy decisions taken by Modi conform to the ideological position of the BJP, with a few instances of deviation. While ‘shock and awe’ would remain an arsenal in every populist leader’s portfolio, those who come from mainstream parties will rarely use it. Moving forward, Modi will continue to present himself as an outsider even though the policies he pursues are more incremental than radical.

Pradeep Chhibber and Pranav Gupta are with the University of California at Berkeley, US. Rahul Verma is a Fellow at the Centre for Policy Research. Views are personal.

This article has been updated to include additional information.

Indeed a non sensical article. Modi as a politician knows the pulse of the people. His agenda is clear like Congress ( corruption culture) Mukt Bharat, 5 trillion dollar economy, etc. But he has definite ideas on how to proceed. At times it is incremental and at times it is a shock. He is here to be at the helm for next 10 years at least and by 2029, India would have changed substantially and for better.

What an incredibly stupid article? Also this has no relevance to the Indian audience!! But then what can you expect from “academics” who try to put a theory on everything. Guys, go out and get on the ground to see what really is happening in Bharat instead of sitting in California and writing complete crap