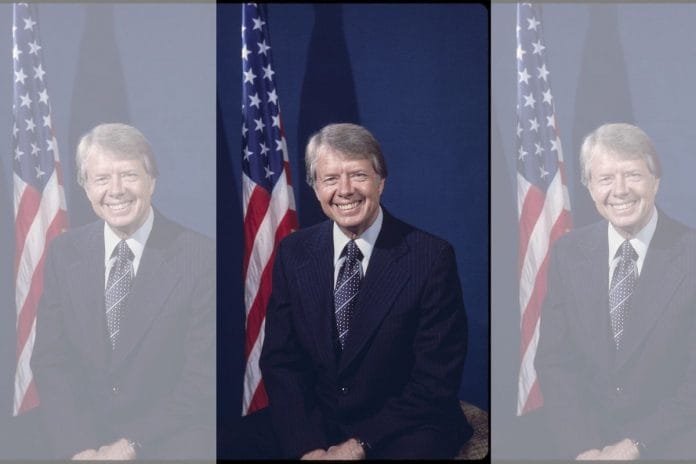

Former US President Jimmy Carter, who passed away on 29 December, will be remembered as a well-meaning, if somewhat naïve, leader who represented a period of transition for the US—from a hamstrung, stumbling power that couldn’t do anything right to one with a renewed self-confidence and verve. Though he could not entirely reset America’s relations with India, he did start the two countries back on the path toward some normality after the rocky years under Richard Nixon.

As President, Carter repudiated many aspects of US foreign policy and wanted to focus more on human rights and arms control. He also sought genuinely better ties with India. But US relations with India during his presidency—from 1977 to 1981—were as mixed as always, starting with a familiar mutual hope and ending in an equally familiar mutual frustration.

The Carter-India connect

He did have some acquaintance with India through his mother, who had spent time in the country under the US Peace Corps programme a decade earlier. Carter’s desire for a change of direction coincided with Indian hopes, still angry about Nixon’s support to Pakistan during the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. Carter acted on these sentiments, sending his deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher to India, without the usual stopover in Pakistan, in 1977. Carter himself visited India in January 1978, again without stopping over in Pakistan. The visit was pleasant enough but became notable for a ‘hot mic’ moment where Carter was overheard telling his officials that he intended to send a “cold and very blunt” letter to then-Indian Prime Minister Morarji Desai over US-India disagreements on the nuclear issue.

The nuclear disagreement was a key obstacle in improving bilateral ties between India and the US. Carter came to the White House determined to strengthen the global nuclear non-proliferation order. A few months after he reached the White House, the 1977 Lok Sabha elections in India brought Desai to power. Desai was also deeply anti-nuclear, dismissing any need for Indian nuclear tests. This should have made for some common ground with Carter. But India’s nuclear programme itself was in some trouble, with both Canada and the US stopping nuclear cooperation with India after the 1974 Pokhran nuclear test.

The Soviet Union stepped in to supply India with the heavy water needed for its nuclear power plants but insisted on perpetual safeguards on the plutonium produced in these plants. Carter wanted India to desist from developing nuclear weapons, which Desai accepted so that fuel supplies to the US-built Tarapur Atomic Power Station could resume. Ultimately, Carter couldn’t square the non-proliferation circle, limiting US-India relations.

Also read: What’s behind India’s Ukraine policy, Western hypocrisy & how nations act in self-interest

A tainted legacy

Carter did not fare well elsewhere, either. The US economy was stubbornly unresponsive, leading his successor, 40th President Ronald Reagan, to ask Americans a question that stunned Carter during the 1980 US Presidential elections: “Are you better off today than you were four years ago?”

America’s international standing suffered, too: in the aftermath of the Vietnam War (1955-1975), Soviet proxies appeared to be on the march everywhere, from Southeast Asia to Africa to Central America. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 seemed to be yet another indication of Moscow’s triumphant march. Most of these adventures would sap the USSR’s strength and lead to its collapse in 1991, but the picture in the late 1970s was of a confident Soviet Union and a struggling America.

The most severe blow to Carter was the Islamic revolution in Iran and the taking of American diplomats as hostages in 1979—which appeared to underline American weakness. To make matters worse, Carter’s effort to free the hostages, Operation Eagle Claw, ended in disaster in a desert outside Tehran. His failures overshadowed but did not negate his one significant achievement: The signing of the Camp David Accords in 1978, a first-of-its-kind political agreement between Israel and Egypt that established a framework of peace between the two nations, and redefined politics of the Middle East.

The author is a professor of International Politics at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. He tweets @RRajagopalanJNU. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)