In recent times, the issue of Dalit Muslims’ inclusion in the Scheduled Caste reservation list has sparked controversies and discussions. AIMIM MP Asaduddin Owaisi has not only asserted the existence of Dalit Muslims but also criticised the central government’s opposition to providing reservation to them, framing it as an act of social injustice.

I once supported granting reservation to Muslims and Christians under the SC quota, drawing attention to the persistence of caste-based discrimination across religions in South Asia. However, with the emergence of new facts and insights, I find it necessary to reevaluate my position on this matter.

My initial position was rooted in the aftermath of the high-profile controversy involving Sameer Wankhede, a Mumbai zonal officer of the Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB). Sameer married a Muslim woman, and performed a nikah according to Muslim Personal Law. Former Maharashtra minister Nawab Malik raised concerns regarding Sameer’s Scheduled Caste certificate, arguing that it was illegal for a Muslim to obtain such a certificate, thereby depriving an actual SC candidate of the opportunity. This controversy sparked a political debate, prompting a reassessment of the existing SC reservation system.

Also read: Why plea on ‘reservation for Dalit Christians’ is a dangerous and divisive move

Why I supported SC reservation for Dalit Muslims then

Caste persistence: Caste-based discrimination, including untouchability, is not exclusive to Hinduism but exists across religions in South Asia. It is imperative to acknowledge this social reality and address the discrimination faced by “Dalit Muslims.”

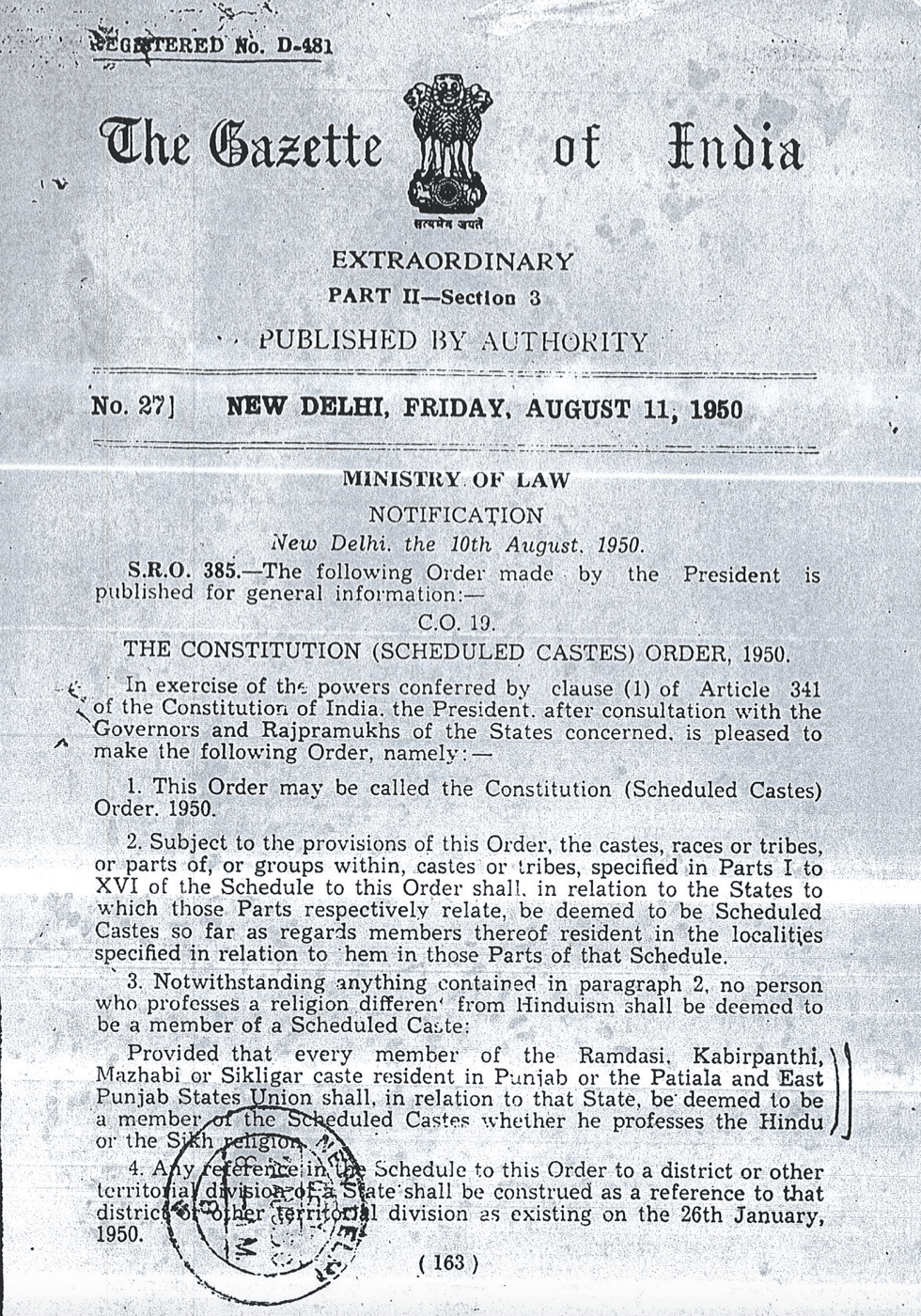

Constitutional contradictions: The Constitution Order of 1950 revoked SC status upon conversion to Islam or Christianity, which contradicts the principles of equality and religious freedom. Denying SC status to Muslim and Christian communities perpetuates religious-based discrimination.

Sikhism and Buddhism: Both the religions, despite not recognising the caste system and untouchability, have included their untouchable communities in the SC category. This underscores the inconsistency in denying the same status to Muslim and Christian untouchable communities, reinforcing discrimination on the basis of religion.

Inclusion in Other Backward Classes (OBC) lists: Muslim and Christian castes have been included in OBC lists at both the central and state levels. This inclusion highlights the recognition of caste identities within these religions, raising questions about the rationale for excluding them from the SC category.

Constitutional basis: Arguments against the inclusion of Dalit Muslims in SC reservation often aim to protect the interests of Hindu, Sikh, and Buddhist SCs. However, such arguments lack a strong constitutional basis. The SC quota is proportionate to the total SC population, and including new social groups would naturally increase the quantum of the SC quota.

Also read: Muslim Dalit Halalkhors are the same as Valmikis. They need legal protection too

Why I don’t support SC reservation for Dalit Muslims now

After delving into recent research and historical perspectives, I have found it necessary to revise my position.

While caste-based discrimination exists across South Asia, untouchability finds its roots primarily within Hindu religious texts. When Muslims and Christians practice untouchability, they are, in essence, contradicting the tenets of their respective religions. Furthermore, the promise made to Hindus who converted to Islam or Christianity was that they would have equal status before God. Given these considerations, the moral claim to SC status for individuals professing different religions is not on equal footing. This raises questions about the persistence of Dalit Muslims as a distinct group despite India being under Muslim rule for centuries, such as in Hyderabad, which prompts us to explore alternative explanations.

A recent research paper by Arvind Kumar, published in the journal South Asia Research, provides significant insights into the historical origins of SC reservations. Kumar points out that the term “Scheduled Castes” emerged in the Government of India Act 1935 and was further defined by the Government of India (Scheduled Castes) Order of 1936. Section 3(a) of this order explicitly excluded Indian Christians from being recognised as Scheduled Castes. The Constitution Assembly debates of 1949 further clarified that individuals who had converted from Hinduism to other religions should not be considered Scheduled Castes. This historical context sheds light on the original intent behind SC reservations and the religious considerations involved. It was my wrong assumption that the SC list was earlier meant to be religion-neutral.

My previous reliance on the Justice Ranganath Mishra Commission’s assertion—that the SC status was initially intended only for those individuals who professed Hinduism—was flawed. Kumar’s research highlights that the 1950 order already allowed for the inclusion of certain Sikh communities.

The Clause 3 first states that notwithstanding anything contained in paragraph 2, “no person who professes a religion different from Hinduism shall be deemed to be a member of a Scheduled Caste”. However, there is then a proviso, which analysts cannot simply ignore: “Provided that every member of the Ramdasi, Kabirpanthi, Muzhabi or Silkgar caste resident in Punjab or Patiala and East Punjab State Union shall, in relation to that state be deemed to be a member of Scheduled Caste whether he professes Hinduism or Sikhism.”

This constitutional order provision was actually a reiteration of the Constituent Assembly debates, accompanied by assurances that safeguards were in place to protect the rights of Sikh Scheduled Castes. The matter of Sikh inclusion in the SC list was not an afterthought but a settled decision of constitution making.

In light of these new insights, it is crucial to reassess the arguments for including Dalit Muslims and Christians in SC reservations. Understanding the complexities of religious identity, historical contexts, and constitutional frameworks is essential in this discourse.

While caste-based discrimination is a concern across religions, it is crucial to navigate the constitutional framework and ensure that any affirmative action policies align with the original intent and legal provisions. This shift in perspective does not undermine the importance of addressing social injustices faced by marginalised communities but emphasises the need for context-specific solutions that uphold constitutional principles.

I concur with Arvind Kumar that:

– The SC list has never been intended to be religion-neutral, as evidenced by the Constituent Assembly debates and historical context.

– The inclusion of backward castes among Sikhs in the SC category was a result of earlier promises and bargaining during the framing of the Constitution and the Partition of the subcontinent.

– Muslim and Christian members of the Constituent Assembly did not engage in similar bargaining for the inclusion of Pasmanda Muslims and Dalit Christians in the SC list.

– Muslim and Christian leaders historically refrained from participating in settlements addressing untouchability, which likely discouraged them from raising the issue of SC status for their communities in the Constituent Assembly.

– The focus of Muslim and Christian members of the Constituent Assembly was primarily on securing religious, cultural, and educational rights, reflecting a different dynamic between Hindus and Sikhs versus Muslims and Christians in postcolonial India.

Dilip Mandal is the former managing editor of India Today Hindi Magazine, and has authored books on media and sociology. He tweets @Profdilipmandal. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)