It occurs so frequently in India that we have given it a name: When lots of people die after consuming contaminated liquor, we call it a “hooch tragedy”.

Over 150 people died in the latest one over the weekend, in Assam’s tea-growing areas around Golaghat and Jorhat. Hundreds more have been hospitalised. Amid street protests, the state government has begun a crackdown on suppliers of illicit alcohol. This incident closely follows another that took place last month in Haridwar district in Uttarakhand and the adjoining Saharanpur district in Uttar Pradesh, which claimed 99 lives.

Indian political attitude towards alcohol is a half-hearted, somewhat guilty acceptance coupled with a strong Gandhian pull towards prohibition.

So, who should we blame for these hooch deaths? The convenient answer is “them” — the unscrupulous people who sell illicit liquor and the inevitable politicians who are somehow mixed up with them. That is, of course, not wrong. But it does not constitute the complete answer, for the liquor mafia is a consequence of India’s moral dilemma on how to deal with the social effects of alcohol consumption. It is “we” who are ultimately responsible.

The Indian policymaker is torn between a relaxed attitude towards alcohol that ends up disproportionately hurting vulnerable segments of society, and tight regulations like Nitish Kumar introduced in Bihar that often create organised crime networks and hooch tragedies. In states where liquor is available, despite high levels of regulation and control, there are recurring calls for its prohibition. In states where liquor is prohibited or highly taxed, there is a higher level of criminality and, at times, hooch tragedy. This is like the famous trolley problem in moral philosophy, wherein you have to choose who dies because of your action or inaction.

Also read: What’s the price of a killer hooch pouch in UP? Rs 25 only

Although our otherwise liberal Constitution, inspired by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and the prevailing sentiment, illiberally exhorts government “to bring about prohibition of the consumption…of intoxicating drinks”, it is a terrible idea. Even Mahatmas can be wrong: Morarji Desai converted Gandhian dogma into public policy and helped create the Mumbai underworld and, eventually, the notorious D-Company, as Hasan Zaidi chronicles in “Dongri to Dubai”. The price of imposing prohibition is hypocrisy, corruption and degradation of moral values of society.

Liquor regulations are a state subject in India, which is a good thing and as it should be. Unfortunately, though, states seldom think of the systemic effects of their policies, creating a complex tangle of licensing and excise regulations that make it hard for firms to operate, and very easy for corruption and criminality to take place. Unscrupulous people seize the opportunity to make money by purchasing alcohol where it is cheap, and smuggling it into places where it is expensive. That is why, for instance, trucks carrying liquor procured in Haryana are being intercepted in Delhi, Punjab and other states. That is also why authorities in Assam complain of liquor being smuggled in from Arunachal Pradesh.

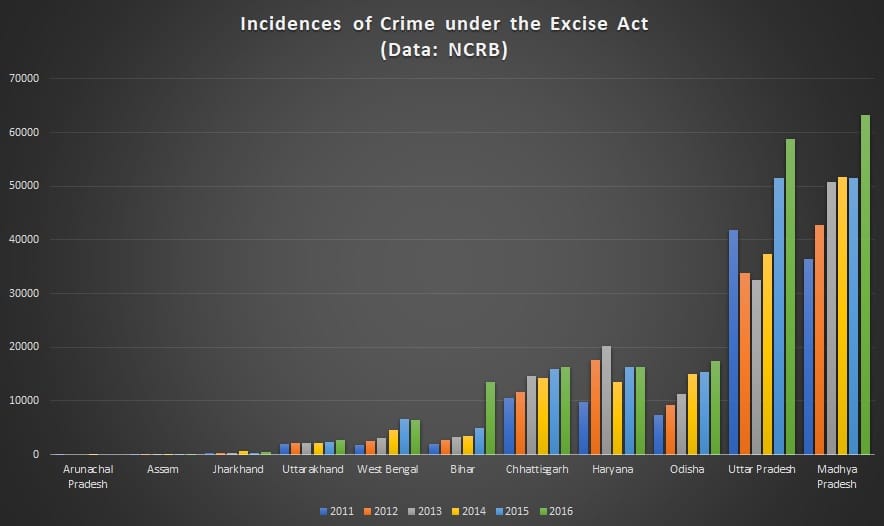

As far as eastern India goes, the imposition of prohibition in Bihar by the Nitish Kumar government in 2016 has created massive incentives for bootlegging. How big are those incentives? Bihar earned Rs 3,142 crore in excise revenues the year before prohibition was imposed. They collapsed to zero in 2016-17. If that market is now supplied underground, there are hundreds of crores to be made. As the chart shows, excise violations in the state, as compiled by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), trebled in 2016.

NCRB data also show that excise-related crimes increased in Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha and West Bengal over 2011-2016, which indicates that a number of bootlegging and liquor smuggling networks are operating in eastern India. With prohibition in Bihar and a 300% hike in excise duty in Madhya Pradesh in over the past three years, illegal liquor industry is not short of opportunities.

Also read: Nitish Kumar’s ISIS-style prohibition moves closer to the end it deserves

It is quite possible that the recent tragedies in Assam, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand can be traced back to bootleg liquor produced in these supply chains. It is not difficult to transport a few hundred litres of illicit alcohol across the boundaries of one or more of these states. Once the supply chain comes into being, a political economy arises around it, with shady entrepreneurs, gangsters, corrupt officials and mixed-up politicians ensuring that the business goes on.

It is naive to believe that the Assam government’s crackdown on smugglers will eliminate the problem. It won’t. Not because of corruption but because the underlying opportunity to run rings around the excise laws of multiple states is still there.

Now, uniform liquor laws across the country would be both economically efficient and drastically reduce inter-state smuggling. This outcome should be achieved through inter-state consultation. Given that excise from liquor manufacturing and sales forms an important source of revenue of many states, it is in their interests to ensure that the industry is governed in a coherent manner. Yet, as long as some states insist on complete prohibition, smuggling and hooch tragedies cannot be eliminated.

Even if regulatory decluttering reduces occurrences of hooch tragedies, the other problems arising from alcohol consumption won’t go away. For that, as Vivek Benegal, professor of psychiatry at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, points out, we need “an urgent shift to a public health paradigm in the approach to alcohol use.” This would entail measures to reduce overall consumption — by raising minimum-age requirements, tightening enforcement of drunk driving, regulating retail and advertising. Along with this, governments must target high-risk behaviours through the public health system.

It is possible to make hooch tragedies a thing of the past, if we can move beyond looking at alcohol policy as a matter of good and evil.

Also read: Why the women’s march for prohibition in Karnataka was bound to fizzle out

Nitin Pai is director of the Takshashila Institution, an independent centre for research and education in public policy.

The cheapest brands of country liquor should be affordable to the poor. That would become possible if state governments sacrifice excise revenue. Prohibition, of course, is an invitation to such tragedies.