This week, India is celebrating the auspicious Navaratri, the nine nights of Hindu Goddess Durga. While popular all over India, Durga is perhaps most fiercely beloved to Bengalis; the Bengali diaspora across the world set up pandals to worship her for Navaratri, and Bengali culture, music, and cuisine are celebrated both within and outside these temporary shrines.

But where did the goddess Durga originate? How did she grow so beloved to Bengalis in particular? The answer takes us through nearly 2,000 years of South Asian history—from Zoroastrian and Roman iconography in 2nd century CE Mathura, through generations of warlike medieval kings and merchants, to Mughal-ruled zamindars in early modern Bengal.

A goddess of war

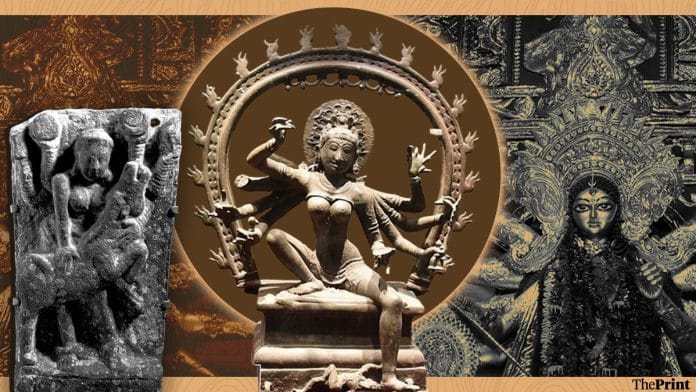

As with many of South Asia’s most popular gods today, it’s not possible to pinpoint the beginnings of Durga. Fierce goddesses are present in the Vedas, the most ancient of our religious texts, but they aren’t battle goddesses and buffalo slayers like Durga. The earliest depictions of her in sculpture, though, come from an entirely unexpected place: one of the major cities of the Central Asian Kushan empire, Mathura, in the upper Gangetic Plains.

In Heroic Shaktism: The Cult of Durgā in Ancient Indian Kingship, historian Bihani Sarkar (perhaps the most interesting scholar of Durga today) writes that Kushan-ruled Mathura has yielded dozens of Durga statues, a concentration seen nowhere else in 1st-2nd century South Asia. Intriguingly, these early depictions of Durga had much in common with the royal Kushan goddess Nana, a Zoroastrian deity whom the Kushans believed granted them kingship. Durga, like Nana, is depicted with the Sun and Moon, seated upon a lion. In some cases, she is shown killing a buffalo by grasping it from behind and cutting its throat—oddly reminiscent of the Roman deity Mithras, popular in the Mediterranean world at the time. Like with other Hindu deities, the global contacts of the Kushans may have offered a rich visual canvas for devotees of Durga to draw from.

Over the next centuries, Durga’s following grew steadily as various royal religions sought to absorb her. The worshippers of Vishnu considered her Nidra-Maya, a deity of sleep and death, embodying the yogic sleep of Vishnu. But gradually, Shiva worship grew to become South Asia’s dominant royal religion. In Shaivism, Durga was linked with the fierce aspects of Parvati, Shiva’s consort. She was associated with battle, the founding of cities, and salvation from crises. Sanskrit hymns were composed, praising her prowess in war and her extraordinary beauty.

Sarkar (Heroic Shaktism) suggests that, to newly-emerging Shaivite states of the early medieval period (6th-12th centuries), Durga represented civilisation, on its frontier with the anarchic, terrifying world of forest peoples, war, death, and disease. Think of her as the medieval Indian analogue of Colombia or Marianne, the feminine representations of 19th-century America and France respectively. But unlike Colombia and Marianne, Durga had an amazing ability to absorb diverse local goddesses beyond the pale of urban respectability, who represented—like her—grit and blood, magic and divine favour, which medieval people believed held up society. From Stambheshvari, the deity of the Odisha hills, to Vindhyavasini, the dweller of the central Indian mountains, to Korravai, the warrior-maiden of the Tamil coast—all came to be associated with Durga.

Throughout the medieval period, while kings routinely worshipped male gods with ever-more refined and sanctified offerings, Durga was generally offered blood, flesh, and heads—both animal and human. Sculptures and inscriptions from across South Asia attest to this. It wasn’t just kings and warriors that held her sacred: even medieval Tamil merchants claimed to be “beloved sons of the goddess Durga” and named their towns after her. On the west coast, a 10th-century Muslim port governor, working for a Shaivite emperor, patronised Durga—possibly holding her responsible for his naval victories. For centuries, Durga was most importantly a goddess of battle and viscera, a role that she has substantially lost today.

Also read: Tirupati god was originally offered pongal. North Indian pilgrims brought laddus

Toward a goddess of harvests

From the 12th century onwards, new modes of political power were violently established in the subcontinent. Generally speaking, this new Indian Muslim kingship legitimised itself through association with Sufi saints who claimed direct communion with the divine, rather than offerings to gods. And of course, Muslim kings were happy to attack older royal temples, some of which were associated with Durga. Indeed, as the Delhi Sultanate was being established, at least some Hindu rulers buried their images of Durga, hoping that she would someday rise and help them overthrow the “barbarians”.

Of course, this iconoclastic attitude did not hold true for all Indian Muslim kings. For example, as Sarkar writes in her paper ‘The Rite of Durgā in Medieval Bengal’, the 15th century Bengal Sultan Jalal-ud-din patronised the Brahmin Brihaspati Rayamukuta, who composed Sanskrit texts on Hindu deities. Jalal-ud-din also deliberately used a lion motif on his coins, since it appealed both to worshippers of Durga and Persianate audiences. Since Durga could no longer be the premier royal war goddess in a Sultanate-dominated world, Sanskrit texts from the 15th century stopped asking her for military success. Instead, they asked her for wealth, sons, fertility, and good harvests, reflecting the interests of a new kind of patron—the great Bengali landholders, or zamindars. She was also praised, increasingly, as Annapurna, the goddess of endless rice.

Across Bengal, according to Sarkar, Durga was worshipped in many forms, with many local rites. But the zamindars’ reinterpretation of her as a goddess of harvests and bounty proved most influential. The zamindars generally collaborated with the Mughal conquerors of Bengal, who arrived there, led by the Rajput general Mansingh, in the 16th century. Yet Durga offered them a route to insist on their proud traditions and link them to older ideas of kingship. In a slightly later text, the Annadāmaṅġal of Bhāratachandra, the invading Mansingh, impressed by various miracles, is initiated in the worship of Annapurna by a Brahmin zamindar.

However, the emperor Jahangir scorns Annapurna and imprisons the Brahmin. Enraged, Annapurna and her hordes of ghouls ransack the zenanas and palaces of Mughal Delhi, until Jahangir pleads for mercy. Pleased, she grants him a vision of all her Puranic exploits, at which point he worships her and enjoins the Muslims of Delhi to do so as well.

Mughal rule over Bengal ended, but the zamindars endured into the colonial period, moving to Calcutta and Dhaka. This was the latest and most recent step in Durga’s evolution, as she now became a neighbourhood goddess, supported by community donations instead of royal largesse. Though now a benevolent mother more than a fierce warrior, Durga has outlasted innumerable empires, and will probably outlive us all.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)