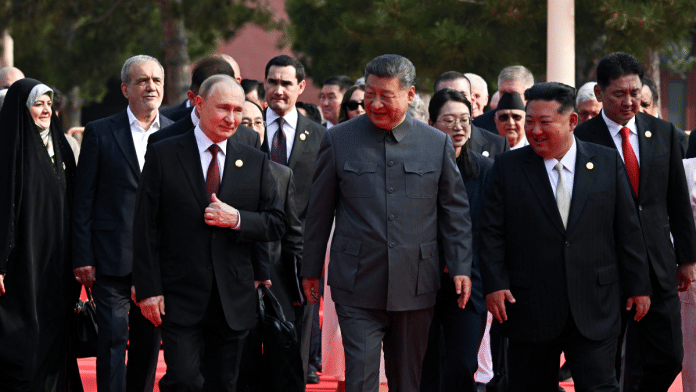

The idea of a new world order has long captivated scholars and policymakers around the globe, with China increasingly emerging as a focal point. Recent developments—the unveiling of the Global Governance Initiative at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit in Tianjin and the 93rd military parade in Beijing, attended by over 25 world leaders—have intensified speculation about Beijing’s global ambitions. The GGI purports to “promote the construction of a more just and reasonable global governance system” and foster a “community with a shared future for mankind”. International observers interpret such initiatives as indicative of China’s desire to reshape the global order according to its own vision.

Yet, a closer examination of Chinese-language sources complicates this narrative. Far from seeking to dismantle the existing international order, Beijing’s discourse emphasises defending, recalibrating, and guiding the current system, with China strategically positioned at its centre.

This raises a crucial question: Is China genuinely pursuing a new world order, or is it just advancing an agenda that asserts its centrality?

Defence, not revisionism

Chinese strategic discourse stresses that Beijing is not revisionist and harbours no intention of establishing a wholly new global order. A publication from Renmin University’s School of International Studies explains that China’s interpretation of the world order focuses on understanding the deep structure of international politics through historical, ideological, and systemic analysis. It does not view global relations solely through the lens of economics and military power. Rather than attempting to overthrow the current system, Chinese commentary positions the country as both defending existing frameworks and guiding their evolution.

Analysts in China argue that the country’s culture, philosophy, and worldview can play a constructive role in fostering cooperation and integrating with established international norms to create a more harmonious global order. They highlight that multiple visions of global governance coexist, from Europe’s emphasis on equality and democracy to Russia’s expansionist ambitions. According to them, however, the Chinese model is distinguished by pragmatism, centring China while promoting cooperation and mutually beneficial outcomes. Many commentators suggest that China’s rise provides the leadership necessary to maintain stability and advance a more peaceful, prosperous international system.

Three interrelated themes underpin this perspective:

- Historical rectification: China emphasises past injustices and the longstanding dominance of Western powers, framing its rise and leadership as a correction of historical imbalance.

- Capabilities as stabilisers: Beijing highlights its military, economic, and technological capacities as the foundation of its stabilising influence in global affairs.

- Multipolar leadership: China positions itself not as a unilateral hegemon but as a central actor within an increasingly interconnected international system.

Chinese commentators reinforce the historical injustice and rectification narrative. Gao Qiao, writing in People’s Daily, describes China as “an unwavering defender of the international order”, contributing “Chinese wisdom” and “Chinese solutions” to preserve the post-World War 2 order while improving global governance mechanisms. Shen Yi, professor of international politics at Fudan University, argues that the 93rd military parade demonstrated China’s strength, consolidated domestic and international support, and provided “a new source of power to guide the world forward during this turbulent crossroads”.

Multiple voices on the Chinese internet also reinforce the argument that China’s growing and unmatchable economic, military, and technological capabilities position it as an influential actor in shaping global governance. Fan Yongpeng, vice president of the Institute of Chinese Studies at Fudan University, describes China as the “ballast stone” of world peace, whose economic, technological, and military capacities provide stability in an unpredictable international system. A commentator on Baijiahao notes that China’s influence derives not only from military might but also from technological advancement, scientific investment, and integration into global markets, positioning it alongside the United States as a decisive actor in 21st-century international relations.

Chinese discourse stresses support for a multipolar world where other powers also play meaningful roles. European, Japanese, and Indian influence remains important, even as Western states face turbulence, protectionism, and declining sway. Meanwhile, developing countries assert greater autonomy and drive global growth, while China and other Eastern powers emphasise cooperation, resilient supply chains, and industrial integration. By prioritising partnerships over resource extraction, Beijing poses a challenge to the West-led order.

Scholars also note the shift in global power over the eight decades since World War 2. Qi Huaigao, vice dean of the Institute of International Studies at Fudan University, observes that China and the “Global South” are rising, enabling developing countries to shape international norms more effectively. Shen Yi adds that initiatives like the GGI provide guiding principles for global governance, reinforcing China’s stabilising role.

Also read: Revival of India-China trade through Lipulekh brings hopes, concerns for border traders

China at the centre

Chinese discourse consistently situates the country as a pivotal global actor. Hu Dekun, professor at Wuhan University, describes China as offering “a new model for the world” at a historical crossroads, with several analysts hinting at the decline of US-led unipolarity and the rise of a more East-centred order framed through the “Chinese dream”.

Amid Western political turbulence, Beijing projects itself as a responsible power, stabiliser, and innovator in global governance. Its emphasis is less on replacing the existing order than on reinforcing and reinterpreting it with “Chinese characteristics”. By combining historical correction, comprehensive capabilities, and leadership within a multipolar system, China positions itself as the anchor of a more balanced and interconnected international order.

Examples of such efforts include the Belt and Road Initiative, BRICS, the SCO, and the promotion of Chinese-style modernisation under the idea of a “community with a shared future for mankind”. The establishment of the International Mediation Court in Hong Kong in May this year, framed as moving beyond zero-sum thinking, illustrates how China blends Eastern traditions with modern rule of law to offer alternative models of dispute resolution. Commentators present these initiatives as evidence of constructive leadership, contrasting them with Western practices. Zhang Zhikun, senior researcher from the Kunlun Policy Research Institute, further links China’s rise to the revival of Eastern civilisations, positioning it as an alternative to Western dominance.

Chinese discourse suggests that Beijing’s rise is not an attempt to dismantle the global order but to place itself at the centre of a gradually evolving system. It intends to defend, energise, and reshape global governance while maintaining stability. Rather than heralding a radical break, Chinese discourse projects that the country advocates for a multipolar order in which its leadership and vision play a central role.

Sana Hashmi is a fellow at the Taiwan-Asia Exchange Foundation. She tweets @sanahashmi1. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)