The months-long farm protests have brought into focus the role of the Food Corporation of India and its procurement of food grains from farmers in Punjab and Haryana. The Food Corporation of India (FCI)’s two vital objectives are to purchase food grains for distribution through the public distribution system (PDS), and to maintain enough stocks for ensuring national food security. On these two, it has delivered well, as evidenced during the pandemic.

However, FCI’s third objective — providing price support to farmers — is tangential to the other two. To achieve this objective, FCI procures hundreds of lakh metric tons of wheat and rice each year in what is one of the biggest farmer welfare programmes in India. A farmer welfare programme should be benefitting those most deserving of support – poor farmers. However, FCI’s procurement does not serve them.

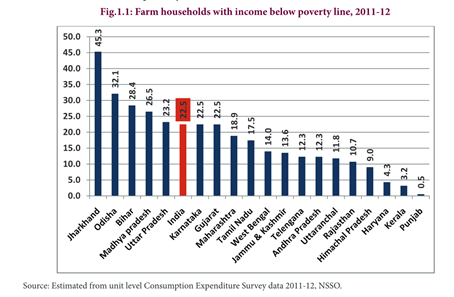

Undisputedly, many farmers do require income support. In 2012-13, government bodies estimated that the average farming household earns Rs 77,112 annually, with almost 50 per cent coming from the cultivation of crops. However, not all farmers are equal. Small and marginal farmers have tiny landholdings, which places a tremendous constraint on their gross incomes. About 53 per cent of farm households operated on less than 0.63 hectares of land, and their agriculture income was simply insufficient resulting in around 22 per cent of farm households nationally being below the poverty line.

Also read: Everyone agrees farm reforms are needed. Here’s how Modi govt can break political deadlock

How to benefit below-poverty-line (BPL) farmers

To achieve farmer welfare, FCI’s procurement should be benefitting these below-poverty-line (BPL) farmers and, therefore, the procurement patterns should mirror the BPL patterns. Unfortunately, FCI’s procurement today is mostly done from medium and large-scale farmers. Almost 86 per cent of Indian farmers are classified as small and marginal, most of whom simply do not have a marketable surplus beyond home consumption, and therefore, are in no position to take advantage of FCI’s procurement support. Those who do have a surplus, face a lack of capital, are unable to travel to FCI procurement centres, and are forced to sell off their produce at the village level.

Additionally, FCI’s procurement is not oriented towards serving geographies with the greatest number of poor farmers. Punjab had less than 1 per cent of farm households below the poverty line, whereas Jharkhand had 45 per cent (see Figure 1.1). But FCI’s procurement is skewed towards states like Haryana and Punjab, where poverty amongst farm households is almost absent.

Thus, as a farmer welfare programme, FCI’s procurement is not reaching the right beneficiaries. It is ineffective for farmer welfare, since it doesn’t benefit the most deserving. Additionally, there are well-documented inefficiencies in FCI’s functioning – inadequate warehousing facilities, rotting grains, grains being sold in the open markets at a loss, manual labour being paid exorbitant monthly wages, etc. The FCI’s economic cost of food-grains for rice and wheat is about 40 per cent – 50 per cent higher than the procurement price paid to farmers.

Also read: Pakistanis should worry why their farmers are not protesting like those in India

Conflicting roles of FCI

One of the central reasons behind these issues are the conflicting objectives of the FCI. Its two strategic objectives — providing food-grains through the public distribution system (PDS) and buffer stocks for national food security – need efficient, scalable, and stable operations, which means procurement at a low operational cost, from locations with good procurement infrastructure, the opportunity to increase supplies at short notice, and good logistical support. The FCI is well equipped to do this, with its current practices of concentrated buying from a few states, mainly from medium and large farmers.

Farmer welfare requires reaching out to small and marginal farmers, which necessarily creates diseconomies of scale. Additionally, a procurement programme is ineffective for this set, since they lack a surplus to sell. Instead, small and marginal farmers require a combination of income support through direct bank transfers, investments in agri-R&D, technology deployment and setting up of Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) to increase their yields and help get proper price realisations. Thus, farmer welfare requires a vastly different set of activities than the FCI’s current procurement capabilities.

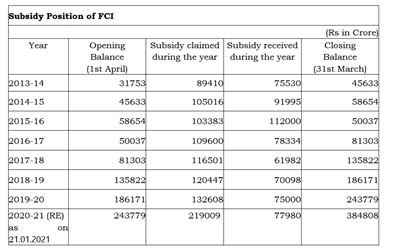

This conflict of objectives has rendered FCI’s farmer welfare programme inefficient and ineffective. To resolve this conflict at the heart of FCI, it is necessary to separate the welfare responsibilities from the strategic objectives. The procurement for PDS and national food security can still be handled by FCI, since that is what it is geared up to do today. Whereas farmer welfare needs to be handed over to another organisation that is designed towards serving BPL farmers. It is especially important to rectify this, considering that the FCI’s borrowings has led to the Union government spending an estimated Rs 4.2 lakh crore on food subsidy in 2020-21, while agri-R&D got a meagre Rs 0.07 lakh crore. Another Rs 2.43 lakh crore are budgeted towards the food subsidy bill in FY 21-22.

The large-scale nature of this expense at a time of rising government fiscal deficits makes it imperative to utilise these funds effectively, and reorganising the FCI will go a long way towards serving our national interest.

Omkar Sathe is an IIM Calcutta alumnus, with a keen interest in public policy. Sahil Deo is a co-founder of CPC Analytics, a data-driven policy consulting firm with offices in Pune and Berlin. Indraneel Chitale is the Managing Partner at Chitale Group, Co-Founder at Herbea and an active investor. Views are personal.

Nice article. It’s sad that instead of benefitting the small farmers, the lakhs of crores of rupees spent every year by FCI benefits big farmers who don’t need Govt support. It’s the tragedy of democracy where the big farmer is politically influential while the small farmer is politically invisible.

I know from personal experience that small farmers don’t benefit from MSP procurement, but benefit from Kisan Samman Nidhi. But due to the political power of big farmers who dominate farmer unions, Govt keeps increasing budget for MSP exponentially every year while ignoring Kisan Samman Nidhi.

Its simple, effective, Wish this will fall into hands of PM. This solves inefficiencies of FCI and improve farmer, both in one shot. In the process will save tons of money which can fill the govt coffers which is depending mostly on Petrol cell for emergency needs. This can be another success story of current dispensation.

This is the first analysis based article aimed at solution. Unlike the typical argument FARMERS KNOW BEST which is like saying the patient knows best so we do not need the DOCTOR.

Majority of Farmers are in need of reforms which can only come from people of knowledge and not a bunch of LAHTIYAs and DALALAs who are the cause.