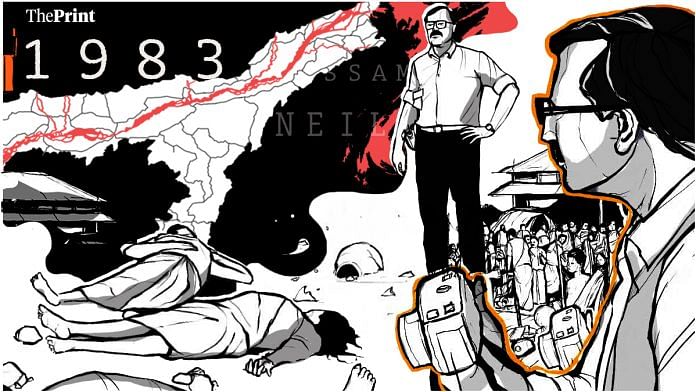

Why are we writing about what happened in Assam decades ago, now? And why are we committing to doing not just one article, but a series of two, on successive Saturdays, our customary National Interest slot?

First Person/Second Draft is an occasional series I started in mid-2013 inspired by Shoojit Sarkar’s brilliant film Madras Cafe, set in the terror phase in Sri Lanka leading up to Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination. On India’s Independence Day that year, I was invited to deliver the annual Sri Lanka India Society lecture.

Fresh from watching the film, it gave me an opportunity to revisit many of the moments, places and people that featured in my decade of covering the Sri Lankan crisis, 1984-94. The result was a series of articles.

After that, there were more in the series, including articles on Punjab. You can find these here. In the course of time, these might feature as much more detailed accounts in a book. Until then, I will keep bringing you occasional series like these, especially when something brings back any of the big stories I covered in my decades as a field reporter. These were stories I covered and witnessed in the first person. Changes in the course of time, and the benefit of hindsight, now give us an opportunity to write a second draft. That’s why the series First Person/Second Draft.

The idea of this Assam series was sparked about two weeks back, at a small and solemn gathering of a group of friends and acquaintances at New Delhi’s Lodhi Estate electric crematorium. We were there to mourn Vinay Kohli, a distinguished 1966-batch IAS officer of the Assam-Meghalaya cadre. Several key fellow travellers and admirers were there. I met some after years, and a few after decades.

There was Madan P. Bezbaruah of the 1964 batch, who was Assam’s Home Secretary in my years there, in the late 1980s. There were also ‘young’ Jitesh Khosla and Anup Thakur (both of the 1979 batch) with their wives. Like Bezbaruah, both these Assam cadre officers retired at the rank of central government secretary. But I say ‘young’ because that’s what they — and I — were during that troubled epoch in the northeast. I met them both on their first (or thereabouts) posting in service, as sub-divisional Officers in Golaghat and Mangaldai respectively.

I was of course there looking for trouble to report. And during that awful fortnight, when Indira Gandhi decided to force an election nobody wanted in Assam, you didn’t have to go looking for trouble. It followed you all the time, whether you were an officer or a reporter. Many vivid memories had returned that morning at the funeral.

Then, serendipitously, my colleague Praveen Swami, the National Security Editor at ThePrint, reminded me that this first fortnight of February was going to mark that bloodiest one in Assam, where by my reckoning about 7,000 people were killed. Even the official estimate was nearly half of this.

That’s why this first article in this series of two. This one is on how the violence built up during the election campaign. The next article, on Saturday, 18 February, will mark the exact date of the 40th anniversary of the Nellie massacre. I just recorded a video and a podcast with my eyewitness account of that massacre, and you can watch/hear it here.

The next article will talk about how some of us, working with Arun Shourie then, unravelled an incredible story of incompetence, negligence, cover-ups and even complicity that resulted in those great killings over a fortnight. Some of these accounts draw from my 1983-84 book Assam: A Valley Divided, long out of print.

Also Read: In Kashmir 3 years on, 3 positive changes, 3 things that should’ve happened & 3 that got worse

‘You will be counting corpses in hundreds’

Looking back, with the benefit of hindsight as I just said, what stands out is how complacent, distracted, harassed, complicit and insensitive the police were then. Which takes me straight back to earlier rounds of violence in Nowgong (now Nagaon) district, where Nellie was also located. A junior officer was candid about the situation a week before Nellie: “I wish the bubble in Nowgong had burst earlier, like in Darrang. Now if it does so during the elections, you will be counting corpses in hundreds.” How prophetic his words proved to be.

The first symptoms appeared the day after this conversation. In the heat and dust generated by the riots at Chamaria, west of Gauhati, most people ignored the happenings around Jagiroad in Nowgong district, a mere 15 km from Nellie. Five persons were killed in what looked, prima facie, like a communal clash. But no one seemed to be in a hurry to find out who had killed whom, as so many were getting killed all over, anyway. This was, in fact, the first sign of the build-up of tribal frenzy that would hit the Nowgong plains like a devastating tornado five days later.

The frequency of the ‘near things’ increased and, on the eve of polling, tension had built up to such a degree that a large-scale outbreak of violence seemed inevitable in the bulk of the district. Nowgong is the land of the most ‘Assamised’ tribals in the state. After their victories against the Kacharis, the Ahoms had allowed certain offshoots of the tribe to inhabit Nowgong. The Lalungs, who had been vassals to both the Kacharis and the Ahoms, were the main beneficiaries.

They inhabited this most fertile section of the Brahmaputra valley freely, till the immigrant Bengali Muslims came on the scene at the turn of the 20th century. In the great immigrant scramble for land, the Lalungs were the worst sufferers. The tribe (population about 3.71 lakh according to the 2011 census) lost most of its good land and was pushed deeper towards the various tributaries of the Brahmaputra, particularly the Kopili, and into the jungles along the Mikir hills.

Later, the British administrators clumsily tried to prevent alienation of tribal land through a “line system” under which imaginary lines were drawn across various parts of the infiltration-prone districts. The Bengali settler was forbidden from crossing the “line” but always succeeded in exploiting the gullibility of the backward tribal living across it. The line was pushed deeper. Even a cursory analysis of the violence in Nowgong showed that this, even now, remained the line that divided the two warring groups. The systematic tribal attacks came across the pre-Independence “lines”.

The first signs of serious trouble appeared all along the bank of the river Kopilli, which also, incidentally, flanks the Nellie salient. The tribals launched a series of relatively ineffective attacks and the Muslims retaliated with an attack on the village of Bakulguri on 16 February. The tribal reprisals on Padumani, resulting in four deaths, quickened the pace of the developments and tension mounted high in and around Hojai, the town famous for its agarwood traders (agarwood, a fragrant forest produce, is smuggled in from Burma and used for incense). That’s the town, incidentally, where Badruddin Ajmal, the Asaduddin Owaisi of Assam, comes from. He’s a fragrance trader too.

This later made an indirect contribution to the carnage in Nellie in that the administration’s attention was concentrated on Hojai, which was regarded as a sensitive pocket. The town was placed under curfew and since, for the moment, the police seemed to ignore the western parts of the district, things happened with bewildering rapidity.

The ‘durbar’ that decided to kill

Now, the immigrant Muslims kidnapped five of a family of Lalungs. Their bodies were found the following day, and word quickly spread that the two young girls among them had been gang-raped. Even as tribal reprisals around the nearby village of Nagabandha left over 20 immigrant Muslims dead, the Lalung rajas (chiefs) from the major habitations of the tribe went into a huddle in a tea garden. They decided to launch an all-out attack on the immigrant areas.

There are different versions as to what exactly transpired at the ‘durbar’. According to an account given to me by some educated Lalungs, the instigation had come from some local, small-time AASU-AAGSP leaders, who may have been connected with the RSS as alleged then but never established, given the hold of the organisation over the nearby Kampur area to the south. The Lalung chiefs are said to have decided that they must kill at least 700 for each of their tribesmen killed.

Before Nellie, the only act of defiance the Lalungs, a Hindu Shaivite tribe, were credited with was the killing, in 1861, of a British officer who tried to prevent them from cultivating opium, which was then the mainstay of their economy.

It is possible that certain elements successfully exploited Lalung ire, but basically the outburst originated from suspicion and hatred which had built up over the years, against people who had usurped their land. It was a curious bunch that began getting together in tea gardens and forests around Nellie. The Lalungs had roped in some Karbis, and there was a generous sprinkling of non-tribal Assamese Hindus, and even some Nepalis.

The rest is relatively better known history; the wireless message from Zahiruddin (the officer commanding of the Nowgong police station) containing a forewarning of Nellie, which was ignored, is part of it. We will talk about the message — and how I found it in the flickering light of a hand-held electric bulb late one evening in Nowgong police station — in next week’s instalment next week.

It can, however, be said in defence of the police that even as Nellie was attacked, they were more than fully stretched with similar situations arising in dozens of places in the district. The most dangerous was Radhahati, called the Chambal of Assam, the land ruled by dacoits who operate from islands in the Brahmaputra.

On the morning of 17 February officials at Nowgong received alarming reports that a large force of immigrant Muslims, led by the bandits, was about to launch a frontal assault on the town of Dhing, predominantly inhabited by the Assamese. It was not a false alarm either, as a CRPF post on the outskirts of the town radioed a message to the district headquarters saying that they were being fired upon with automatic weapons. This particular CRPF unit had recently been withdrawn from the counter-insurgency theatre in the north-eastern hills and carried self-loading rifles. The CRPF men opened fire and this must have been the first time in the country’s independent history that a police force freely fired automatic rifles and a light machine gun in a law and order situation.

Over 200 rounds were fired and even though they killed only six of the attackers, the fusillade must have dampened the enthusiasm of the rest. Later, as Nellie consigned all other incidents to relative insignificance, the third phase of the violence began with the immigrant Muslim people looking for revenge, burning villages around Samaguri, between the nights of 21 and 23 February. But the police were always close on their heels and managed to avert massacres in the nick of time. The fortnight of chasing shadows in the wild had by now left the police force too exhausted to be effective.

Also Read: Mandir or Masjid? New surveys not needed, just acceptance of truth & move towards reconciliation

Fresh rounds of violence

The Muslims’ retaliatory move was a disaster. In fact, in fresh rounds of violence a week later around the Amtala forest, another 60-70 of them were killed and quietly buried in the marshes. Zahiruddin discovered the skeletons three weeks later.

Around Amtala, however, the immigrants had also faced a slightly different enemy — the Assamese Sikh. A number of villages around Nowgong are inhabited by Assamese who had converted to Sikhism centuries ago.

Armed Assamese Sikhs passed off easily as CRPF and BSF men in mufti, and by the time the luckless immigrant villagers saw through the ruse, it was too late. In fact, one of the first persons to die in police firings in Nowgong district during the election campaign was Chandan Singh, an Assamese Sikh who, police insisted, was a confirmed extremist.

Police attention also shifted away across the river, to the north bank of the Brahmaputra, with killings and riots breaking out in the most poorly-connected and forested regions. It was impossible to sift fact from fiction. Sometimes a dozen dead were 1,290 in reality, and sometimes 120 reported initially weren’t even four. It was that kind of fortnight. Gohpur, Chaulkhowa Chapori (river island) and all of these took our attention away from Khoirabari, deep east on the north bank, where the second-biggest massacre took place besides and before Nellie.

Thus, when the mobs gathered into a frenzied army of 10,000 at a high school in Khoirabari, the town had no more than five policemen led by a weak assistant sub-inspector hailing from Cachar. Following a well-laid-out plan, the mobs went out to encircle and annihilate Bengali villages, while the policemen decided that discretion was the better part of valour.

Simultaneously, Assamese mobs struck the Bengali Hindu area of Goreswar in the west, cutting off all escape routes. The government formally announced about a hundred dead, and informally accepted a figure of around 600. But if one is to go by the version of the BSF jawans who came in after the killings, the toll was not less than 1,000.

“There were heaps and heaps of bodies just like Bangladesh”, recalled a veteran, adding, “I counted 97 on the outskirts of one village.” Two weeks after the killings, I saw vultures still scraping dozens of skeletons lying in the fields.

On 3 March when we reached the place, the wounded survivors were still hiding out of fear and it was difficult persuading them to come out, even after the police arrived. The totally disorganised state of the administration during those days is reflected in the way the Chaulkhowa signals were ignored. The officer commanding of the Sipajhar police station had had reports of the build-up for the attack but was too busy trying to guard the bridges on and around the national highway and the government installations to do anything about it.

‘Mobs kept coming even when you fired straight on’

Five days after the first attacks, some survivors managed to get out of the char (river islands, floodplains) lands, taking the tale of the killings to people in the immigrant-majority villages of Dhula and Thekerabari, east of Mangaldai. This led to immigrant Muslim attacks on the Assamese villagers that took a toll of about 70. In retrospect, thus, the sequence of events was the killing of immigrant Muslims at Chaulkhowa, reprisals against the Assamese at Dhula, etcetera, and then the great killings of Nellie right across the river from Mangaldai.

If Darrang and Nowgong cornered attention, the other districts, too, were not free of violence. Goalpara had had about 300-400 dead in a series of ethnic clashes, and the obscure district of North Lakhimpur, where nobody ever seems to know what is happening, had logged a toll of over 1,000, as Assamese Hindu and Mising tribal hordes attacked village after village of Bengali Hindus and Muslims, deep in the east almost bordering the Sadiya frontier tract. The survivors took to the river and escaped to distant islands, but were again attacked.

Nothing better characterised the atmosphere in those frenetic February days. Everyone feared everyone; fear and hatred made a dangerous mix and took a toll of 7,000. It is difficult to club the clashes under any one general term as communal, ethnic or linguistic. They were probably a combination of all factors.

The violence was still continuing when K.P.S. Gill and the commissioner of the Upper Assam Division, V.S. Jafa, arrived at Mangaldai by helicopter. The sub-divisional police officer, S. Ahmed, who went up to the helipad, was in tears. “You know, sir, how brutally they killed Handique,” he said and broke down. The mutilated, disfigured, crushed and burnt body of circle inspector Ghana Kanta Handique lay outside the compound of the Mangaldai hospital as if on public display.

A CRPF commandant was the most accurate with his assessment. He said, while helping us negotiate a partly-burnt bridge, “For 25 years I have made a living out of controlling violent mobs. But this lot was different. For the first time, I saw mobs that kept coming even when you fired straight on. We decided to withdraw because continuing firing would have resulted in a Jallianwala Bagh.”

Also Read: Nagaland massacre shows AFSPA is a deadly addiction. Does Modi govt have the courage to kick it?