Lapses and gaps in the investigation process covered all aspects of the Hashimpura case.

The Delhi High Court’s verdict in the case involving custodial killings in Hashimpura over three decades ago is an important moment for the rule of law in India. It reminds us of where things stand.

India’s criminal justice system is notoriously broken, and no systemic reform is in sight. Countless reports of police reform lie untouched, the capacity and functioning of trial courts is a matter with no short-term political rewards, and most elite actors who have the power to initiate change in the system – across the legal and political domains – have little interest in initiating such change. The age-old secret of Indian legal reform has been that no actor capable of enabling reform has a stake in doing so, and the criminal justice system exemplifies that tragedy.

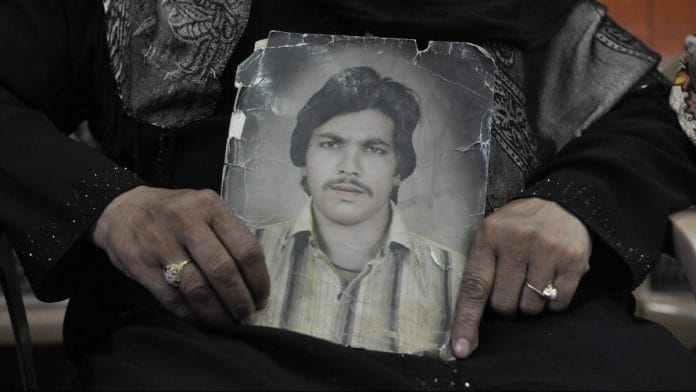

The facts of the Hashimpura case are familiar, perhaps even all too familiar. The month during which the event occurred – May 1987 – had witnessed communal riots, the posting of security forces, and the arrests of hundreds. The Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC) rounded up 42-45 Muslim men and shot them at sight. Only five survived. FIRs were filed, the case was transferred to Delhi, a trial took place where all the accused were acquitted. When the acquittal judgment was delivered by the lower court, it had been 28 years since the event.

Also read: What’s a life sentence when life is almost over: Hashimpura victims’ kin on court order

The key fact that shaped the trial court’s verdict was the connection between the identity of the persons and objects involved and the crime — the identity of the truck (in which the victims had been abducted before being killed), the identity of the victims, and the identity of the accused. The Delhi High Court’s consideration of additional evidence, such as register entries, was able to fill some of these missing gaps, and its careful perusal of the forensic evidence was able to explain a number of factors that had shaped the acquittal in the lower court.

The facts outlined in the judgment of the Delhi High Court provide a fascinating if horrific window into the state of criminal justice in India. For example, a judge in Ghaziabad tried to issue warrants against those who were accused no less than 23 times but had no success in doing so; documents that were in the possession of the State of Uttar Pradesh were not provided to the investigating agency. The Delhi High Court put the matter somewhat subtly when it asked, “How the State of UP managed to have the records of a pending criminal trial weeded out is indeed a mystery”.

The lapses and gaps in the investigation process covered all aspects of the case. Important material object such as the truck was not seized in time, allowing it to be “washed clean of any evidence including chemical residue, blood, grazing caused by bullet marks by the accused persons”. Further, elementary inspections were unperformed. For example, two scenes relevant to the crime (the village of Makanpur and the site near the Hindon canal), which were crucial to the corroboration of witness statements and to the recovery of evidence, were not properly surveyed and investigated. The Delhi High Court’s indictment of the criminal justice process was severe. The court went so far as to note that “this is a case where it has been actively attempted to destroy the evidence by the police themselves”.

Also read: Delhi High Court sentences 16 ex-cops to life imprisonment in Hashimpura massacre case

Importantly, the court noted that events such as these were best understood as custodial deaths. Although the victims had not been killed in a confined space, they had been detained without their consent, forcibly transported to a location, and not allowed to escape. This was, as a result, a case of custody, which was beyond the limits of the law, and death in such situations must be understood as a custodial death. This observation was crucial, as it understands the idea of belonging in custody not merely as the four walls of a police station but rather a space where one is involuntarily placed under the authority of the police.

Though the Delhi High Court verdict is noteworthy, the court was only too aware that its verdict is a case of “too little, too late”. More than a victory for the families of the victims, this judgment recognises the overall tragedy of the situation. Though the court did what it could, remarkable delays and unconscionable lapses in investigation must have made the verdict seem somewhat without meaning for the people who were directly involved.

Also read: In 2017-18, there were 5 custodial deaths per day in India, says report

Even though the systemic failures of India’s criminal justice system were sharply underlined, nothing remains as disturbing as the brutal facts of the events themselves. These two sentences perhaps best capture that: “In the present case, the victims were last seen alive when they were taken away in the truck by the PAC. The next thing heard of them was when their dead bodies were recovered from the canals.” These lines are easily written, but the real question is whether anyone who matters is listening.

Madhav Khosla, co-editor of the Oxford Handbook of the Indian Constitution, is a junior fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows.

Modi will win 2019 election due to support from Rahul Gandhi. The more he speaks, modi prospects improve.