In December 2019, the Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry released a report on the economic losses in Kashmir since the dilution of Article 370 on 5 August. The sector-wise analysis estimated losses in Kashmir’s 10 districts — not all of Jammu and Kashmir — at over Rs 17,500 crore. The Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry suggested that the estimate, based on J&K’s gross state domestic product was “conservative”. How should we make sense of this figure? Is it a big deal? If it is, why hasn’t this stirred the collective conscience of India?

The J&K government’s 2018-19 estimates put nominal gross state domestic product (GSDP) at Rs 158,688 crore. That means the Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KCCI)’s loss estimate is about 11 per cent of J&K’s economic output. However, KCCI’s estimate pertains only to Kashmir Valley. Even if we assume that Kashmir accounts for 50 percent of J&K’s economy (it is likely more), that means the Kashmir economy has suffered losses of over 20 per cent of its annual output. For any economy, that is a catastrophic loss. Of course, this is not the first such loss reported in Kashmir.

Before anyone accuses the KCCI of exaggeration, let us look at what happened in the aftermath of the Burhan Wani killing in 2016. According to J&K’s Economic Survey (2016), losses between 8 July and 30 November amounted to Rs 16,000 crore. The government provided a sector-wise breakdown of losses as well as the number of working days lost in a place where the working season is already short due to harsh winters.

Also read: India lost at least $1.3 billion to internet shutdowns in 2019

Beyond economic catastrophe

The breadth and depth of Kashmiri suffering go beyond economic catastrophe. But at least economic losses are quantifiable and allow us to create awareness of a genuinely serious problem.

But is it really a catastrophe if it happens and people still go on with their lives, as they did in 2016? An easy way to appreciate the severity of Kashmir’s losses is to compare them with losses due to natural disasters, to which India is no stranger. Cyclones, floods, droughts and earthquakes take a huge toll every year. However, the most expensive natural disaster to have struck any country was the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan. The world watched in horror as we saw the human and material toll of that devastating event.

Estimates of economic losses came in between $195 to $305 billion. If we assume the top end of the estimate and calculate its ratio to the country’s 2011 GDP (nominal), Japan suffered a massive loss of 5 per cent of economic output.

Of course, natural disasters such as the Tohoku earthquake leave scars of those lost in such events. But, the economic losses further devastate the survivors — especially so in poor countries. Just ask Haiti or Nepal in the context of their massive earthquakes in 2010 and 2015 respectively. For Kashmir, losing 20 per cent of its annual output is a huge calamity. That Kashmiris have shown resilience in the face of 30 years of pain, uncertainty, and misfortune doesn’t mean we should normalise their suffering.

Also read: Envoys in Kashmir: Is it just domestic optics or attempt to address global backlash?

Beyond India’s slow growth

The whole country is concerned about India’s slowing economy — 5 per cent growth is reason for despair. This slowing economy has tepid investments, a shortage of jobs, and a sense of foreboding has taken hold. However, we are not talking about declining output here. India’s economy is still growing. Now imagine if India’s economic output were to decline by 5, 10 or 20 per cent, what would be happening on India’s streets? What would the farm sector look like? Would industries be hiring or firing staff? Would investors stay put or flee, as thousands have done in the last few years? Again, what would the streets look like?

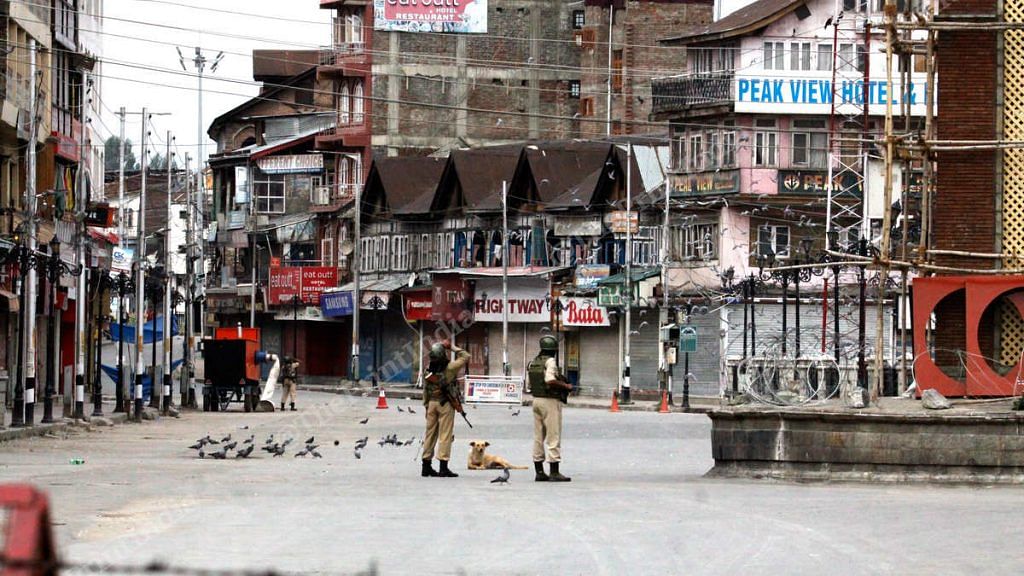

In the midst of such economic devastation, will we hold on to our humanity, our empathetic self? I ask because that is the kind of devastation Kashmir is going through. But it elicits little empathy. Perhaps, Srinagar’s airport road is to blame, which takes tourists through areas where many well-off Kashmiris live. But that is not how most Kashmiris live.

There is a whole other world, where people are eking out a tough existence. Imagine the daily wagers who can’t find work and must feed their families. Imagine the thousands of businesses that can’t pay their staff or keep them on their rolls. Imagine the shikara-walas of Dal Lake or the pony-walas of Gulmarg or handicraft sellers or the hoteliers and their staff and their suppliers. Imagine the orchardists and their rotting fruit or the idling trucks of transporters. Imagine the situation of myriad economic actors.

Also read: With Art 370, BJP hoped to win Kashmir but is now losing Jammu: ‘Are we also anti-national?’

Beyond Kashmir hamara hai

What do you think is the impact of such a massive decline in economic activity?

I spoke to a friend to get a sense of what is going on. His family operates a small industrial unit. At peak operation, the unit employed 45 labourers and staff. Today, the unit is shut. Only two employees, including a watchman, remain. The family has cut household expenses by 70 per cent. I sensed despondency in this usually cheerful person. “Whether you are a business owner or a labourer, everyone is suffering. Only government employees drawing salaries are okay,” he said. He isn’t sure how long this can go on and does not expect much from a government that he feels is uncaring and missing in action.

Kashmir has subsided from memory. A country that benefited from the outsourcing phenomenon, is content to outsource Kashmir’s depression to a careless and brutal government. Why bother looking at open sores when paradise offers a panoply of pristine beauty. Besides, aren’t sad eyes so beautiful? Come to think of it, don’t Kashmiris deserve this? Isn’t it their fault? How can one be empathetic towards ‘anti-nationals’? Let them learn their lesson. This is Narendra Modi’s New India. If you don’t like it, go to Pakistan. Kashmir hamara hai.

It is dispiriting to see where India is today. But, I can imagine Kashmiris looking at the waves of protests around the country and smiling silently and perhaps, with some sadness. While misery loves company, we also know how awful it is to be miserable. But Kashmiris have one thing that makes us formidable. We have gotten used to the idea that the economy, like much else in Kashmir, is about survival. Life will go on. Hum dekhenge.

The author, formerly with the World Bank, is Vice Chairman of the All India Professionals’ Congress (AIPC). Views are personal.