When the Union Budget 2024-25 provided special grants to Andhra Pradesh and Bihar, many other states expressed concerns. Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah alleged that the budget overlooked Karnataka’s interests; the ruling DMK announced state-wide agitations in Tamil Nadu; and Telangana Chief Minister A Revanth Reddy regretted biased treatment.

These reactions highlight long-standing apprehensions among states on fiscal allocations. Yet, there doesn’t seem to be a pathway to address such concerns amicably and sustainably.

All federalism debates revolve around ‘horizontal devolution’, that is, how resources are divided among states. A powerful variant is the claim that the South is disproportionately subsidising the North. But the real problem lies in ‘vertical devolution’, that is, how tax resources are split between the Union government and the states as a whole.

Framing the problem

India tends to have a large vertical fiscal gap, which has been increasing. The reason is that while the Constitution assigns the most buoyant taxation powers to the Union, it allocates more spending responsibilities to the states.

The Union can raise resources through broad-based taxes such as those on personal and corporate income, but the states have large expenditure obligations, particularly in important sectors such as education, health, police, law and order, forests, drinking water, etc. In some sectors, the share of state expenditure is disproportionately high. For instance, states incur 77 per cent of the total government spending on health (2023-24) and 75 per cent on education (2020-21).

The Fifteenth Finance Commission pointed out that although the Union collected 62.7 per cent of the combined revenues of both the Union and the state governments, states alone were responsible for 62.4 per cent of the total expenditure. Moreover, even as the Union’s share in the revenue collections remained more or less the same over time, the states’ share in the expenditure has increased around 10 per cent in the last three decades.

To address this vertical fiscal gap, the broad-based taxes collected by the Union are shared with the states according to the recommendations of the Finance Commissions. However, the increase in the states’ share from 32 per cent to 42 per cent, as proposed by the 14th Finance Commission, has not resulted in a proportionate rise in devolution to the states. This paradoxical situation is due to the increasing share of cesses and surcharges in the Union tax pool, which are not shared with the states. As a result of the lack of effective devolution, the states’ expenditure commitments suffer, affecting the quality of public services and leading to inter-state squabbles.

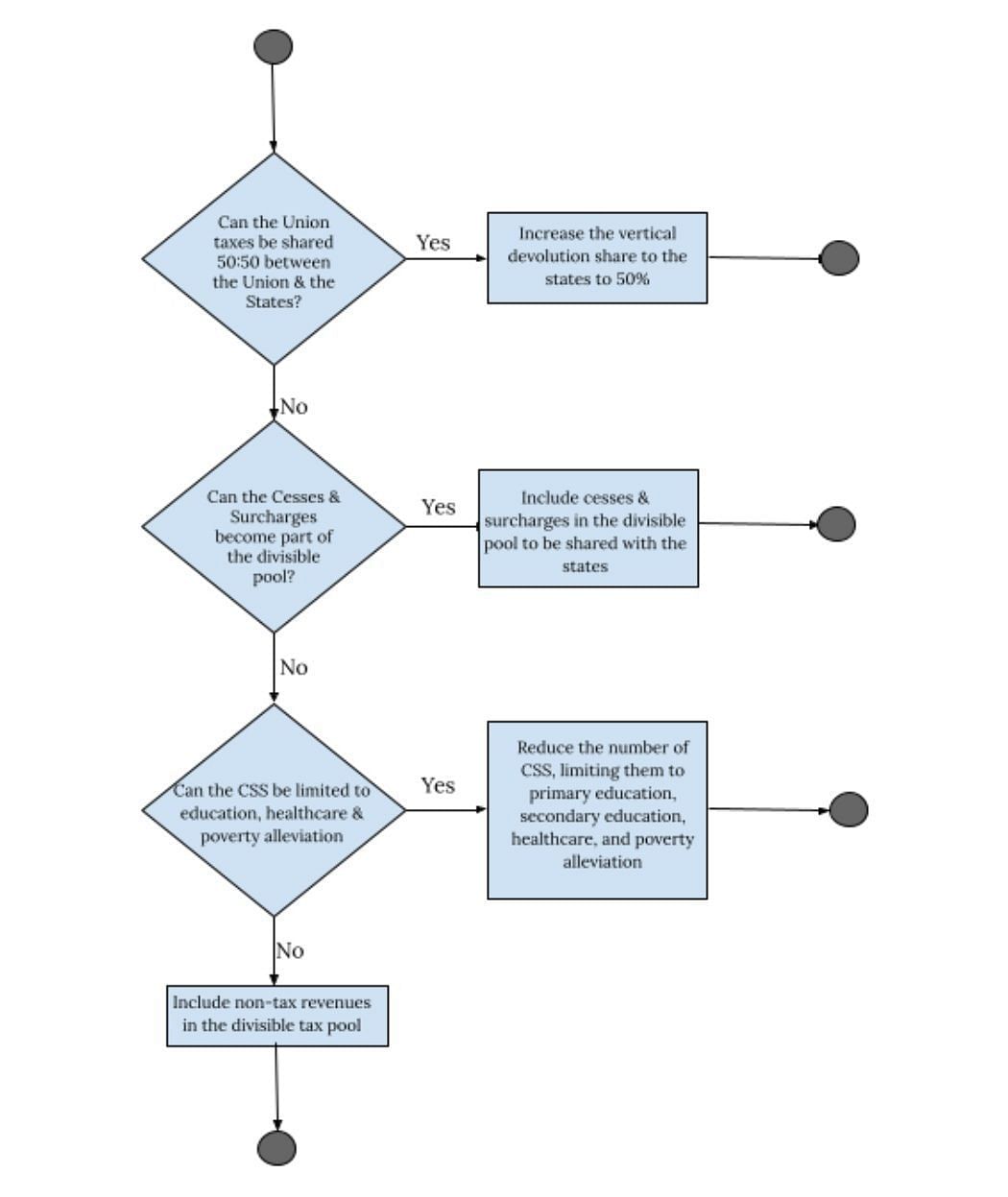

The focus on inter-state sparring on horizontal devolution distracts us from addressing the underlying problem of vertical imbalance. We propose an algorithm that goes to the roots of the problem, as shown in the decision tree below. The solutions are arranged in decreasing order of the fiscal benefits the states receive.

Also read: India’s wicked resource allocation problem has an answer— break UP into smaller states

The way out

The ideal solution would be to increase the vertical devolution share to the states to 50 per cent. This recommendation is not as radical as it may seem; it aligns with what Prime Minister Narendra Modi said when he was the chief minister of Gujarat. Had this option been implemented in FY 2023-24, the states would have received an additional fiscal space of Rs 2.24 lakh crore, increasing the combined revenue pool of all states by 5.42 per cent.

Implementing this change all at once might be difficult for the Union, so a less radical approach would be a gradual increase of 1 per cent per year to ease the transition.

If the ideal solution proves politically unfeasible, the next best option would be to include cesses and surcharges in the divisible pool shared with the states. For the fiscal year 2023-24, the total amount of cesses and surcharges was around Rs 5.01 lakh crore. Including this amount in the divisible pool would have increased the fiscal space for the states by Rs 2.06 lakh crore, raising the combined revenue pool of all states by 4.97 per cent.

If this option also doesn’t succeed, the next-best alternative would be to reduce the number of Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS)—central schemes that are jointly funded by the Union and the states but are wholly implemented by the states. While CSS does augment states’ resources, it has many problems.

For instance, in 2023-24, actual central transfers to states under CSS were Rs 1.12 lakh crore less than the allocated amount of Rs 4.76 lakh crore because many states lacked the capacity to provide the matching funds. The lower absorption capacity, due to weak governance and the low Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) of poorer states, prevents them from fully benefiting from CSS. Beyond these inherent limitations, another fundamental challenge faced by CSS is the Union’s interference in states’ constitutional domains.

Thus, reducing CSS to focus only on early education, healthcare, poverty alleviation, and possibly rural employment guarantee could be a viable approach. This would decrease the expenditure burden on the Union, create more fiscal space, and reduce the need for cesses and surcharges. Limiting CSS to education, healthcare (both preventive and curative), and social assistance could provide states with an additional Rs 1.69 lakh crore, or around 4.09 per cent of their combined revenue pool, which they could use according to their needs.

If none of these options are feasible, the central government must commit to including non-tax revenues in the divisible pool. The Union’s non-tax revenues include interest receipts, dividends and profits from public sector units, and service charges. For FY 2023-24, the Centre’s non-tax revenue collection was Rs 3.01 lakh crore. Sharing these non-tax revenues with the states would have resulted in an additional devolution of Rs 1.24 lakh crore to the states, representing a 2.99 per cent increase in their combined revenue.

While these options might seem mutually exclusive, it is possible to combine one or more approaches. But first and foremost, there should be due recognition of the underlying problem: it is not North vs South, but rather that all Indian states face limited revenue streams for their spending responsibilities.

Sarthak Pradhan (@PSarthak19) and Pranay Kotasthane (@pranaykotas) are researchers at the Takshashila Institution. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)