At 7:42 A.M. on February 27, 2002, Sabarmati Express pulled into the train station of Godhra, a small town in the Western Indian state of Gujarat, ruled by a Hindu nationalist government since 1995. What exactly happened at the train station and soon thereafter remains trapped in different narratives. Some details can, however, be reconstructed with sufficient assurance.

Sabarmati Express was carrying cadres (karsevaks) of the Hindu right from Ayodhya, where they had gone to express their vigorous support for building a Ram temple at a legally and politically disputed site. At Godhra, apparently, an altercation took place between Hindu activists and some Muslim boys serving tea at the train station. As the train began moving after its scheduled stop at the station, the emergency cord was pulled. As a result, the train stopped in a primarily Muslim neighborhood where, according to credible press reports, it was attacked by a Muslim mob. Two carriages were burned, and the firefighting efforts hampered. The fire killed 58 passengers, including many women and children.

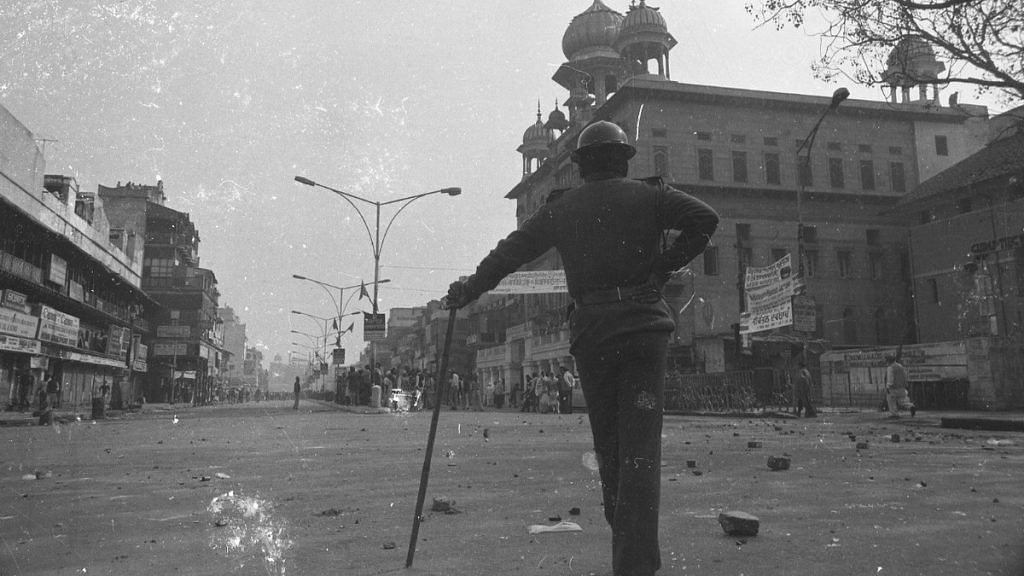

A retaliatory bloodbath followed in many parts of the state. Hindu mobs torched Muslim homes and businesses, killed Muslim men, women and children, and erased mosques and graves. Instead of isolating those Muslim criminals who attacked the train and punishing them legally, as any law-bound and civilized government would do, the state government allowed revenge killings. Over a thousand lives, possibly many more, were lost over the next few weeks. Over 100,000 Muslims were pushed into the state’s ramshackle refugee camps, where basic amenities were minimal and living conditions abysmal.

Hindu-Muslim riots are not uncommon in India, but Gujarat violence plumbed new depths of horror and brutality and has come to acquire a double meaning. It was a bruising embarrassment for anyone who believes in the pluralistic core of Indian nationhood, a view enshrined in India’s constitution, a view that gives an equal place to all religions in the country, privileging none.

Hindu nationalism, India’s Hindu right, reads Gujarat violence differently. It believes in an India dominated by its majority community, the Hindus. All other religions, it has always argued, must “assimilate” to India’s Hindu core, accepting in effect that the Hindus are the architect of the Indian nation and also its superior citizens. For Hindu nationalist ideologues, the anti-Muslim violence was an ideological victory. In a formal resolution, the RSS, the ideological and organizational centerpiece of Hindu nationalism, said: ‘‘Let the minorities understand that their real safety lies in the goodwill of the majority”. Laws alone, the RSS implied, as it always has, cannot protect India’s minorities.

Such views, of course, can be expressed in a democracy that protects free speech. The crux of the matter lies elsewhere. Press reports make it plausible to argue that the anti-Muslim retaliation was significantly abetted, if not demonstrably sponsored, by the elected Hindu nationalist government of the state.

Were Gujarat killings pogroms, not riots? Has independent India had any other pogroms before? And what are the implications of such violence for our understanding of the role of the state in ethnic or communal riots? These are the critical issues raised by Gujarat violence.

Also read: The Delhi pogrom 2020 is Amit Shah’s answer to an election defeat

Riots or Pogroms?

In one respect, the violence in Gujarat followed a highly predictable pattern. A recent time-series constructed on Hindu-Muslim violence had already identified Gujarat as the worst state, much worse than the states of North India often associated with awful Hindu-Muslim relations in popular perceptions. It had also specified three Gujarat towns — Ahmedabad, Vadodara and Godhra—as the most violence-prone: these three turned out to be the worst sites of violence in March and April 2002. It was also argued that the outbreaks of communal violence tend to be highly locally concentrated: many towns, only a few miles away from the worst cities, have insulated themselves from communal riots, entirely or substantially. In contrast to Ahmedabad, Surat’s old city (not the part where its shantytowns are) was argued to be such an example: yet again in March and April 2002, the violence in Surat was minimal, even as Vadodara and Ahmedabad, neither too far away from Surat, experienced carnage.

Not everything about Gujarat violence was, however, entirely predictable. In one respect, the violence was shockingly different. Unless later research disconfirms the proposition, the existing press reports give us every reason to conclude that the riots in Gujarat were the first full-blooded pogrom in independent India.

According to dictionaries, a pogrom means:

“An organized, often officially encouraged massacre or persecution of a minority group, especially one conducted against Jews.” (www.dictionary.com)

“A mob attack, either approved or condoned by authorities, against the persons and property of a religious, racial, or national minority.” (www.britannica.com)

Reports in almost all major newspapers of India, with the exception of the vernacular press in Gujarat, show that at least in March, if not April, the state not only made no attempt to stop the killings, but also condoned them. That the government “officially encouraged” anti – Muslim violence—something often believed—cannot be conclusively proved on the basis of the evidence provided by newspaper reports, though later research may well prove that. What is unquestionable is that the state condoned revenge killings.

The statements of non-governmental organizations most closely associated with the state government are highly indicative. According to the chief of one such organization, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), a leading Hindu nationalist body, Gujarat was “the first positive response of the Hindus to Muslim fundamentalism in 1,000 years”. The reference here is to the original historical arrival of Muslims from Central Asia and the Middle East to the Indian subcontinent, a time when a long Hindu decline, say the Hindu nationalists, also set in. On this reading, the rise of Muslims in Indian history and the Hindu decline are integrally connected, the former causing the latter, and a revenge for historical wrongs is necessary.

The Hindu right believes that its elected government did exactly what was required: namely, allowing violent Hindu retaliation against the Muslims, including those who had nothing to do with the mob that originally torched the train. For others, of course, it is not the job of the government, whatever its ideological persuasion, to stoke public anger, or to allow it to express itself violently, regardless of the provocation. No elected government that has taken an oath to protect the lives of its citizens can behave the way criminal gangs do, thirsting for a tit-for-tat. This is why Gujarat killings have been a source of bitter debate and intense agony in India.

It is sometimes suggested that the anti-Sikh violence in Delhi, after the assassination of Indira Gandhi on October 30, 1984, was the first pogrom of independent India. This argument is not plausible, for the differences are critical. To illustrate the major differences, one can do no better than cite from a most brilliant column written by a senior Indian journalist, who personally covered the 1984 anti-Sikh riots:

First of all, the ordinary mass of the Hindus in Delhi never got involved in the riots—many of us put on crash helmets, picked up hockey sticks and cricket bats, wickets, anything at night to run vigils in our streets so no “outsiders” could harm our Sikh neighbours. How many such stories have we heard from Gujarat? Second, once the government got its act together (within 72 hours) all rioting stopped, as if someone had blown the whistle and called off a game or a movie show. Third, and this is the most important distinction, there was shame, embarrassment, contrition, even fear on the faces of the top civil servants, police officers, Congressmen. They knew something terrible had happened. Rajiv Gandhi may have made his insensitive “when a tree falls earth shakes…” statement to rationalise the killings, but damage control started immediately.

….[A]s the riots were dying out on November 3 (Mrs. Gandhi had been assassinated on October 30) Delhi’s Lieutenant-Governor, P.G. Gavai, was fired.…The Station Head Officer (SHO) of Trilokpuri (police station) was removed on November 2. The police commissioner, Subhash Tandon, was replaced on November 12. So were Deputy Commissioner of Police (east), under whose jurisdiction Trilokpuri fell, Additional Police Commissioner (range), and Deputy Commissioner of Police (south). Within a month or so they were all facing departmental inquiries. Contrast this with what happened in Gujarat. Did any policeman get removed or punished for non-performance or complicity? Narendra Modi, on the other hand, moved out mainly those who had been effective, true and loyal to the uniform….

The Congressmen whose names surfaced or were even popularly mentioned in connection with the killings all paid the price. Political careers of H.K.L Bhagat, Jagdish Tytler and Sajjan Kumar never recovered from the taint of 1984 although nobody was ever convicted…. Isn’t it a bit different now when leading lights of the BJP go around talking of “Hindu consolidation,” of Modi having become a “Hindutva hero” or the likely electoral dividend of the killings?”

The larger point should be clear. Because of their intense anti-Muslim ideology and a Hindu conception of the nation, the leading Hindu nationalist organizations, such as the VHP and RSS, have celebrated the anti-Muslim violence as an act of nationalism. In contrast, the Congress party never developed an anti-Sikh ideology. This should explain why the Congress ended up developing an attitude of contrition, but the VHP, deeply intertwined with the state government in Gujarat, found hacking and burning Muslims after the Godhra provocation a celebratory and ideologically correct act. It is the latter which makes Gujarat riots a clear pogrom. There is no contrition yet in the statements of the Gujarat state government, or of leading Hindu nationalist organizations. The anti-Sikh violence of 1984 was significantly different.

In the Gujarat government’s eyes, Muslims are disloyal and deserve to be treated harshly, regardless of whether all Muslims were involved in, or supported, the torching of train at Godhra. No distinction need be made between Muslim criminals and innocent Muslim citizens. And the most powerful civil society organizations—the VHP and RSS— are also of the same view. Instead of civil society resisting the state, or the state resisting marauding civic groups like the VHP, there was a coincidence between the two in March 2002. It is this coincidence that created the ideal conditions for a pogrom.

Also read: One thing was distinctly rotten about 2002 Gujarat riots: use of rape as a form of terror

In later essays, I used the term “semi-pogrom” for Delhi 1984, while noting that Gujarat 2002 was a “purer form of pogrom”. In Delhi 1984, (a) the state looked on while mobs killed Sikhs, but (b) there was no ideological element in it (Congress did not have an anti-Sikh ideology). In Gujarat 2002, both (a) and (b) were present. The ideology, of course, was anti-Muslim.

This article first appeared in the Social Science Research Council, New York’s journal, Items and Issues, in Winter 2002-3. It has been republished with permission from the author.