Indian economy may slowly be recovering from the Covid-induced distress but half of the working-age population is getting left behind. Working women have been disproportionately hit by the pandemic in most countries. And India is no exception.

How wide was the gender gap in terms of employment in India, especially in urban areas, before the pandemic? Will the pandemic increase the gap further even after economic recovery is in full swing?

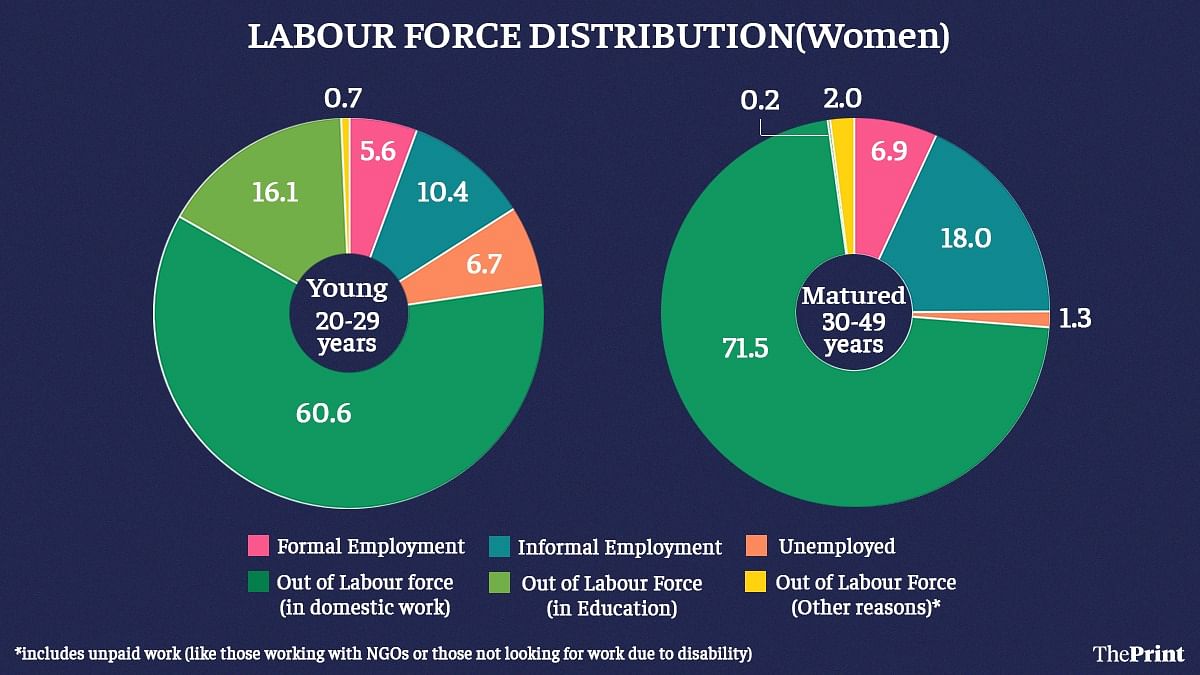

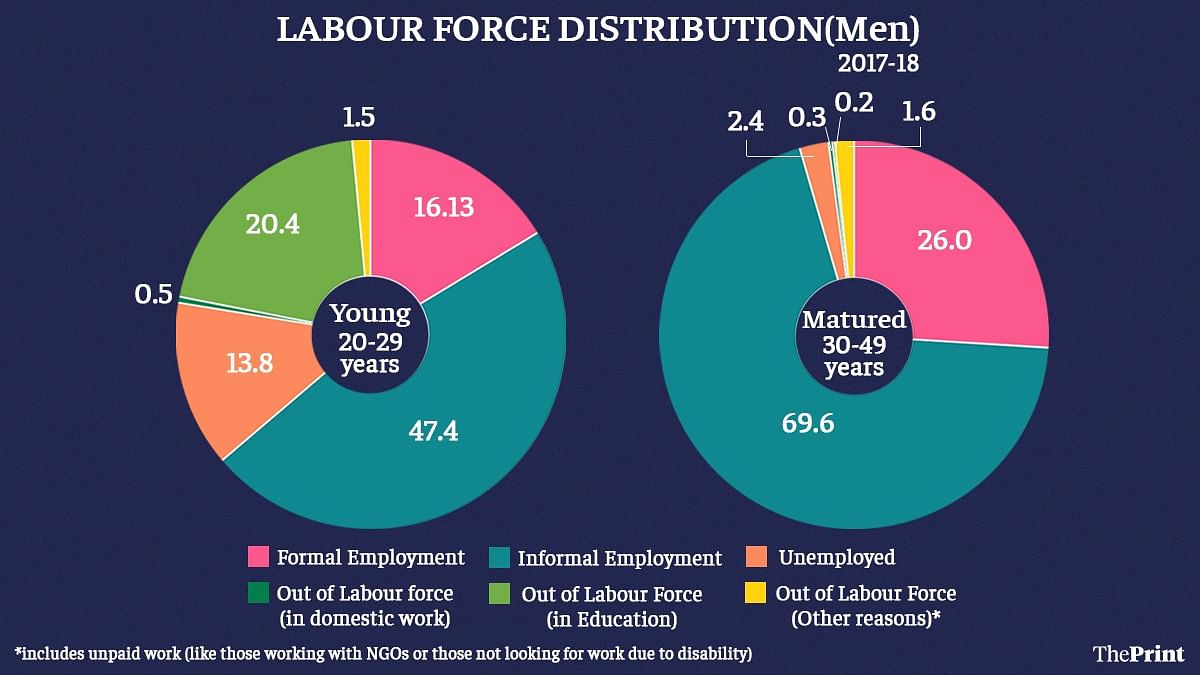

We compare men and women in urban India in two age groups — 20 to 29 years (referred to as young men and women) and 30 to 49 years (matured men and women) to draw insights about their employment patterns. Using data for 2004-05 from the 61st round of NSS Employment-Unemployment Survey and for 2017-18 from the Periodic Labour Force Survey, we divide men and women into those who are employed in the formal sector (a job with a formal contract and social security), those employed in the informal sector, those who are yet to find a job (unemployed), and those who are not looking to work (out of labour force). We further divide the final category (those out of labour force) into those who are in education, those into household duties and those who stay out of the labour market for other reasons such as being disabled.

Also read: Nearly 255 million jobs lost due to Covid globally, signs of economic recovery fragile — ILO

Gender gap in education closing, but not in employment

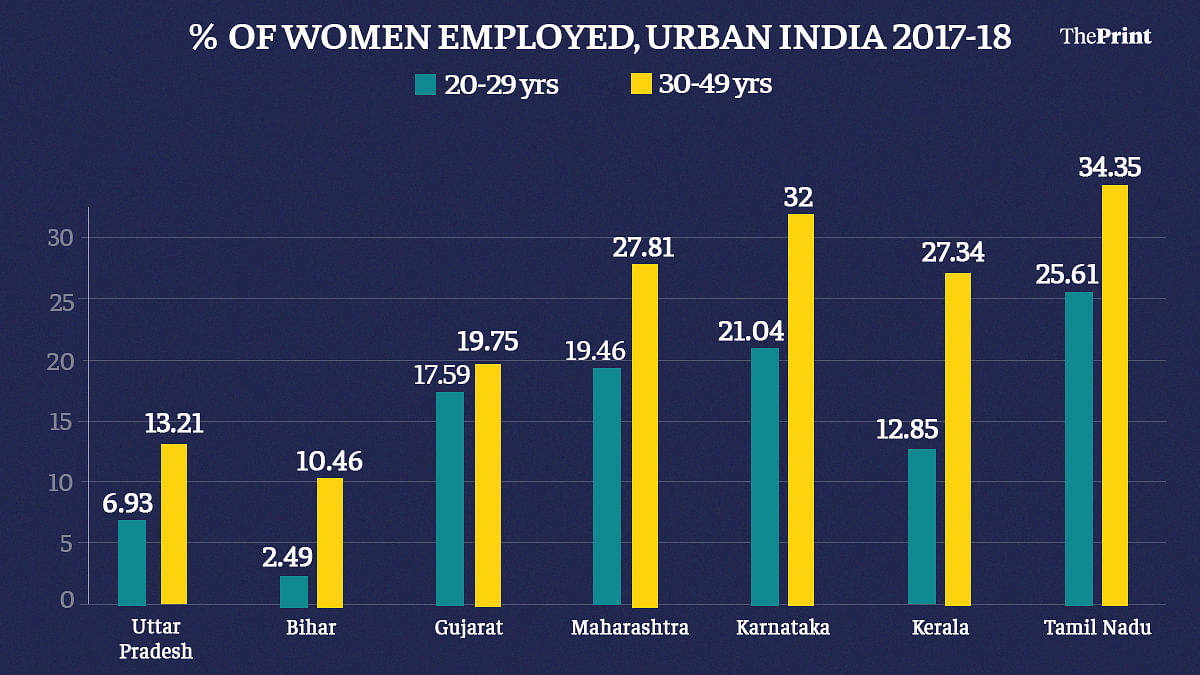

One heartening statistics seem to be that a similar proportion of young men (20 per cent) and women (16 per cent) report being in education. While we do not know about the quality of education, the gender gap in education seems to be narrowing over the years. In contrast, the striking difference is in the share of the employed men and women. Nearly 64 per cent young men, but only 16 per cent of young women are employed. Even in the southern states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, which are progressive in terms of gender equality, only 20-22 per cent young urban women were in paid work.

The reason is well-known – majority of young women, 60 per cent, staying at home to take care of household duties and children. The pandemic has further increased, notwithstanding the help rendered by men, the burden of household and care work on women. Schools and daycare centres have been shut and with all the family members staying at home, the time taken for tasks such as cooking and other household chores has increased in the absence of usual domestic workers.

Not surprisingly, the highest proportion of young women who report being devoted to household work full time are in urban Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. But even a prosperous state such as Gujarat, in its urban centres, has over 70 per cent of women in this category. In contrast, urban Kerala has less than 40 per cent of young women in full-time domestic duty and the highest – a little over 20 per cent into education.

Also read: In India’s job market, women have higher exit rate, lower entry rate than men: Study

Matured men find work…but women stay at home

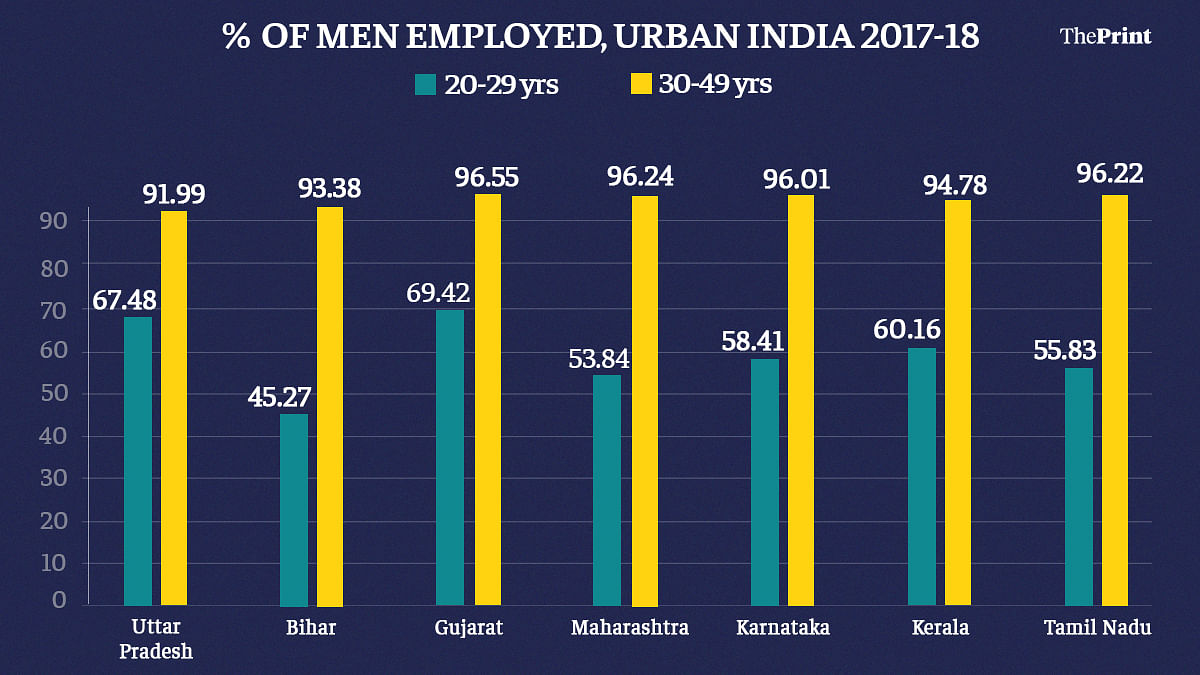

How do the job market outcomes differ for men and women when they are no longer in education and when children are somewhat grown-up? Among matured adults, virtually no one is in education in urban India. Around 96 per cent of men in this age bracket transit into employment with virtually no variation, regionally (see the graph). Essentially, the lack of a social security system for unemployed in urban India and the gender norm that ‘a man should be the primary breadwinner of a family’ seem to force them to take up whatever job that is available.

In contrast, not all women who were into education in the earlier age bracket move into jobs. While the proportion of employed among matured women increases to nearly 25 per cent, the share of women involved full time in household work also increases to nearly 72 per cent. Even in Kerala, the share of matured women involved in household duty increases to nearly 60 per cent. This perhaps suggests that the lack of suitable jobs discourage women and they eventually drop out of the job market. Clearly, barriers to enter paid work such as the inability of women to take up work due to domestic responsibilities, the suitability of jobs and the lower demand for women workers, continue to remain high for women later in life as well.

Also read: More young urban Indian men appear to be studying longer, not looking for jobs: New research

Salaried employment on the rise among young adults

There is one noticeable difference in the employment pattern for young workers over the years. The number of young men employed in the formal sector has doubled to just over 16 per cent in 2017-18 compared to 2004-05. Younger, more educated men now have a higher chance of finding a salaried job compared to 15 years ago. The same is true for women too, but the improvement is not striking given the low share of working women.

Among matured men, there hasn’t been much change in terms of the share employed in the formal sector — 23 per cent in 2004-05 versus 26 per cent in 2017-18. This is also the case for employed women in this age group. This suggests a high labour market segmentation, in that once workers take up and settle into informal jobs, they are unable to transit into the formal sector. If this is the case, it is even more important to improve the chances and ability of younger people to take up their first job in the formal sector.

Also read: Community engagement by ASHA workers behind India’s successful Covid response — WHO panel

Changing gender norms – our homes are key

The gender gap in the employment outcomes in urban India has always been large with significant regional variation. Women are getting more education, which is a good outcome in itself. That, however, is not sufficient to raise their ability to take up employment, if they wish to do so, even post the childcare years. The solution to this socially complex and longstanding issue must begin with attitudinal changes to gender norms around employment and that change must start within our homes and workplaces. Policies that nudge people and firms to change their attitudes would help in accelerating this process further.

This article is the second in the workforce series. Read all the articles here.

Vidya Mahambare is Professor of Economics, Great Lakes Institute of Management. Sowmya Dhanaraj is Assistant Professor of Economics, Madras School of Economics. Sankalp Sharma is post-graduate student, Madras School of Economics. Views are personal.