India is a rising power and seeks to protect its widening interests and advance its influence in international affairs. Can India’s foreign policy deliver on its greater ambitions? The answer to that question in part depends on an assessment of the present strengths and weaknesses of the Indian Foreign Service and Ministry of External Affairs.

Using the policy capacity conceptualisation and framework developed by Xun Wu, M. Ramesh, and Michael Howlett, the paper examines the analytical, operational, and political competences of India’s foreign service at three levels – the individual, organisational, and systemic.

Does India have the foreign policy capacity commensurate with its rising power ambitions?

We note the judgment of former Foreign Secretary and National Security Adviser Shivshankar Menon, based on his reconstruction of five key foreign policy choices since the early 1990s, that “India has serious capacity issues in the implementation of foreign policy and lacks the institutional depth to see policy through”. Menon argues that India has shown “boldness in policy conception, caution in implementation”. He traces implementation problems to centralisation of decision-making, lack of “capability” in the foreign ministry, weak “institutionalisation of foreign policy implementation”, and serious “capacity issues”.

Based on our audit of Indian foreign policy capacity, we argue that the IFS and MEA have strengths in terms of the individual level competences of its officers but also a range of weaknesses particularly at the organisational and systemic levels, the most tractable and remediable weaknesses being at the organisational level.

Also read: India has gone truly global so why is its foreign policy so outdated

Assessing the individual level

As the face of India’s overseas diplomacy, IFS officers are tasked with promoting their country’s national interests abroad. We assess their capabilities using three key variables: the analytical capacity of officials (their knowledge and techniques); the managerial and leadership skills of officials; and the political knowledge and experience of decision makers including their understanding of the interests, ideas, and ideologies of other political actors.

Analytical capacity of officers

There is evidence that the skills of IFS officers are of a high level, comparable to counterparts in the diplomatic services of bigger powers and more advanced economies. This is attested to by foreign and Indian diplomats. Their judgment is that IFS officers work extremely long hours and are under enormous pressure in dealing with myriad responsibilities but are professionally impressively competent.

Managerial and leadership skills of the officers

Softer managerial and leadership skills are essential for IFS officers, and they are often quickly acquired in the rather challenging work environment at home but perhaps even more so in Indian embassies abroad. Given chronic understaffing, many overseas missions are led by only an ambassador and one or two diplomatic-rank officers. This allows officers overseas much greater room for initiative.

Individual political knowledge/experience of dealing with political actors

IFS officers bring solid political knowledge and experience to their work including an understanding of the interests, ideas, and ideologies of political actors at home. Their stints in New Delhi or in the embassies brings them into frequent contact with Members of Parliament (MPs), Members of Legislative Assemblies (MLAs), state ministers including chief ministers, and central ministers.

Also read: Modi’s international activism apart, India’s new govt will have foreign policy challenges

Assessing the organisational level

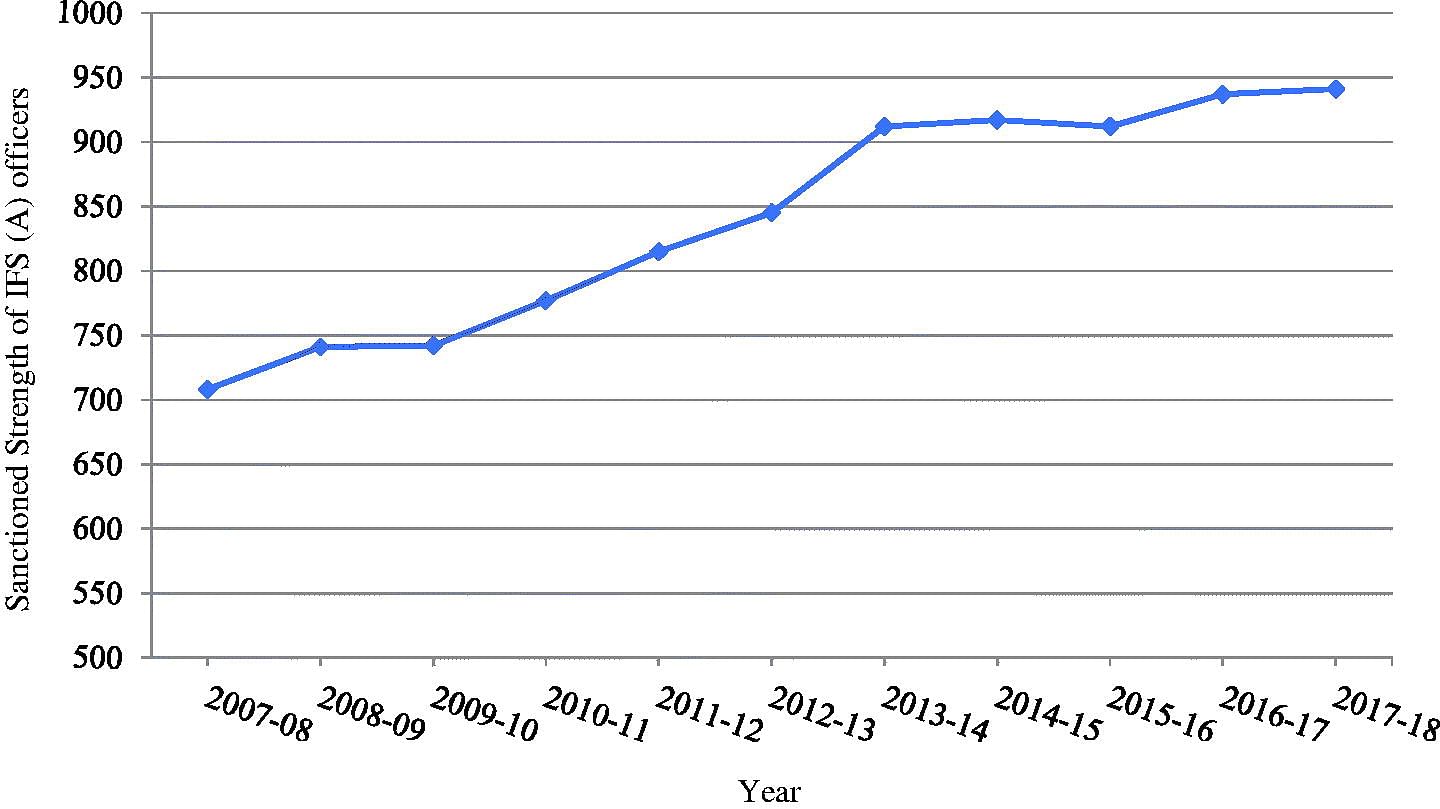

Among the organisational variables affecting policy capacity, Wu et al. suggest the following: critical mass of capable officials and the infrastructure for collecting and processing information; the internal organisation of public agencies and particularly their internal cohesion; the relationship of a policymaking organisation with political institutions; and learning and communications with governance partners and the public. Our assessment suggests that contrary to individual level competencies and skills, Indian foreign policymaking is marked by serious organisational deficiencies, the most serious being insufficient cadre strength which continues to be inadequate:

Sanctioned strength of IFS (A) officers from 2007 to 2017

Assessing the systemic level

Foreign policy capacity is also problematic at the systemic level. Here, factors such as the general state of knowledge and educational capacities/facilities in society at large on foreign policy issues, coordinative capabilities between MEA and the private and public sector, and people’s trust in political, social, economic, and diplomatic processes and institutions are relevant.

On systemic competences, the picture is quite mixed. The general awareness and knowledge of international affairs in the wider public is quite low. The education sector, including policy institutes, is also quite weak in producing high-quality international studies’ teaching and research. In addition, MEA’s partnering with businesses and NGOs is quite “thin”. Finally, in contrast to the rather gloomy picture on public awareness of foreign policy and international relations and partnerships, public trust in the government appears to be relatively high compared to other societies – though evidence in this regard is scarce and open to question. Foreign policymaking being remote from the lives of most ordinary citizens is probably better shielded from feelings of mistrust than virtually any other policy sector.

Conclusion

The Wu et al. framework provides a way of systematically assessing Indian foreign policy capacity. Our analysis suggests that of the three levels of capacity, individual level competences are relatively strong, judging at least by the abilities and morale of IFS officers. The organisational and systemic level competences are weaker, with significant deficiencies and lacunae. Systemic level change will be slow and challenging, given the range of actors and processes that require change – from creating greater foreign policy awareness in India and reform of international studies’ teaching and research to increasing the level of trust in government. Trust building is a complex process that resides at the heart of the political system and is deeply connected to nature of political culture.

The organisational level features various weaknesses and lacunae. These are more tractable, and reforms should begin at this level. A key organisational reform is to reduce the extremely hierarchical nature of the top leadership at headquarters. At the same time, MEA needs to develop stronger ties with related government ministries, particularly the economic ministries, the Ministry of Home Affairs (which deals with issues such as visa issuance and internal security), and, above all, the Ministry of Defence. MEA also needs to improve communication with other agencies but even more so with Indian and foreign businesses and civil society at home and abroad. The most pressing reform at the organisational level, however, is to address the severe shortage of foreign service officers by dramatically increasing recruitment: foreign policy is not quantum physics, and training and socialisation of recruits can be rapid.

Also read: What IFS Jaishankar’s speeches reveal about Minister Jaishankar’s roadmap for India

Foreign policy capacity requires investment in long-term and deeper study of strategic challenges and instruments. In particular, MEA needs a stronger and more dedicated scenario planning unit. A larger service would allow more officers to be dedicated to scenario planning functions. It would also allow officers to take sabbaticals and refresh their skills, with stints at universities and think tanks or even with businesses and NGOs.

There is no absolute standard of policy capacity. In the end, all policy capacity is relative: over time; compared to the quantum deployed by other governments; and in relation to one’s goals and ambitions.

Our finding that foreign policy capacity is relatively strong at the level of individual competence and relatively weak at the organisational and systemic levels may provide an answer to why India thinks creatively but implements poorly. Talented and skilled individuals can evidently think imaginatively in response to India’s external challenges; but organisational and systemic constraints lead to watered-down implementation. This is not an unfamiliar lament in public policy studies – the gap between conceptualisation and implementation. It may well be the story of Indian foreign policy capacity and effectiveness.

Kanti Bajpai is Wilmar Professor of Asian Studies and Director of the Centre on Asian and Globalisation, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.

Byron Chong is on the research staff of the Centre on Asian and Globalisation, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.

This article is based on the authors’ paper, ‘India’s Foreign Policy Capacity’, published in the journal, Policy Design and Practice. The paper can be accessed in full here.

There is no doubt that MEA has no dearth of outstanding and hardworking diplomats but the problem is, as in other government Ministries and departments, it also suffers from hierarchy, connections and elitism. It has not kept itself up with progressive and forward looking forces within New India. It still considers itself as exclusive club of few privileged persons and is not ready to accept that, as in other civil or central services, many distinguished and intelligent persons from less privileged and rural backgrounds are joining diplomacy. It continues to give precedence to privileged and connected officers than to performing and hardworking officers from humble backgrounds in overseas postings and headquarters deployment. It’s high time that it awakens and understands changing reality and adjusts its composition from being exclusive to inclusive.

True. I also heard these things. Many people say that there are few Ambassadorial or Consular posts where only S.C./ST /OBC diplomats are posted. If you see the parliamentary answers related to postings of S.C./ ST, you will find that there are certain stations where the ambassador or consul generals belong to backward category only are posted. Seems like pattern. How come MEA earmarks and decides these postings. Despicable in the era of freedom and equality and blot on largest democratic country. MEA should decide on performance and output irrespective of category. Everybody in civil service is equally patriotic and loyal to nation, there should not be any question of

Caste, class, region and religion.

Hope that PM, who is champion of marginalised, will do something about it and reform MEA from inside out.

We need a long term bipartisan and critically developed vision for India (given the diversity of peninsualar, central, north eastern and northern parts) and use foreign policy as a strategic and tactical tool to build a stronger, benevolent and mutually beneficial relationships. Extending the Arthasastra principle (“No man you transact with will lose; then you shall not”) beyond economic activity may be a good start. IFS officers are at the end of the day should be historians with ability to see the future in the context of the past and present, and stay away from consular work, and focus more on social contracts between nations and group of nations. People to people movement and cultural exchanges can help anchor such relationships, and have greatly benefited us in the past. However, doubt the current govt has the ability for give and take beyond economic activity as it sees any cultural exchange as a threat to its narrow version of Hindutva and the great Hindu nation, a fallacy and disservice to this great region of federal states.

One issue this column does not address is how far IFS officers are able to influence the basic thrust of foreign policy formulation. We are not concerned merely with consular functions, how elegantly our missions abroad project the image of India. Is their collective knowledge, expertise, institutional memory the driving force, or do they simply implement decisions taken above their level.