Two recent incidents have drawn attention to the importance of wool, the complexities of its production, and the challenges faced by the pastoral community in India. The first involved Ladakhi pastoralists confronting Chinese soldiers over grazing rights at the border. Second, the recent snowfall and freezing temperatures in the North Western Himalayan region highlighted the necessity of sheep wool for warmth.

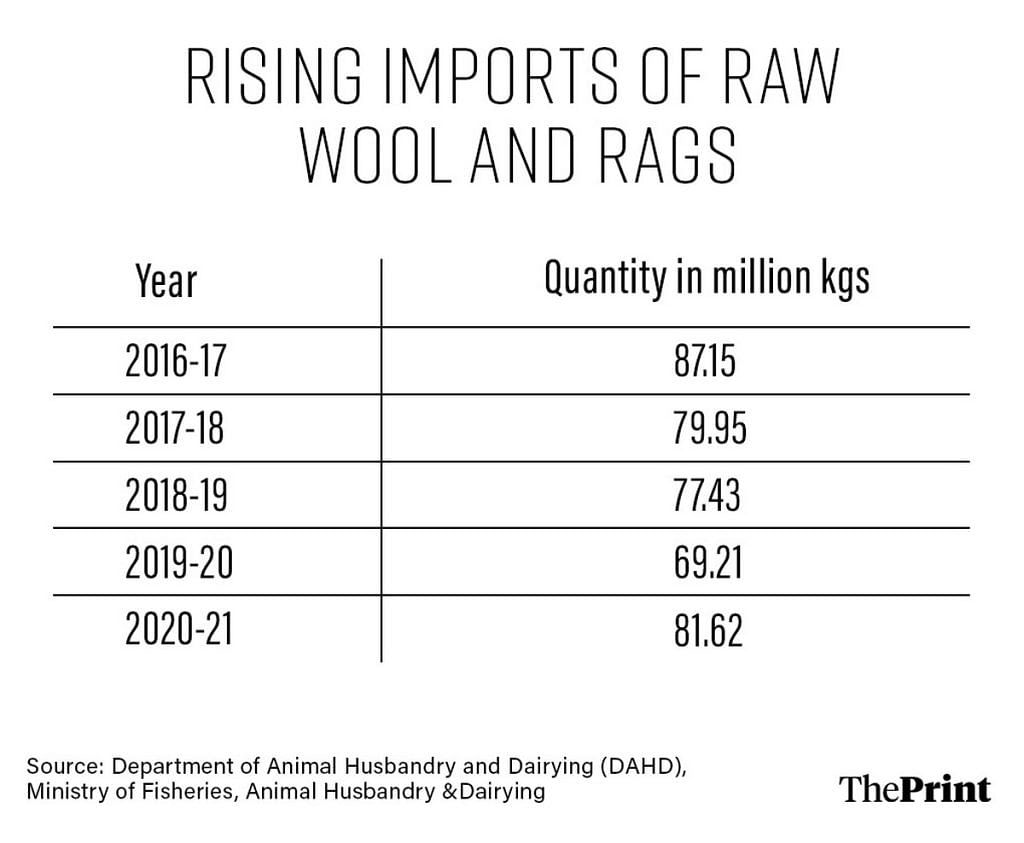

However, it is ironic that despite being home to diverse agro-pastoralist regions and communities, India depends on imports from China, Syria, Australia, New Zealand, and even Egypt to meet over two-thirds of its wool demand. This has essentially turned the country into a dumping ground for wool and wool waste.

Thanks largely to the ruinous policies of successive governments, particularly in the 1990s, coupled with the effects of climate change, the country transformed from producing woollen apparel and other goods to importing raw wool and wool waste.

Also Read: Between China, climate change & development, Ladakhi nomads are losing grip on their land

Import-driven policies are fallacious

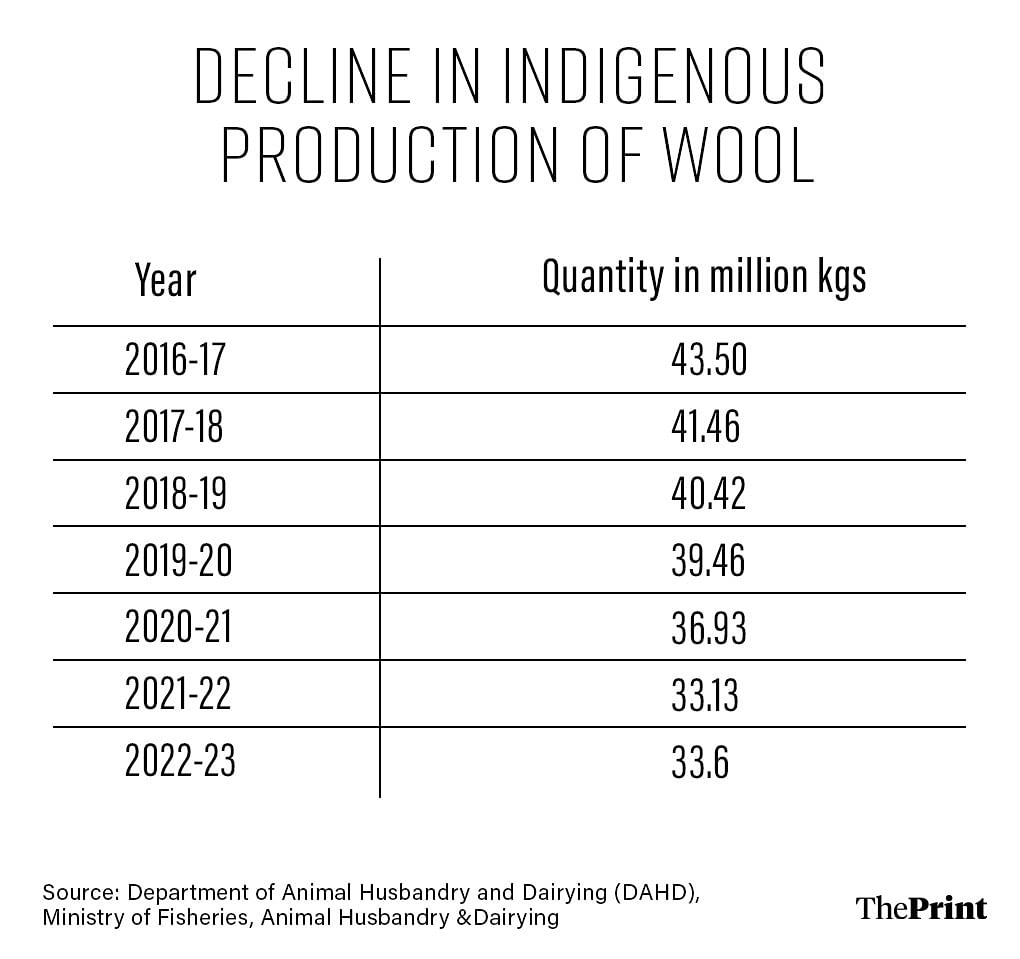

The indigenous production of wool has dropped from 43.5 million kg in 2016-17 to 33.6 million kg in 2022-23.

A key reason for this is the import substitution policies of the current government. Indigenous wool prices have come at par with wool waste prices, as a result of which many breeders shear wool only for the sake of animal health and not for commercial purposes.

For instance, Jammu and Kashmir wool, considered to be the best in the country as far as apparel grade is concerned, was sold at prices ranging from Rs 90 to Rs 110 per kg a few years ago. However, it is now being sold at distress prices of Rs 30 to Rs 35 per kg. These prices do not even cover the basic costs of shearing and transportation. This is the reality for shepherds and wool producers across the country.

The government is promoting cheap imports of raw wool and wool waste from different countries, including China, and in the process dismantling wool production and pastoralists’ livelihoods in the country. The import duty on such wool is negligible, but the concept of minimum support price for Indian wool producers is absent from policy discussions. It is worth noting that wool is not even categorised as an agricultural product, unlike other animal products such as milk. This oversight is particularly troubling considering the historical and cultural significance of wool production and pastoralism in India.

Impact of climate change, land use patterns

One of the major reasons for the decline in domestic wool production is the combined impact of climate change and massive changes in land use on the livelihoods of pastoralists. These factors have led to a significant loss of grazing land and restricted the seasonal movement of pastoralists, affecting their ability to sustain their flocks.

The impact of climate change includes unseasonal snowfall. In 2023, snowfall on 8-9 July severely depleted grazing land in Himachal’s Lahaul and Spiti, leading to the near starvation of sheep flocks. Apart from this, extreme weather events like prolonged dry spells lead to biodiversity loss and a decrease in grazing material.

Similarly, changes in land use patterns in the plains have significantly decreased available settling spaces for the pastoralists, thus impinging on their movements. The pastoralists have migrated seasonally since ancient times. During summers, they climb up the mountains for green pastures there and then descend to the plains in the winters. During these migrations, they traditionally settled in open spaces around suburbs and villages to rest their flock. But with grasslands and pastures being converted to real estate or acquired for development projects, these spaces are diminishing at a very fast pace.

Why wool is important

A natural fibre known for its effectiveness in regulating body temperature, wool also boasts efficient thermal insulation and fire-retardant properties. Wool is used in three different categories: apparel, carpets, and industrial applications like geotextiles. Only 5 per cent of wool is utilised in the apparel industry, with the rest used for carpets and industrial uses.

While some may attribute the high imports of wool to a scarcity of high-quality carpet and apparel-grade wool domestically, this argument doesn’t always hold.

Defence procurement, for instance, could be a major area of wool absorption and consumption in India.

Presently, this market is dominated by Australian wool for uniforms and blankets owing to its finer grades, prized for being lightweight and with a smooth finish, typically measuring between 18-22 microns in thickness. Indian apparel-grade wool tends to be thicker at above 24 microns.

However, finer thickness doesn’t necessarily equate to superior quality. The US and UK armies, for instance, use coarser grade wool for their blankets and apparel, ranging from 24-26 microns, due to its superior warmth and felting (durability and resistance to wear). In Himachal Pradesh, the Gaddi community uses a highly felted gardu blanket. These large traditional blankets, made of coarse wool, excel in withstanding extreme cold and repelling water during persistent rains. This material could easily be used by armed forces in the border regions. Heavier is not bad and has stood the test of time! Our defence forces should consider this rather than opting for fancier, more fashionable, and lighter products.

Also Read: Will saffron bring new riches to Arunachal? Women in Menchukha betting big on purple flowers

Where there is a wool…

To revive domestic wool production, there needs to be a convergence of policies and interventions from the Union and state governments as well as local communities.

The first step is to recognise the importance of pastoralism. There must be a policy shift from plantations to developing grasslands for fodder.

The current practice of indiscriminately planting exotic tree species, such as pine in Uttarakhand, is detrimental to local biodiversity and a major reason for forest fires. Instead, fodder plants must be integrated into plantation drives, as a joint effort by forest, horticulture, and agriculture departments.

Panchayati Raj institutions should also be part of this. Schemes like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) can be leveraged for forest reclamation, including clearing invasive weeds like lantana and ageratum, and the subsequent planting of fodder plants and grasses. These measures will benefit wildlife, pastoralist communities, and even domestic livestock.

Additionally, it is imperative to recognise the rights of forest dwellers and pastoralists through the Forest Rights Act (FRA). It has been almost eight years since the FRA was enacted, but it has still not been effectively implemented.

The lands meant for the resting of pastoralists during their movements should be protected from encroachment and not blindly allocated for development projects like four-lane highways and hydropower plants without creating alternatives.

Take for example the four-lane Mandi-Manali highway. There used to be more than a dozen resting places for pastoralists along the road, but these have been taken over, leaving them with no place to rest during a nearly 120 km stretch. Shepherds are not considered major stakeholders in the environmental impact assessment (EIA) reports of such projects, which is a gap that must be corrected.

Wool production and pastoralism have been inherently linked since the dawn of our civilisation. The current major disruptions, arising either from development processes or policy shifts, can be extremely perilous for not just pastoralist communities but also society at large. Wool production is linked with sheep rearing, and any disruption can have cascading effects even on meat production and the country’s protein supply.

Tikender Singh Panwar was the directly elected deputy mayor of Shimla and is a former president of the Himachal Kisan Sabha. He is a member of the Kerala Urban Commission. He tweets @tikender. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)