Remembering 1962 war with China is good for India’s national security today

India and China, two very ancient civilisations living as close contemporaries, had intimate interaction with each other for centuries. Mao’s Communist China and a liberal and democratic India had friendly relations through the “Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai” jingle till the early 1950s. Then China annexed Tibet and laid claim over large areas in Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh and former North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA). What began as border conflicts spanned into a full-scale war that culminated into a debacle for India in 1962.

The 1962 debacle with China taught us a lesson to be more realistic in politics and diplomacy. The almost non-existent civil-military relationship was established and later institutionalised. Many books, articles and reports have been published on the 1962 war including the much publicised ‘Henderson Brooks-Bhagat report’ and the lesser known History of the Conflict with China, 1962 by the history division of MoD in 1992. Unlike most nations in the West, which witnessed two World Wars, India never witnessed a full-scale war of a larger magnitude before 1962. Again, contrary to the western approach towards wars, India’s political leadership has more or less remained secretive about the cause, strategy, outcome and implications of the wars that were won and lost.

Also read: 56 years later, China can still choke Indian troops the way it did in 1962

Beginning with former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s meeting with Chiang Kai-Shek in 1939, his ideas of a confederation consisting of China, Iran, Afghanistan and India to Chiang’s visit to India in 1942, there was a dream of Asian solidarity.

Then, October 1962 revealed Chinese leadership’s strategy to consolidate its control over Tibet, expand its influence towards south of Himalayas right into the Indian Ocean, and eventually create a string of satellite states around India. Barely a month before October 1962, Pakistan’s Martial Law administrator General Ayub Khan met with President Kennedy convincing him to punish India as a quid pro quo for Islamabad’s decision to not move closer to erstwhile USSR or China.

In the middle of the Cuban crisis and Symington amendment (stipulating a 25 per cent cut in Kennedy administration’s aid to India), New Delhi finalised a deal with USSR for MIG fighter jets against Pakistan acquiring F-104. Nehru’s Asian solidarity dream and misplaced overconfidence went out of the window in a jiffy on 20 October 1962, forcing him to announce in a shaky voice that “we were getting out of touch with reality in the modern world… and we were living in an artificial atmosphere of our own creation…”.

India’s foreign policy and military strategy determined by Her Majesty’s government till 1947 came to be decided by the political establishment later, and hence the responsibility lay at the door of the Prime Minister and his cabinet.

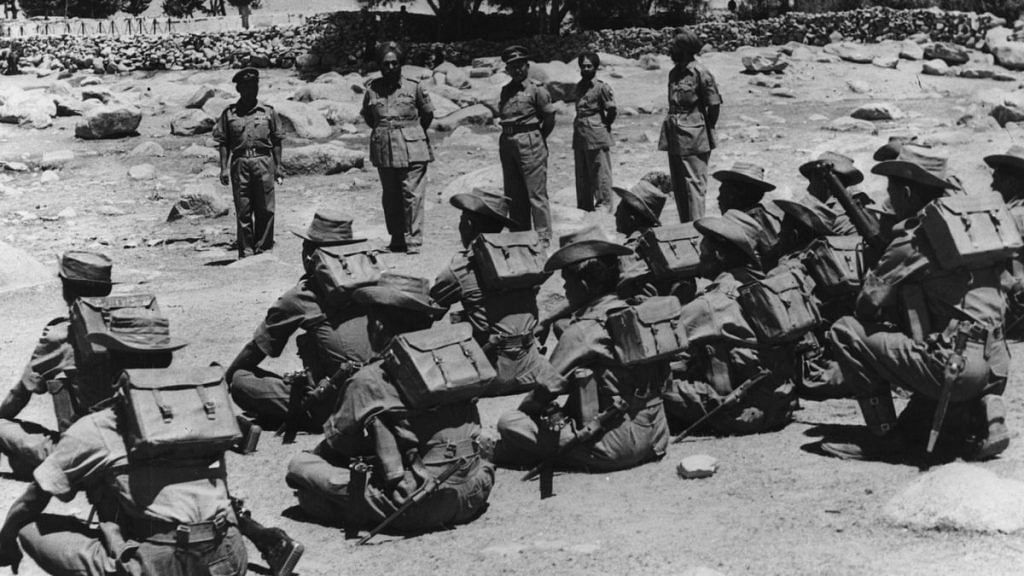

What went wrong in 1962 continues to be a subject of intense debate, research and speculation among the defence and diplomatic communities. Misplaced priorities, shoddy planning and lackadaisical attitude deprived the valiant armed forces of basic military hardware and ammunitions, and rendered them heavily dependent on imported supplies and equipment in the absence of indigenous production and skills. Defence Production Planning Committee was set up in 1957 and Department of Research and Development under Defence Ministry was set up in 1958, but were utterly sloppy and non-functional.

Again, the defence mechanism lacked institutional support and coordinated decision-making process, and suffered from the absence of political-military synchronisation.

Also read: During 1962 war, Nehru was ‘quieter than usual, often in a reverie and sometimes trembling’

Another serious mistake on the part of the military strategists was the decision to not use the Indian Air Force to carry out attacks on the advancing Chinese columns in the Tibet area, where India could have caused heavy casualties and scored a diplomatic point. Needless to say, all these and many other reasons for the debacle are buried under the ‘secret’ and ‘restricted’ clauses somewhere in the bureaucratic labyrinths of the defence ministry.

Lieutenant General T. B. Henderson Brooks, the Corps Commander posted in Jalandhar, Punjab, was appointed to inquire into the 1962 debacle by then-Army Chief General J. N. Chaudhuri who took over after the war. Brigadier Premindra S. Bhagat assisted Brooks in the report. Their report was submitted to the defence ministry in April 1963 and since then remains “top secret”, despite repeated demands for making it public.

If failure is the stepping stone to success, defeat in war can be said to be the best guide to subsequent victory. After the 1962 debacle, India registered an impressive victory frustrating Pakistan’s misadventure in 1965. But as Atal Bihari Vajpayee famously said, (maidaan me jeete, mez par haare) ‘what we gained in the battlefield, we lost on the negotiating table’.

Also read: Not China, 1962 war called India’s bluff

Fifty-six years later, India as a nuclear power is now endowed with resources to gather intelligence, has greater capability to analyse and act, and is militarily stronger and strong-willed to regain lost strategic space in the region, especially in Southeast Asia. Yet, the asymmetrical capabilities between the two ancient civilisations that went to war in 1962 cannot be complacently dismissed. Those who refuse to learn from history are condemned to repeat it.

The author is former editor of ‘Organiser’.