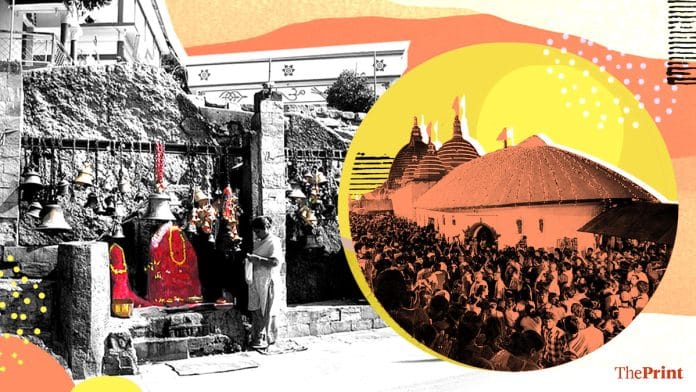

The Kamakhya Temple in Guwahati, where one of South Asia’s largest religious festivals is happening this week, is an extraordinary centre of the subcontinent’s history. Underneath the temple is a natural spring in a cave, around which kingdoms rose and fell and diverse ethnicities and religions were assimilated over the centuries. The history of the Kamakhya Temple, particularly, encapsulates the history of Northeast India — and challenges the way we imagine the spread of Hinduism.

Descending from a demon

Claiming association with divinity has always had beneficial political implications, but one of the earliest known inscriptions from Assam does the opposite—claiming that a royal donor was descended from a demon. Dating to the 7th century, it begins by eulogising a demon, Naraka, conceived when the boar-god Varaha, a form of Vishnu, retrieved the Earth goddess from the bottom of the ocean. The inscription praises him as “powerful enough even to torment the ambrosia-drinking gods, and all-powerful on earth, being the king-of-kings”. According to this inscription, it is from Naraka that the donor Bhaskaravarman, King of Kamarupa—the ancient kingdom of Assam—was descended.

Why make this claim? The answer lies in Assam’s historic ethnolinguistic diversity, a feature that it shares with other states in India’s Northeast, including Manipur and Tripura. In The Cross-Cultural Kingship in Early Medieval Kāmarūpa: Blood, Desire and Magic, historian Paolo Eugenio Rosati argues that speakers of Indo-Aryan languages moved into the Brahmaputra river valley of Assam between the 2nd century BCE and 1st century CE, bringing with them the worship of emerging gods such as Vishnu and Shiva. But the valley was already populated with many peoples, referred to rather dismissively in Gangetic texts as mleccha—barbarian. These communities worshipped female nature deities with aniconic symbols and ritually offered meat and liquor.

In contrast, the new immigrants worshipped primarily male deities with iconic symbols, and their Brahmanical worldview regarded meat and liquor as impure. Intermarriage and cultural negotiations occurred as the earliest states began to form by the 4th century CE. It is around this time that the Bhaumas—literally meaning “of the earth”, the dynasty of King Bhaskaravarman—took root in the region.

To the Bhaumas, a local clan outside the pale of the Sanskritic universe, a claim of demon descent allowed considerable flexibility. On the one hand, Naraka, as the son of the god Vishnu, was linked to emerging pan-Indian traditions that saw Vishnu as the premier royal god. On the other, Naraka was believed to have been conceived when the Earth goddess was menstruating, a taboo act that influenced his nature and made him “demonic”.

As Naraka’s descendants, the Bhaumas thus had legitimate reasons to participate in and negotiate with the traditions of their hill-people subjects, even if the Brahminical priesthood saw these practices as impure. Counterintuitively, then, while other medieval royal lines gained legitimacy from divine descent, in Kamarupa, this came from demonic descent. This is just one of the many creative ways in which the peoples of this region engaged with the Sanskritic mainstream of medieval India.

Also read: Mahabharata war to Dasaratha sacrifices—Tripura’s Manikya dynasty used religion as a force

Appropriating the primordial goddess

The rise of the goddess Kamakhya follows a similar dynamic — a creative engagement with the Sanskritic mainstream, remaining firmly rooted in local tradition. In fact, Kamakhya’s popularity was such that worshippers actually began to nudge back and shape the Sanskritic mainstream.

On a hill near modern-day Guwahati, before her emergence in the 8th-9th centuries CE, Kamakhya had been worshipped for hundreds of years, with rituals that included animal sacrifices, possession, and frenzied dance. As religious studies professor Hugh Urban writes in The Womb of Tantra, Kamakhya was originally one among many goddesses worshipped by local hill-peoples. The Khasis, for example, worshipped a goddess called Ka Meikha, Old Cousin/Mother; the Jaintias offered blood sacrifices to a mother goddess; the Chutiya kings, probably of Bodo origin, worshipped the goddess Kechai Khaki who was believed to eat human flesh.

In Yoni, Yoginīs and Mahāvidyās, historian Jae-Eun Shin traces how Kamakhya rose to become perhaps the region’s single-most popular goddess. Around the same time the Bhaumas were consolidating power, a new religious force emerged in South Asia: the worship of yoginis, who were fierce, flesh-eating goddesses. They were propitiated using esoteric tantric rituals that were also being used by Shaivites and Buddhists. Another significant development was the composition of a text called the Devi Mahatmya, which argued that all goddesses were manifestations of the primordial Adi Shakti.

By the 9th century, yogini worship had entered the mainstream in Kamarupa, where non-Brahminical rites already had a significant presence. In fact, as Urban argues, rather than a uniform process of locals being “Sanskritised” or “Hinduised”, the emergence of tantra actually involved a complex assimilation from both directions—a dynamic we’ve seen elsewhere in Thinking Medieval. The Mlechchha dynasty of Kamarupa, which overthrew the Bhaumas, constructed a massive stone temple at the Kamakhya spring in the 9th-10th centuries, which continued to receive grants from their successors, the Palas, in the 11th-12th centuries. A number of small shrines were also built for yoginis, both on this hill and at other sites in Kamarupa. But most importantly, a brilliant text called the Kalika Purana was composed during this time, making a potent new argument about the primacy of the goddess Kamakhya, reinventing her as an eternal deity of the region.

Appropriating the earlier myth of royal descent from Naraka, the Kalika Purana claimed that Naraka had conquered Kamarupa with the assistance of his father, Vishnu, after which he was commanded to worship Kamakhya. This helped legitimise royal worship there. Next, taking a cue from the Devi Mahatmya, it claimed that this ancient hill-goddess was actually a manifestation of a pan-South Asian goddess. It invented an origin story of the natural spring, claiming that it was actually the yoni or vulva of Sati, the wife of Shiva, which had fallen from her corpse when Shiva carried it around in grief after her self-immolation. The yogini deities, once popular in their own right, were presented in the Purana as subordinate protectors of Kamakhya, further elevating her status.

Next, the Purana provided rituals for Kamakhya’s worship: the sacrifice of wild animals and even humans. These are contrary to medieval Vedic practice, but very much in line with religious practices among the surrounding hill-peoples. Finally, the Purana provided for the ritual consumption of reddish water from the spring, described as the goddess’ menstrual blood and praised for granting magical powers to Kamarupa’s kings. The cumulative effect of all this: Kamakhya exploded in popularity from a local goddess to a royal one, and from a royal goddess to a mainstream Hindu deity. All while very much maintaining her ancient tribal roots and rituals.

As you read this, the red waters of the adjacent Brahmaputra are being worshipped by millions of devotees from the Hindu mainstream as the sacred menstrual blood of the goddess. There is no equivalent of such a phenomenon anywhere else in India. This is the ultimate sign of the success of the Kalika Purana, a sign of how powerful religious literature in South Asia can be.

As with Manipur and Tripura, some politicians have been eager to interpret all these developments as “Hinduisation”, seeing this as proof of the Northeast having been “Hindu” or “Indian” from an early period. However, the goddess Kamakhya seems to also tell the opposite story: a local tradition adopting elements of Sanskritic tantric ideas to elevate itself, presenting itself as magically efficacious, capturing royal patronage. There is much more to say about Kamakhya’s later history, particularly when Assam was invaded by Delhi and the Ahoms and on the goddess’ complex relationship with the Koch Behar royals. We will return to this in next week’s Thinking Medieval.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)