The much-hyped and politically charged local elections in Hyderabad, the fifth-largest municipal corporation in India, concluded on 1 December 2020. The Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation, or the GHMC elections this year saw an unprecedented scale of campaigning by an array of senior politicians. Despite the hype, the biggest anti-climax was the low voter turnout. The official voter turnout has been recorded as 46.6 per cent, which is consistent with previous years — 46 per cent and 42 per cent in 2016 and 2009, respectively.

Low voter turnout in municipal elections is not a Hyderabad-specific issue. Other bigger cities such as Ahmedabad and Delhi too have been plagued with lower voter participation (40 per cent and 54 per cent, respectively) in their respective local body elections in 2015 and 2017.

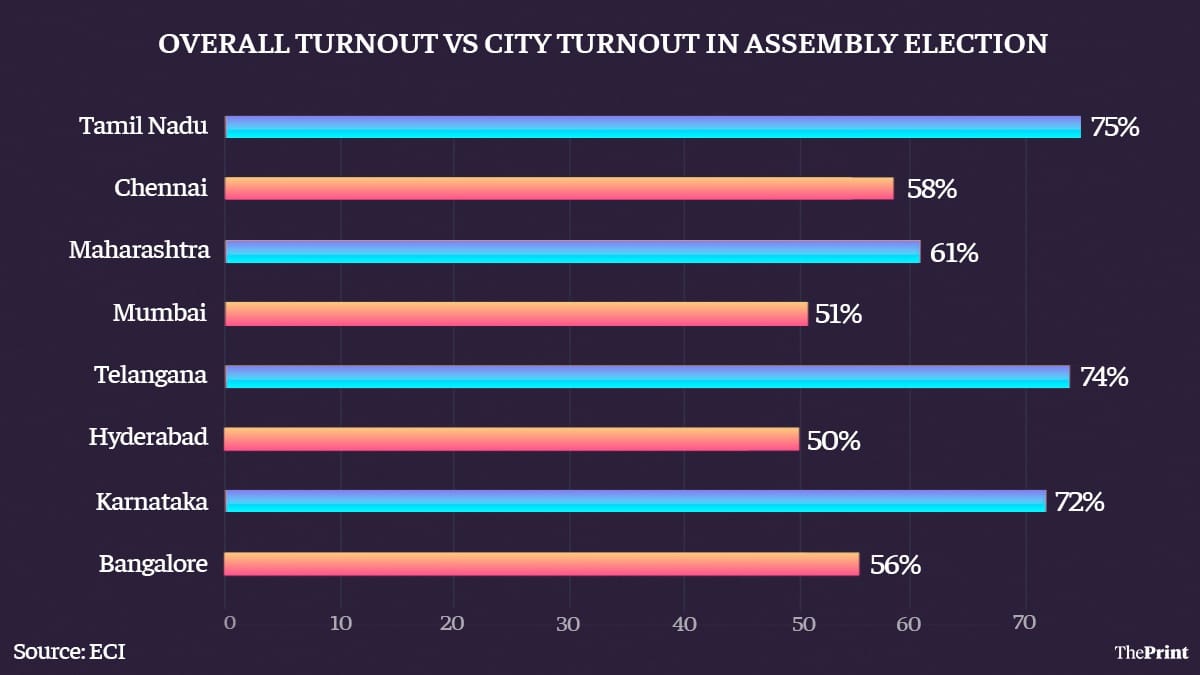

Different reasons have been proposed for this phenomenon. These include voter apathy, which may simply be a lack of interest in city politics. And while this may contribute to low turnout, it is not simply something seen only during municipal elections. Urban centres have often been criticised for not showing up for even state or Union-level elections. The voter turnout in Hyderabad in the 2018 Telangana assembly elections was merely 50 per cent. Overall numbers for the state stood at 74 per cent. This pattern is true of many large cities such as Mumbai, Chennai and Bengaluru. As shown in the figure below, in state elections, there is an average difference of about 17 per cent between the big city and the overall turnout in the state.

A study conducted by Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, Pune, on BMC elections in Mumbai highlighted three factors that are responsible for low voter turnout in city elections: 1) voter apathy, 2) poor quality of candidates, and 3) issues with the electoral management process. The third reason highlights a systemic issue with the voter list management process, particularly for urban centres, which is often under-narrated in the discourse of low voter turnout in cities across elections. In fact, urban centres are plagued by inaccurate voter lists. As cities urbanise at a rapid pace, seeing increased migration, voter lists struggle to accurately reflect the reality on the ground. Work by Janaagraha in Delhi, for example, showed quality issues with the voter list, including up to 49 per cent of omitted citizens and 40 per cent of list entries containing errors of some sort.

While a lot of impetus is given by political parties to amplify citizen participation in elections through campaigns and social media outreach, hardly any effort has gone into leveraging new technologies and making the voter list management process more efficient. It is imperative that this gap is closed to ensure the right to franchise for all citizens, particularly for those living in cities, and pave the way for healthier turnouts.

Also read: Telangana health dept asks politicians, party workers to isolate after Hyderabad campaign

Non-registration of voters

As part of an ongoing research project, Janaagraha is working with Brown University around urban governance, citizenship and service delivery. We are collecting data on participation in elections and reasons for not voting. The data indicates that 39 per cent of all respondents in Hyderabad report they are not registered to vote at all. The numbers are as high as 61 per cent for Mumbai and 46 per cent for Chennai. This proportion is particularly high for citizens living in informal shack settlements in Hyderabad — 58 per cent. If attempts to register are anything to go by, this non-registration is not for want of trying. In Hyderabad for example, 56 per cent of those who were not registered for state/Union elections had actually tried to register.

In addition, out of those citizens who believed they were registered to vote, there were also those who had issues voting in the last municipal elections. For example, out of those who did not vote in the 2016 municipal election in Hyderabad, but believed they were registered, 28 per cent reported not being able to exercise their right because their name was not on the list (at the booth). Moreover, a plurality of citizens (37 per cent) said they could not vote because they did not receive or did not have a Voter ID at the time of polling. Not only Hyderabad, but other cities in the country are also afflicted with similar problems related to non-voting by those who believe they are registered and should be able to vote. For example, even though ‘disinterest’ of those registered to vote is certainly a factor, 6 per cent in Chennai and 7 per cent in Mumbai, a larger proportion in these cities did not vote because their names were not on the list at the booth (Chennai 21 per cent and Mumbai 16 per cent respectively). Or because they did not receive their voter ID (10 per cent and 13 per cent respectively).

Also read: After Hyderabad, BJP targets Kerala local body polls, fields Muslims and Christians

Systemic issues in the voter list management

Understanding issues in the voter list management and infrastructure may go a long way in explaining the hurdles faced by the citizens in registering. The key challenges include:

Voter awareness: Janaagraha’s study in Delhiconducted with over 6,500 citizens across 10 assembly constituencies found that not knowing where and how to register were the top two reasons cited by 7 per cent of Delhi’s 18+ citizens for not having applied for enrolment/correction from their current residence. This suggests gaps in implementation of awareness drives run by booth-level officers and other functionaries through the Systematic Voters’ Education and Electoral Participation Programme (SVEEP).

BLOs: Another study looked at booth level officer (BLO) information and access across 21 of the largest cities in India. BLOs are the frontline workers of the Election Commission of India (ECI) tasked with collecting data on voters as well as verifying their claims and requests to be registered. The study found that BLOs are hard to contact, making it difficult for citizens to get their requests processed.

Out of a total of 9,833 BLO contact numbers tried across 21 cities in the study, only 2,305 could be reached, suggesting that in less than a quarter of cases (23 per cent) was a BLO actually available. Nearly a third of all BLO phone numbers made available by the ECI were either erroneous or did not belong to a BLO, while many numbers simply weren’t listed. Additionally, 51 per cent of BLOs were registered outside their allotted polling part, suggesting they do not reside in the area they are in charge of. Some (6 per cent) reported having to travel more than an hour to reach their PP, restricting their ability to service voters efficiently. Collectively, this indicates there are significant issues in the ‘BLO style’ of functioning.

Also read: Bhagyanagar & Bhagyalakshmi — a 16th-century tale that’s found focus in Hyderabad’s 2020 poll

Registration and data standards

The Delhi (2014-15) study also suggested that over 41 per cent of entries had some error – 21 per cent citizens had moved out of their listed addresses but their names were still present. Indeed, 26 per cent of the city’s 18+ residents were listed in a different polling part (not the one where they resided), with a different address. This indicates that registrations are not dynamic enough to capture citizen movement effectively.

The same study showed that 8 per cent of Delhi’s 18+ citizenry had applied to be on the voter list but were not found on it, suggesting issues in the registration processes and Electoral Roll Management Systems (ERMS).

Our pan-India study found that BLOs were not working as per the ECI’s guidelines and that effective and continuous updation of the lists was not taking place. Furthermore, it was found that data-entry introduced errors on the list. This indicates issues at the BLO level and with the ERMS, in particular with citizen data entry.

The Delhi study found that a large source of errors on the voter list stems from citizen movement from one polling part to another within the same Assembly Constituency (26 per cent). This suggests that if citizens could vote in any polling booth within their assembly constituency, errors would reduce and turnout, increase.

Also read: India’s urban and rural poor expect different things from their local govts, and why it matters

The way forward

It is time that we re-engineer the voter list management process with a greater focus on technology-enabled solutions to ensure every citizen has the right to franchise. For example, automatic voter registration and database linkages can help improve the registration process. Furthermore, this can be enhanced with an improved electoral roll management system with fixed data standards. The BLO role and workflow within this new technology can then be reviewed, adjusted and monitored through a management information system specific to these tasks.

Technology can also be utilised in booth management systems themselves and allow fungible voting across ACs that would facilitate greater turn-out. All this while ensuring citizens are acutely aware of their role in registration and can ably connect with BLOs and others as necessary to fulfil their registration. This can be facilitated through improved information dissemination on BLOs as well as for example, registration drives in partnerships with the employment/education sectors for 100 per cent registration certification.

Katie Pyle heads the Research & Insights team at Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy, based in Bengaluru. Tarun Arora is a Project Manager in the Research & Insights team at Janaagraha Centre. Views are personal.