Mumbai: Four years ago I was doing my research for a book on the Hindi film industry veterans. Manoj Kumar was, of course, one of them.

Being a film journalist and critic for nearly three decades, I had access to most contacts—from Yusuf Khan (Dilip Kumar) to Mukri’s daughter, Naseem, who was a regular visitor to Ameen Sayani’s office in Mumbai.

I called up Manoj Kumar’s personal number. As luck would have it, he picked it up. I was lucky as his calls were mostly filtered by a caretaker at home.

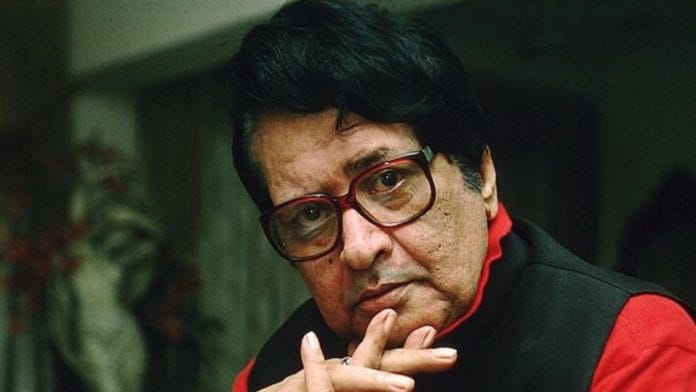

“Namaskar. Manoj Kumar speaking”. I was pleasantly surprised. His voice was sturdy, thick, flawless, and sophisticated with no sign of any ailment. And I knew he wasn’t well enough to meet people.

“Adab!”, I said as I introduced myself and expressed my wish to interview him. He paused for a while and asked in Hindi, “Kya aap mujhe television camera par record karengi?” (Would you record me on TV Camera?) “No! on dicta-phone. I mean a tape recorder,” I replied.

“Theek hai to phir. Tashreef laiye. Khairmaqdam! “ (Fine then. Welcome home).

I was duly impressed by his response in Urdu. I had called him from Delhi.

Cut to Mumbai. He lived in Goswami Towers. The society, huge but unpretentious, didn’t even look like an abode of celebrated actors.

I was accompanied by a friend – an All India Radio Bureau Chief News (English). He wanted to meet Kumar to ask him if he could record for AIR someday too.

I rang the bell and the door opened instantly. “Rana Madam?. Aayiye, Sir aapka intezar kar rahe hain.” (He is waiting for you) A smiling caretaker led me in, joined by Kumar’s wife Sushila Goswami—a writer and a school teacher. A simple woman in a simpler salwar suit, with a smile on her face.

I was escorted to his room. As I entered, I was in for a shock. Kumar was lying on his bed, surrounded by a score of newspapers he was reading and keeping aside. The room had a stench – of a patient perhaps being cleaned frequently after using a bedpan.

The bedsheet hadn’t been changed for some time, it seemed. It would have taken stronger hands to lift him for that. I knew this, having cared for my father who was critically ill. It is excruciatingly painful for someone whose back has almost given up, as Kumar’s had in those days.

His wife must have sensed my shock. She said, “We don’t trouble this child anymore”.

“I love you”, Kumar threw a flying kiss to her, and told me, “She is my best buddy, in the absence of all so-called buddies in the film industry.”

I couldn’t ask him who visits him. He answered anyway, “They call up, but kabhi kabhi (infrequently), you know” and laughed like he had accepted it as his fortune for the times.

I noticed that all the newspapers on his bed were in Urdu. “So you read Urdu?” I asked.

“Arrey Bilkul! I read all Urdu newspapers,” he said and started naming them one by one. “Kya sheerin hai is zaban mein” (This language is sweet).” And he broke into a couplet by Habeeb Ahmad applauding the language: Taaliim-o-tarbiyat mein aham is ka hai maqaam

Sher-o-sukhan ki rooh adab ki ye jaan hai

(This language is prime for education and culture/ it is the soul of poetry and literature)

The mood was set.

A traditionalist

I decided not to make things formal. “So, a Harikrishna Giri Goswami becomes Bharat Kumar in Hindi films and becomes synonymous with Indian nationalism?”

He laughed like I told him a joke. “Actually, Hindi film world typecasts you instantly. I did a few roles of a patriot and I became a Bharat Kumar. Well, isn’t it a beautiful name? So I thought, let it be. But I think I was great as a romantic hero, no?” He looked at us for validation.

We laughed and said, “Of course!” My friend said, “You were the most good-looking and handsome hero of your time. Even heroines had to be beautiful to match up to your good looks.”

He laughed and said, “Thank You. I actually liked myself on screen.” The room was filled with pleasant chirps. The stench was not noticeable. We were served tea and biscuits.

We spoke of the hit films that he directed—Upkar (1967), Purab aur Paschim (1970), Roti, Kapda Aur Makaan (1974), Kranti (1981) and more. He got hooked on Purab aur Paschim.

“Let me tell you something about the role Saira Banu played in Purab aur Paschim,” he said, turning slightly to my side. I was seated on his left, on the bed itself, while my friend was in the centre, on a chair. Kumar rested on his arms, helped by the caretaker who placed two bolsters behind his back for comfort.

The seed for Purab and Paschim was sown when Kumar went to a filmi party, and saw a young girl who looked very comfortable in her short clothes was smoking like a pro.

“ I am a traditionalist and I love Indian culture, and our dresses especially women’s attire – sari and shalwar suit. I kept on observing her manners and by the time I was back home, a film on Indian and Western culture was ready on my mind,” he said, “Now I had to look for that face which would fit that girl’s. After some screen shots, I requested Saira Banu who has sharp features, fair complexion, and was young and wouldn’t look unnatural with those blonde hair wigs and equally classic in Indian saris. For Saira, it was a challenge that she handled so well. You know that the film was a bumper hit?”

“Yes, parents used to show that film to their young children to move away from extreme westernisation. So did ours,” I said.

Also read: Manoj ‘Bharat’ Kumar sang so Sunny Deol could yell—journey of Bollywood patriotism

‘I am not political’

I was struggling to mention politics to him.

“You were born in Pakistan (1937) you came to India. How do you see India-Pak relations or Hindu-Muslim shared co-existence in India?” I asked.

“Hamari Ganga Jamni tehzzeeb ka jawab nahi. We are one. Our film industry is a live example. My film had Pakistan’s Dilip Kumar (Mohammad Ali) and did that role without money, in the name of our friendship.” And he broke into this sher by Kanwal Zia:

Hamara Khoon ka rishta hai Sarhadon ka nahi

Hamare khoon mein Ganga bhi Chanab bhi hai

(We are bonded by blood, not boundaries/ My blood has waters of both Ganga and Chanab (rivers).

I asked, plainly: “But you joined the BJP, which clearly declares that it hates minorities, especially Muslims.

“Who said? Never! I am not a BJP person or belong to its ideology at all. One day, they came to me. Gave a lot of respect. Made me wear an orange colour safa (turban) and a stole. For me, orange is a colour of Sufism and sacrifice,” he said, “What are you saying? I actually was overwhelmed by their love and respect. They felicitated me. Took me to some meetings and that’s about it.”

“I never gave any speech in favour of the party anywhere. I was not aware of any agenda they had. For them, I was a symbol of patriotism, Bharat—the nation, and that is because my films portray me as a nationalist. I am one but in its true way, not agenda-wise,” he nearly started choking with emotions. His eyes went moist.

I was apologetic. I extended a glass of water. He sipped a few drops and said, “Rana jee. Khuda ki qasam, ye politics wale hum film walon ko, hamari image ko misuse karte hain. Mera unsey koi political raabta nahi.” (I swear, these politics people misuse people from the film industry and their image. I don’t have anything to do with them)

“Did you mind me asking this?” I was worried on account of his health. “No no. I just wanted to clarify. Aap media wale hain na. Isko phaila dijiye. (You are media people, spread my opinion).

To pacify him, I recited this to him:

Ab to mazhab koi aisa chalaya jaye

Jis mein insaan ko insaan banaya jaye.

“Right! Ye sher Neeraj (Gopal Das Neeraj) ka hai. I like it.” He had recognised the poet immediately.

Before I took his leave, I asked if I could take a picture with him.

“In this condition? Let’s not do it. Achcha nahi lagta. People see me as a strong man. This could break their heart. I will feel bad too,” he said, and I respected it.

On asking if I could visit him again, he said I was welcome as many times as I wished.

“ I loved talking heart with you,” he said with folded hands. All this while, he was lying down—not a trace of pain on his face.

But I feel the pain, because I know I shall never be able to meet him again.

I must share that after a couple more calls, his family requested that he wasn’t keeping too well to talk or meet. So I stopped calling.

Rana Siddiqui Zaman is a film and art journalist for 28 years. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

Hate minorities really that you ask to manoj kumar and your are proudly declaring.You people would have wiped out entire hindu community just like in Pakistan if BJP didn’t existed .The ganga Jamuna tahzeeb nonsense has to be followed by all not just hindus you get what you give that is the norm .Your clickbait headline shows your hate towards Hindu.stop using a dead man name for your nonsense

The clickbait headline is indicative of the quality of journalism done by Ms. Zaman.

Her insistence on communicating via Urdu and her blatantly communal world view gets amply reflected in this article.