On Sunday night, the waves of the Arabian sea lapping the shores of Pakistan’s largest city, Karachi, had competition from miles and miles of human beings packed into the Bagh-i-Jinnah in the heart of the metropolis. This was the ‘jalsa’, or rally, organised by the Pakistan Democratic Movement, a conglomeration of opposition parties from all over the country.

For several hours, the Bagh echoed with slogans that had first rent the air last Friday in Gujranwala, just outside Lahore, in the heart of Pakistan’s Punjab.

Also read: Pakistani women have led democracy protests. Can Maryam Nawaz do it now?

Bilawal takes over

This Sunday night was special. It was also the 13th anniversary of the return of Benazir Bhutto to Pakistan from exile in Dubai and London in 2007. Her cavalcade had taken hours and hours to reach the city from the airport when two bombs exploded, the second by a suicide bomber, killing more than a hundred people. Benazir survived because she had just sat inside her van. Three months later, another assassin ensured he got his mark. Her son, Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari, was 19-years old.

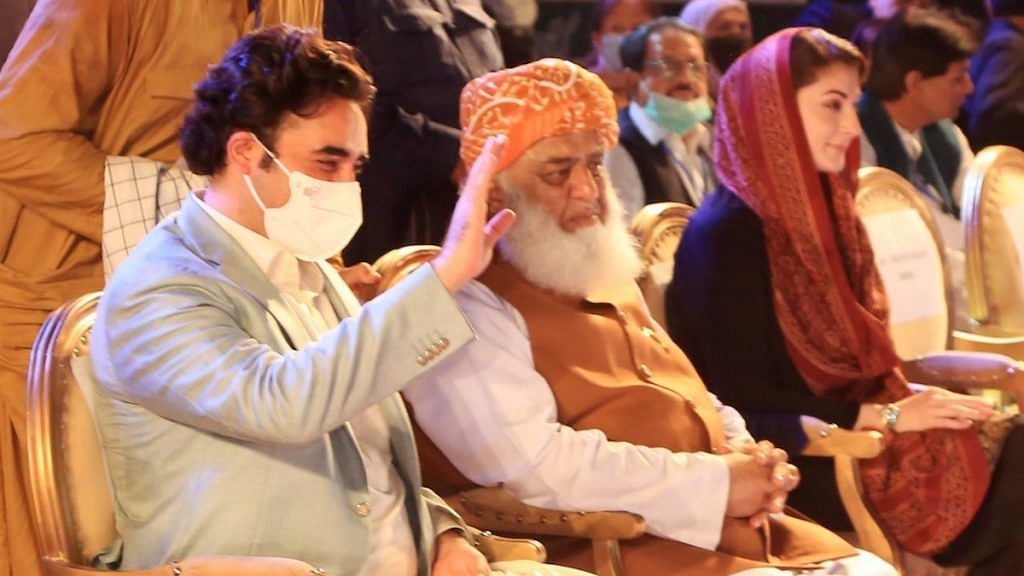

On Sunday night in Karachi, the 32-year-old president of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) ran his hand repeatedly through his hair and beseeched the crowd to deliver on the side of democracy. It was a magnificent performance by a passionate young man, so keenly aware of the tragic legacy of his family, which he knows he must transmute into something real if he has to write his own history into Pakistan’s pages.

Perhaps, the comparison with South Asia’s other dynasty scion is overdone and, therefore, odious – but necessary. Like Rahul Gandhi, Bilawal lived and studied abroad, except Rahul was never in exile. Unlike Rahul, Bilawal seems to have made a huge effort to overcome his deracination – although the word “fascism”, in Oxford-accented English, slipped into his speech a couple of times. Where Rahul Gandhi is sullen, Bilawal Bhutto seems personable. The idea of inheriting a political party probably appeals to both, but Bilawal seems to be far more willing to put himself out; for the not-so-young Gandhi, politics is more noblesse oblige, less hard work.

Also read: Why Gandhis losing to Modi has a clear lesson for PPP’s Bilawal Bhutto

All on the stage

And yet the Sunday rally belonged to three Pakistani politicians for whom the state, as well as the media, usually have little time for – Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM)’s Mohsin Dawar, Pakhtunkhwa Milli Awami Party’s Mahmood Khan Achakzai and Balochistan National Party’s Sardar Akhtar Jan Mengal.

For each of them, consigned to the margins by the Pakistan military and political establishment, it was an opportunity to come centre-stage and talk about their ideas of Pakistan. Dawar has pointed to how PTM protesters are routinely stopped by the military from participating in rallies and sit-ins or just meeting fellow Pashtuns; Mengal spoke about missing persons back home, how gas and electricity had become so expensive and lives so cheap; while Achakzai said Pakhtuns were accused of treason when they talked of federalism.

Two phrases, “selected Prime Minister” and “hybrid governance” resonated through the evening; they had, of course, been sparked off by former PM Nawaz Sharif’s hour-long speech over video from London at the Gujranwala rally. “Who pushed for a ‘selected’ government in Pakistan…Kisne nalayak Imran Niazi ko Wazir-i-Azam banaya?” asked Nawaz Sharif, leaving no one in any doubt that he was accusing the all-powerful Pakistani army of dislodging him from the PM’s chair and putting Imran Khan in it through a motivated chain of events.

Also read: Why is the army in Pakistan dangerous for democracy? Answer goes back to 1947

J’accuse moment

So what now? Three more years are left for the general elections in Pakistan, and even if the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) intends to expand its presence by holding rallies in Quetta, Peshawar, Multan and Lahore over the next couple of months, there is little the opposition can do to overthrow Imran Khan. Moreover, the army is probably being patient. It is certainly not about to roll over and cede power just because a few lakh people jam the roads and stay up all night listening to speeches by charismatic civilians.

And yet, there’s something electric in the air in Pakistan these days. The open challenge to the Pakistan army has happened before – Pervez Musharraf most lately, in 2007, although he was president by then. This time around, though, the accusations are against senior figures in the military establishment who wield real power and do not brook any challenge to their authority.

People like army chief Gen. Qamar Javed Bajwa and ISI chief Gen. Faiz Hameed. There has always been a plethora of euphemisms for people like them – the khakhis, the angels, the “khalai makhlooq” or alien creatures. For the first time, Pakistani politicians are naming these men and pointing fingers at them publicly.

J’accuse, says Nawaz Sharif. I accuse you. You are guilty.

Also read: Pakistan PM Imran Khan slams Nawaz Sharif for accusing army chief of rigging elections

A churning

So, have the people’s politicians bitten off more than they can chew? The example of Benazir Bhutto is in front of Pakistan – she dared them to shut her up. They did.

There’s another difference this time around, which is that these rallies are taking place at a time Pakistan seems to be on the verge of financial collapse. Food prices are soaring and Pakistan is importing the most tomatoes, wheat and sugar in a decade. Of course, military expenditure is rising.

Adding to the budget’s $20.7 billion fiscal gap is another $22 billion borrowed from the international community — $5.5 billion from Saudi Arabia, UAE & Qatar, $6.7 billion from China and $4.8 billion from the IMF and ADB.

Still, something is happening in Pakistan. It’s not clear yet whether the people are rising – they’re turning, for sure. For us in India, the people next door, perhaps the PDM is likely the most important shift in Pakistan’s contemporary history.

Views are personal.