Social media can contribute to polarisation. In a polarised society, citizens with different affiliations may hold different beliefs because they consume different – possibly contradictory – sources of political news.

‘Fake news’ and other forms of misinformation arguably play a key role in this process. False or unsupported claims, if consumed and believed by members of different parties, are likely to increase polarisation, and do so fast.

There is no shortage of fake news circulating online, especially during the campaign for the 2019 Lok Sabha election. In India Misinformed, Pratik Sinha, Sumaiya Shaikh, and Arjun Sidharth brilliantly expose the range of fake claims that have been distributed widely in recent times. As documented in the book (and by fact-checking websites such as Alt News, Boom, and others), inaccurate political information is now propagated on social media on a daily basis. Many of these false claims originate from party affiliates, party groups, or party supporters. Most major political parties now appear to be in the business of spreading dubious information online.

However, is the flurry of fake news Indians experienced during the Lok Sabha election campaign exacerbating polarisation?

This hypothesis is somewhat credible. However, it is important to keep in mind that all political parties may not be equally adept at crafting dubious stories and circulating them among current and potential supporters. Rather, some parties (and their supporters) may be more skilled, which could result in shifts in their direction among all voters – even those who support other parties.

A recent study we conducted suggests that this is exactly what is happening: according to our data, misinformation on social media is not polarising Indians. Its most consistent effect is to make all voters – both supporters and opponents of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) – more likely to endorse claims that support the ruling party.

In the days following the announcement of the election results, we recruited over 1,000 Hindi-speaking Facebook users residing in India and invited them to participate in a study about Indian news and society. (Respondents were offered the chance to win cash and other prizes in exchange for participating.) While our sample was disproportionately male, highly educated, exposed to news, urban, rich, upper-caste and pro-BJP when compared to the overall population of Hindi-speaking states, it nonetheless includes a relative diversity of profiles. More importantly, our sample is highly representative of Hindi-speaking high-frequency social media users – precisely those who are most likely to encounter and distribute fake news online.

Also read: Fake news: Sonia Gandhi in bikini, Rohingyas eating Hindus & Nehru calling Bose a criminal

Belief in true and false claims

As part of this study, we measured these participants’ demographics and a range of general behaviours related to their consumption of news. Most importantly, we measured their self-reported exposure to several accurate and inaccurate claims (via the query: “Have you heard this claim?”) that had been widely circulated online during the last month of the 2019 Lok Sabha campaign. Respondents were asked whether they had heard the claims and whether they believed the claims to be accurate or inaccurate.

Each respondent evaluated 40 different claims: 10 accurate claims and 30 inaccurate. While we had originally collected far more than 40 claims, we deliberately ignored many prominent rumours, so as to keep the study’s length reasonable and to include a diversity of claims – including a number of pro-opposition/anti-BJP claims. The claims appeared to respondents in random order to force them to think about each claim separately. Importantly, every respondent was extensively debriefed at the end of the study and told which claims were accurate and which were false or unsupported by available evidence.

Before considering the results of the survey, two important caveats are in order. First, our sample was not nationally representative. It is possible, for instance, that belief in false claims is more common among less educated and less urban Indians, who are underrepresented in our sample. It is, however, also possible those less connected respondents would be less likely to believe this misinformation; not being exposed to it online, they may remain oblivious to it.

Second, the results of any study like ours may be sensitive to the particular set of rumours we selected. It is worth mentioning that the universe of existing false claims is not random; it was heavily focused around the BJP and the Congress, and especially so around Narendra Modi and Rahul Gandhi. This pattern may reflect the BJP’s success at getting their preferred claims widely circulated (we consider this possibility below after discussing our results).

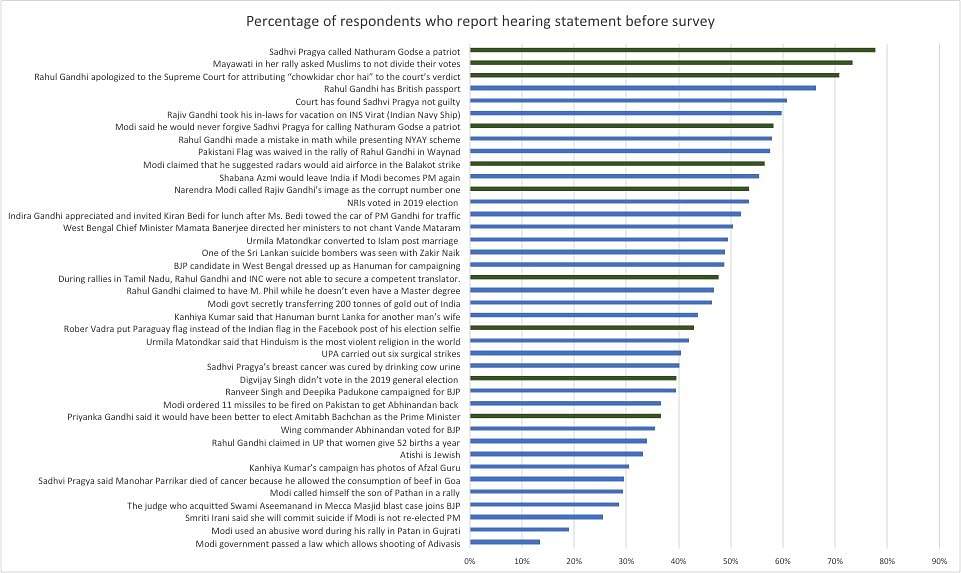

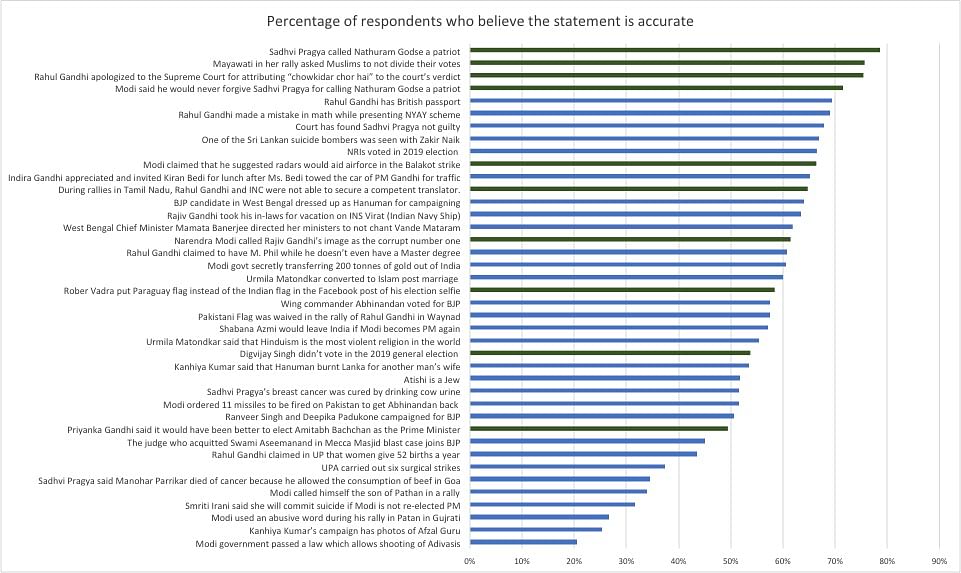

Figure 1 displays the percentage of respondents in our study who reported hearing about each of the claims we studied. We colour-code true claims in green and false or unsupported claims in blue. We repeat this exercise in Figure 2, which displays the average rate of belief in each claim in our study.

Figure 1: Percentage of respondents who report hearing statement before survey

Figure 2: Percentage of respondents who believe the statement is accurate

Taken together, these two graphs neatly illustrate the current misinformation crisis. As seen in the graphs, our respondents had heard of many of the inaccurate statements more than they had heard of the accurate ones (Fig 1). Perhaps more striking, respondents often believed inaccurate statements more than they believed accurate claims (Fig 2). Over 60 per cent of respondents in our sample – both pro- and anti-BJP respondents, actually – said they believed that Rahul Gandhi had a British passport. A similar proportion indicated that they believed that he had made a simple math mistake when explaining the Congress’s NYAY scheme, as many videos circulated online had then alleged. By contrast, a clear majority of respondents appeared to believe the false – but widely circulated – claim that Sadhvi Pragya Singh Thakur had been acquitted in the 2008 Malegaon blast case.

Also read: How Facebook is fighting fake news in the Lok Sabha elections

Who believes what

To understand the possible effect of misinformation on polarisation, we subsequently broke down our data in two ways. We first divided respondents according to their self-reported degree of closeness to the BJP. We separated people who think of themselves as either “close” or “very close” to the ruling party (we call them supporters) from those who think of themselves as either “far” or “very far” from it (we call them opponents). (Our analyses are substantially similar if we distinguish respondents by whether they report having voted or not for the BJP).

Second, we divided the claims that respondents reacted to in three categories: pro-BJP/anti-opposition claims, pro-opposition/anti-BJP claims, or neutral/ambiguous claims. A bit of subjectivity is involved in this classification, but here is how we proceeded: we counted all those claims as ‘pro-BJP’ where a BJP leader said or did something that would make them look good among the majority of the population; by contrast, we counted claims as ‘anti-opposition’ where an opposition party leader said or did something that would make them look bad among the majority of the population. Cases where this assessment was not obvious were classified as ‘neutral/ambiguous’ and excluded from the subsequent analysis. (Our analyses are however not especially sensitive to the addition of these statements as either pro- or anti-BJP, or to their exclusion.)

Breaking down the data in this manner, we can study the extent to which pro- and anti-BJP voters have heard of and believed pro- and anti-BJP claims. In a highly polarised society, we might expect pro-BJP respondents to have heard (and to believe) pro-BJP information at greater rates than anti-BJP respondents. We would, in turn, expect anti-BJP respondents to have heard (and to believe) anti-BJP information at greater rates than pro-BJP respondents. In addition, we would expect each group to hear and believe information favourable to their side more than they hear and believe information favourable to the opposite side.

However, only some of these expectations are supported by our data.

It is interesting to first look at levels of belief in only the true claims in our study (10 of 40 claims are true). As expected, the average rate of belief (across claims) among BJP backers is higher when the true claim is favourable to the BJP (67 per cent) than when it is a claim favourable to the opposition (65 per cent). Slightly larger differences exist among opposition backers, who believe true claims favourable to the opposition more than they believe claims favourable to the BJP (64 per cent compared to 56 per cent). At first glance, these patterns of selective learning suggest that people are more likely to recognise true claims as true when the claims reflect favourably on their party – a tendency that could contribute to polarisation.

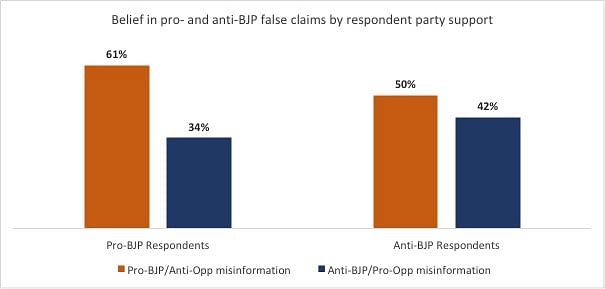

The plot thickens, however, when we investigate these two groups of respondents’ average rate of belief in false claims. As shown in Figure 3, BJP backers are significantly more likely to believe false claims we labelled as pro-BJP/anti-opposition than they are to believe false claims we labelled as pro-opposition/anti-BJP (61 per cent vs 34 per cent). (Results are similar when we restrict the analysis to claims labelled as pro- or anti-BJP.)

Also read: India’s plan to fight fake news before elections is all wrong

Strikingly, we observe this same tendency to endorse pro-BJP false claims among respondents who self-reported being “far” or “very far” from the BJP. As seen in Figure 3, these anti-BJP respondents are more likely to believe pro-BJP misinformation (50 per cent on average across claims) than they are to believe pro-opposition information (42 per cent on average across claims). (This result holds when we restrict the analysis to claims labelled as pro- or anti-BJP.) This willingness of anti-BJP citizens to endorse pro-BJP fake news cannot be explained by the simple partisan rationale above. Rather, both supporters and opponents of the BJP are more likely to endorse pro-BJP false claims compared to anti-BJP false claims.

Figure 3: Belief in pro- and anti-BJP false claims by respondent party support

Misinformation affects public opinion

These results have important implications for how we think about the possible effects of fake news on public opinion and voting in India. In particular, fake news may not have the singular effect of sending partisans further and further into their corners. Rather, we find that pro-BJP fake news is more believable to people across the partisan spectrum. As a result, the BJP likely benefits more than opposition parties from the torrent of fake news circulating around the country.

This imbalance has several likely causes, but it is difficult not to see in these results a sign of the ruling party’s superiority on social media, and more broadly, in the media. Dozens of stories over the course of 2019 election cycle have emphasised the BJP’s superior capabilities on social media and the party’s ever-expanding influence on the media in general. The unique appeal of pro-BJP false claims could be the consequence. When one side has much bigger weapons than the other in the (mis-) information war, it ends up shaping not only what its supporters view as credible – but the likelihood that members of other parties view it as credible as well.

In the short-term, these results highlight the opposition’s difficulty in getting its message across. In the long-term, the consequences could be more worrying. Pro-opposition voters already appear to believe a lot of the pro-BJP false claims made during this election campaign. They have often heard and believed these more than they have heard or believed the claims originating from their preferred parties. This sort of informational dominance is unlikely to hurt the BJP. More likely, these informational advantages could help the ruling party add to its already impressive tally.

Simon Chauchard is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Leiden University; D.J. Flynn is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at IE University; Ritubhan Gautam is a Master’s student in International Affairs at Columbia University.

Keep crying for another 15 years

Nice graphs, excellent phrase of questions and words, twisting of facts, adding fake responses in excell sheet to fill numbers and good English. There you go. A lie told 100 times to make it believe as truth and suddenly becoming saint to show very unbiased and on top of all show some foreign university tag… Walla… you have reached your goal. The article suits the authors how such fake info can be created.

how come can a common believe in your article or any social media article……maybe this whole survey is a fake one ….and nothing like this ever happened ….u are just making this up….or mayb its true ….who knows !!!

Really pratik sinha is himsaelf a fake news peddler