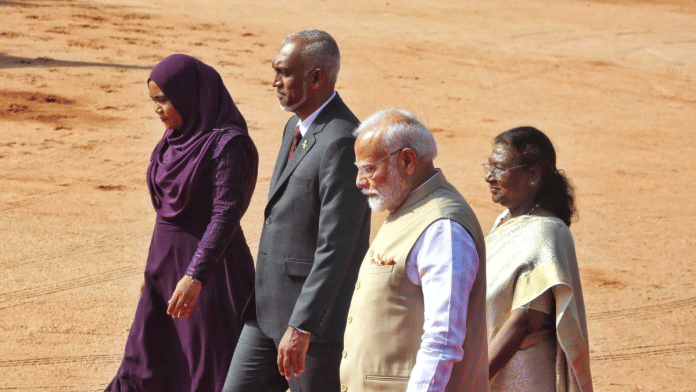

Mohamed Muizzu, the perceived pro-China President of the Maldives known for his ‘India Out’ campaign, is on a state visit to India till 10 October 2024. While some Indian media outlets see this visit as a significant U-turn, China views it differently.

Chinese analysts interpret Muizzu’s outreach to India as a necessity, driven by the Maldives’ declining foreign exchange reserves and a recent credit rating downgrade by Moody’s. They suggest that the visit underscores the Maldives’ need to diversify its economic options, including those offered by India. With the country’s public debt standing at around $8 billion—$1.4 billion of which is owed to both China and India—Muizzu cannot afford to alienate either. From China’s perspective, this visit is less a diplomatic pivot and more an economic imperative. On Chinese microblogging website Weibo, Muizzu’s trip to India has been largely portrayed as a pragmatic, though challenging, move.

This underscores an important realisation: While the broader Indo-Pacific and Indian Ocean regions are vital, China’s growing footprint in South Asia poses an immediate challenge to India. For China, South Asia is not just a strategic region for expanding influence but also a theatre for counterbalancing India’s dominance and keeping it contained within the region.

Also read: Chinese are seeing India as going soft. Talk of ‘consensus’ over disengagement rings hollow

The complex choice between India and China

India’s significance in China’s strategic calculus has noticeably increased, with more frequent discussions about its influence in South Asia and competition with its adversarial neighbour. Beijing actively promotes South Asian cooperation that deliberately excludes India. For example, last month, China hosted the seventh Dunhuang Cultural Expo and the Belt and Road China and Central Asia South Asia Cooperation and Development Forum. Given India’s opposition to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), its absence was striking, making the event appear intentionally exclusionary.

Additionally, China organised the fifth China-South Asia Cooperation Forum, further advancing its strategic outreach and reinforcing a “China-South Asia minus India” framework.

China has capitalised on discontent among some South Asian leaders toward India. From the Maldives to Sri Lanka, Chinese media often portrays India as a regional hegemon that is uneasy about China’s growing influence. A commentator on Baidu remarked, “India seems dissatisfied with the growing friendly relationship between China and South Asian countries. To push China out, India has increased its investments in smaller South Asian countries and wants to sow discord between China and its neighbours.”

Much of the discourse reinforces the notion that India’s traditional dominance in the region is waning. This perspective is amplified by academics like Long Xingchun from the School of International Studies, Sichuan International Studies University, who stated, “Attempts to hinder South Asian countries from collaborating with others through smear tactics are unhealthy, impractical, and unlikely to succeed.”

Chinese discourse suggests that amid the Maldives’ debt crisis, India may attempt to reassert its control, but China does provide an alternative. Analysts argue that China’s cooperation agreement with the Maldives came at a crucial moment—not only offering financial aid but also bolstering Malé’s capacity to push back against Indian influence. Similarly, following the recent Sri Lankan presidential election of Anura Kumara Dissanayake, discussions in China have intensified regarding India’s unease. Given Dissanayake’s history of ‘anti-India’ sentiments, Chinese commentators speculate on how his administration might challenge India’s standing in Sri Lanka.

There is a perception among Chinese analysts that India is responding to China’s growing clout and engagement in the region by ramping up investments in infrastructure and economic assistance, especially in Sri Lanka, where China’s investment in the port city of Colombo has bolstered its influence. Indian efforts, like providing economic assistance and collaborating on infrastructure projects, are seen as attempts to counterbalance the BRI. China views these moves as reactionary. A commentator noted, “The only major power in South Asia is India. India has influence in this region, mainly because there are no countries or forces that can check and balance it.” According to this view, India’s desire to maintain its dominant position is now being challenged by China’s growing economic presence.

India’s engagement in South Asia is not binary

For South Asian countries, the choice between India and China is far from binary. While China offers financial incentives primarily aimed at countering India’s influence, the burdens of heavy debt and long-term dependence on Beijing weigh heavily on these countries. Consequently, South Asian countries must navigate a complex balancing act—leveraging China’s economic opportunities while maintaining their ties with India, a neighbour with deep traditional, cultural and economic connections. For many, leaning solely toward China and using its influence against India comes with costs that are too steep to bear.

Despite China’s overtures, India remains an indispensable partner in the region. Moreover, China must recognise that relations with India are too significant for its South Asian neighbours to abandon, even if they do not fully align with New Delhi entirely. This reality was accentuated by Muizzu’s visit to India and the positive developments in India-Maldives relations.

Sana Hashmi is a fellow at Taiwan-Asia Exchange Foundation. She tweets @sanahashmi1. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

The converse is equally true. More for economics than geopolitics, barring Pakistan. South Asian countries would like more trade with and investment from China. Long term harmony and development in the region requires India and China making space for each other.