Nykaa, the Indian beauty company started by a woman entrepreneur, Falguni Nayar, has recently been in the spotlight because of its stellar debut in the stock exchanges. As we celebrate its roaring success, let us evaluate the life trajectory of young Indian women, who are Nykaa’s prime customers.

We define young women as those who are in the age group of 20-29 years. The majority of women see significant life changes during these years – completing education, decision to take up paid work, marriage and moving into a new family and place, and starting a family. In 2018-19, there were around 92.4 million young women in India and around 10.7 per cent of them were in education, 9.5 per cent in paid work in industry and services (formal and informal sectors), and over 66 per cent were involved in domestic responsibilities, our estimates based on Periodic Labour Survey data shows.

Similar to Nykaa’s Nayar, many other Indian women have entered the start-up world successfully, hold top corporate positions in banking, information technology and other sectors. India elected a woman prime minister 50 years ago, has had a woman president and several women as the chief ministers of states. The gender norms for common women in India around marriage and childcare, however, continue to be strong, influencing the behaviour of both men and women, the existing research shows.

Also read: Covid has devastated India’s self-employed women

Who works in India— married or single women?

How does the picture look like if we look at married-versus-single young women?

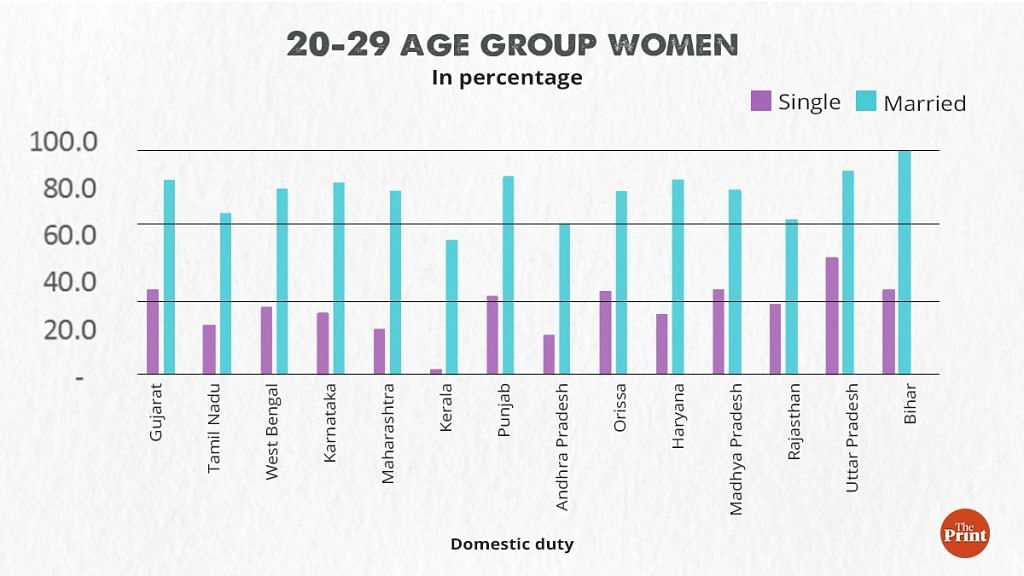

Over 72 per cent of young women in India were married in 2018-19. While over 15 per cent of single young women were involved in paid work in industry and services, less than half of that – about 7 per cent of married young women did the same. In contrast, nearly 80 per cent of married women were involved full time looking after their homes and families compared to around 32 per cent of single young women, the majority of whom lived with their parents.

What are the regional differences in the changes in the life trajectory of young women post marriage?

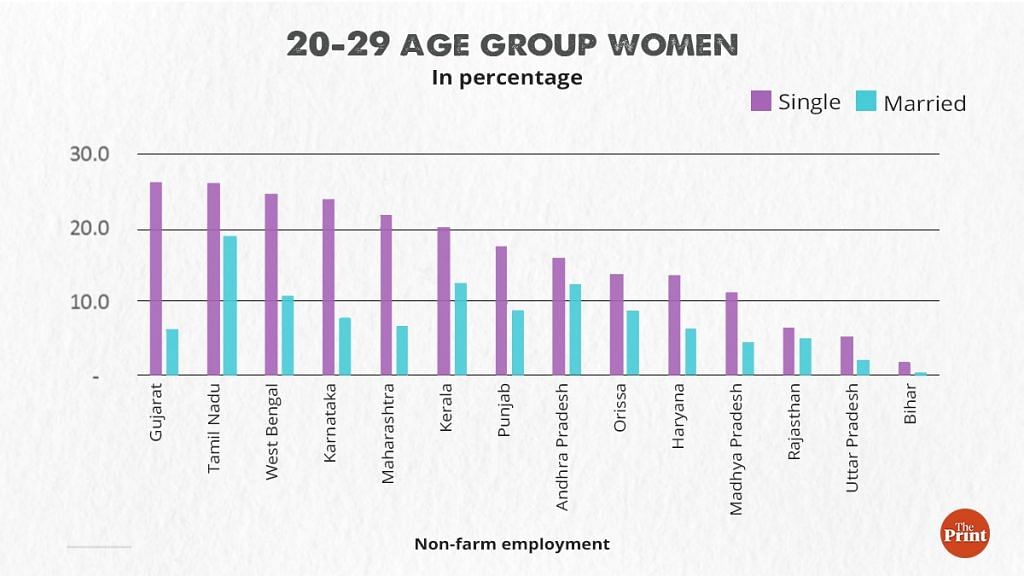

The highest proportion of single young women in paid work in industry and services (non-farm employment) were in Gujarat and Tamil Nadu. When it comes to married young women, while Tamil Nadu continues to have the highest proportion of married young women in non-farm paid work, only 6.5 per cent of married young women working in Gujarat was in industry and service sectors, making it among the states with the least proportion of married young women in non-farm work. In, Karnataka, Maharashtra, and West Bengal, too, the gap between the proportion of single and married young women in paid work in the non-farm sector is high. In contrast, like Tamil Nadu, in Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Odisha, there is less difference among the proportion of single and married young women in non-farm work. In Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, almost all young women – both single and married – are economically inactive in non-farm sectors.

The highest proportion of single young women in paid work in industry and services (non-farm employment) were in Gujarat and Tamil Nadu. When it comes to married young women, while Tamil Nadu continues to have the highest proportion of married young women in non-farm paid work, only 6.5 per cent of married young women working in Gujarat was in industry and service sectors, making it among the states with the least proportion of married young women in non-farm work. In, Karnataka, Maharashtra, and West Bengal, too, the gap between the proportion of single and married young women in paid work in the non-farm sector is high. In contrast, like Tamil Nadu, in Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Odisha, there is less difference among the proportion of single and married young women in non-farm work. In Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, almost all young women – both single and married – are economically inactive in non-farm sectors.

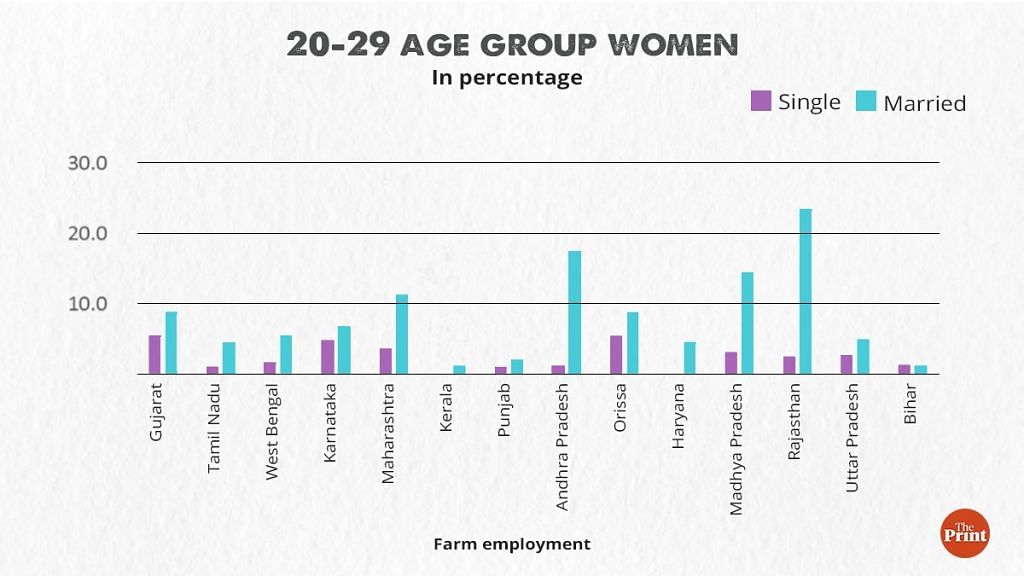

Surprisingly, young women, single or married in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar do not seem to work in a large proportion on farms either (Figure 2). In Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Andhra Pradesh, a significantly higher proportion of married young women work on farms. In prosperous states of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Punjab and Haryana, the same proportion is well less than 5 per cent.

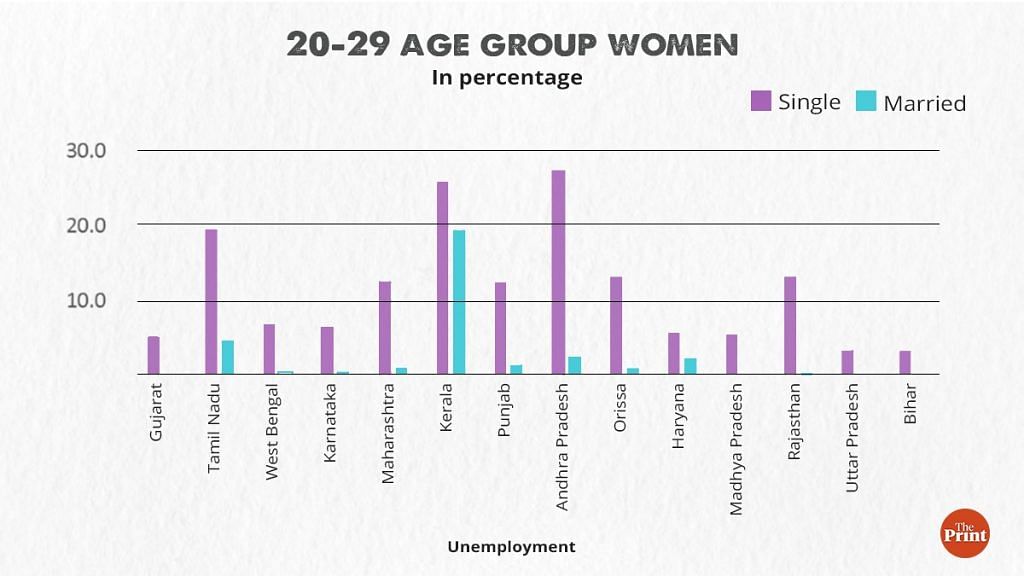

The obvious question is if young women, especially married, were not in work, how many of them were looking for it? (Figure 3). Among married young women, unemployment is high only in Kerala. In contrast, in states such as Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and Rajasthan, while unemployment is relatively high among single young women, it is low among married young women, suggesting a higher proportion of married women stop looking for jobs.

Also read: In India’s job market, women have higher exit rate, lower entry rate than men: Study

Why married women don’t work

This brings us to the last and the most widely discussed reason for the low level of economic participation among Indian married women – household work and child care. (Figure 4). Kerala has the least proportion of women who were occupied full time in domestic responsibilities, while in Bihar, almost all married young women – 96.5 per cent – were economically inactive in 2018-19.

The existing research has suggested several potential policy actions to raise women’s employment, both from the demand side – creating jobs that are suitable for women – and the supply side – raising women’s ability to participate in economic opportunities. The former includes providing impetus to sectors that are considered women-friendly and legal provisions such as job quotas for them. The latter includes raising girls’ aspirations and easing gender norms via school-level intervention, proactively providing information about job opportunities, exposure to female leaders, improving women’s commuting mobility, and affordable childcare. This is another factor that may be hampering women’s participation in paid work that has received less attention in this debate.

A higher proportion of married women in paid work in India face domestic violence compared to women who are not in paid work. Our estimates based on the 2015-16 data from the National Family Health Survey show that among young married women of 20-29 years of age in India, 34 per cent of those who are in paid work faced domestic violence from their spouse during the 12 months leading up to the survey compared to 24 per cent of those who are not in paid work.

Higher domestic violence faced by married working women is a combination of two factors – the backlash from their spouses as well as women’s own guilt over working outside, which makes a higher proportion of married working women accept and justify domestic violence, as the first two authors of this article show in a paper forthcoming in Feminist Economics.

Perhaps the best chance to change the attitudes on gender norms is to intervene in the early phases of life, especially during the adolescent years. It is only then that many young women in India will have more choices about how they wish to lead their lives.

Vidya Mahambare is Professor of Economics, Great Lakes Institute of Management. Sowmya Dhanaraj is Assistant Professor of Economics, Madras School of Economics. Sankalp Sharma is a post-graduate student, Madras School of Economics. Views are personal.