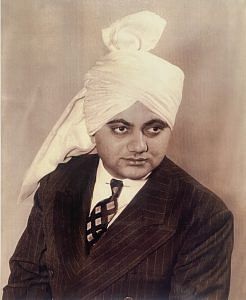

An alumnus of MK Gandhi’s Gujarat Vidyapith, Rabindranath Tagore’s Visva-Bharati, New York University, and Columbia University, Krishnalal Shridharani was a reputed Gujarati poet, playwright, journalist and author. His thesis on Gandhi’s satyagraha became the “gospel, bible” for many African American activists during the United States’ civil rights movement.

The first turning point of Shridharani’s educational journey was his entry into the nationalist, non-conventional Dakshinamurti school at Bhavnagar at the age of 11. Then, when he was just 16, a high-brow Gujarati literary monthly, Kumar published his first poem.

Inspired by Gandhi, Salt March

Born in Umrala in 1911, Shridharani joined Gujarat Vidyapith in 1929 and was a part of the youth brigade named ‘Arun Tukadi’ in Gujarati during the famous Salt March to Dandi led by Gandhi. The young brigade, including Shridharani, was instructed to travel ahead of Gandhi and fellow marchers to make necessary arrangements at villages on the march’s route. Shridharani’s poem on the Salt March, called Sapoot, was a part of Gujarati school textbooks for a long time. He also witnessed the midnight arrest of Gandhi at Karadi on 5 May 1930, barely a month after the successful completion of the Salt March on 6 April 1930.

Mass arrests followed the Salt March. Shridharani was also arrested and sentenced to jail for three months, first at Ahmedabad’s Sabarmati Jail and later to the jail at Nashik. The dehumanising environment and experiences of fellow prisoners moved and inspired Shridharani to write a short story and a drama in Gujarati titled Insaan Mita Dunga (1932) and Vadalo (1930).

British rulers found his drama for the 100th issue of Kumar objectionable and proceeded to ban it. Security of Rs 2,000 and a written undertaking was sought from the editor, Ravishankar Raval. But Raval continued publishing Shridharani’s poems without informing him of the incident, revealing it much later.

Shantiniketan was the next destination for the non-conventional education spree of Shridharani. It exposed him to a world that extended beyond national borders. He came into contact with American teachers at Shantiniketan and nursed the dream of going to the US for higher study. He had no resources to realise his dream. But Prabhashankar Pattani, the dewan of Bhavnagar state, awarded him a scholarship on the recommendation of Tagore. Shridharani left for the US in 1934. By then, he was already known as a bright young poet and writer in Gujarati.

Also read: Amarsinh of Rajkot—1st Indian cricketer to play professional league cricket in England in 1932

War Without Violence

Shridharani completed his A.M. from New York University (1935), M.S. (1936), and Ph.D. (1940) from Columbia University. The subject of his doctoral dissertation in sociology was an analytical study of Gandhi’s satyagraha. It was published under the title War Without Violence. It influenced African-American intellectuals and activists of the civil rights movement in such a manner that the activist Bayard Rustin called it “our gospel, our bible.” It was widely discussed.

African-American rights activists A. Philip Randolph, Rustin, Pauli Murray, and James Farmer were hugely influenced by Shridharani, according to Malathi Michelle Iyengar, who did her PhD at the University of California and published a dissertation titled Learning to Remake the World: Education, Decolonization, Cold War, Race War (2017). Layla Varkey, a master’s student from Columbia, discussed Shridharani’s role in spreading Gandhi’s action-oriented philosophy in the US in a podcast hosted by the Ambedkar Initiative of Columbia University.

According to Varkey, Shridharani “took the mysticism out of Gandhianism and instead provided a Gandhi of pragmatic action or realpolitik.” She also mentioned Harlem Ashram, “which was an experiment in interracial pacifist living at 125th Street and Fifth Avenue that existed from 1940 to 1948.” Shridharani was closely associated with it.

Shridharani’s other book, My India, My America, published in New York in 1941, was a tongue-in-cheek analysis of both countries, their customs, and people.

While talking about child marriages in this book, he quipped, “I wanted to be a good Hindu, always, but of the year 1925 a.d., not 1925 b.c.” He also wrote of Indian candidates failing in the Indian Civil Services (ICS) exams who “seek the solace of the Inner Temple, to be called to the Bar. The result is that there are more “barristers” than ambulances in India.” Comparing the examination system in both countries, he wrote, “In India, examinations are given to find out what the student does not know, while in America, they are used to discover what he knows.”

After spending 12 years in the US, Shridharani returned to India in 1946. He soon realised things had changed drastically back home during his absence. In this period, he resumed his writing in Gujarati and wrote a memorable poem, Aathmu Delhi, a satirical take on the city’s mythological, historical and cultural ethos. Shridharani engrossed himself in the relief work in Punjab in the wake of communal violence amid Partition. He served as an officer on special duty in the Foreign Ministry under Jawaharlal Nehru. (Krishnalal Shridharani, Raman Soni (1998), Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, Page 11)

Active as he always was, Shridharani worked as Amrita Bazar Patrika’s Delhi correspondent and wrote for international publications such as The New York Times, Vogue, Saturday Review of Literature, and Tokyo Shimbun. (Shridharanini Shabdasrushti, Editor: Deepak Mehta, (2012), Gujarat Sahitya Sabha, Ahmedabad, Page 176).

He met Sundari, a Shantiniketan alumnus and a dancer with international exposure, and married her. The couple had two children, Amar and Kavita. But Shridharani departed too soon, in 1960, at the age of 49. He is considered a major poet-writer in Gujarati, but his contribution to America’s civil rights movement and other pursuits remain largely unexplored in his home state.

Urvish Kothari is a senior columnist and writer based in Ahmedabad. He tweets @urvish2020. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the Gujarat Giants series.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)