The last thing Modi and Kejriwal supporters want to hear is how similar their leaders and their decisions were. But there was a whole host of similarities.

It is a cruel coincidence that in the same week that we were head-butting over the one year anniversary of the disruptive decision of demonetisation, we are also poring over data to determine if the odd-even exercise worked the last two times it was implemented – in January and April 2016.

The two trending hashtags this week – demonetisation and odd-even – what could possibly be similar about them?

The last thing that the supporters of both Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal would want to hear is how similar their leaders are. And that is precisely why it is so tempting to expand the idea.

But this isn’t an essay about their egos or personality-driven leadership. This is about two decisions that have very similar mythology and optics built around them. They are similar in the manner in which the leaders took the decisions, marketed them, and how the Indian public received them.

Both demonetisation and odd-even challenged the ‘business-as-usual’, and caused tremendous discomfort to the people.

Both were deeply political decisions masquerading as technocratic, out-of-the-box solutions. They were meant to shore up the political image of two leaders who wanted to be “seen” to be doing something.

At the heart of both decisions was a messianic zeal to clean up a very dirty problem. Both the measures came from a deep resentment toward an entrenched class of people who have amassed wealth and comfort without a care for how corrosive their lives have become.

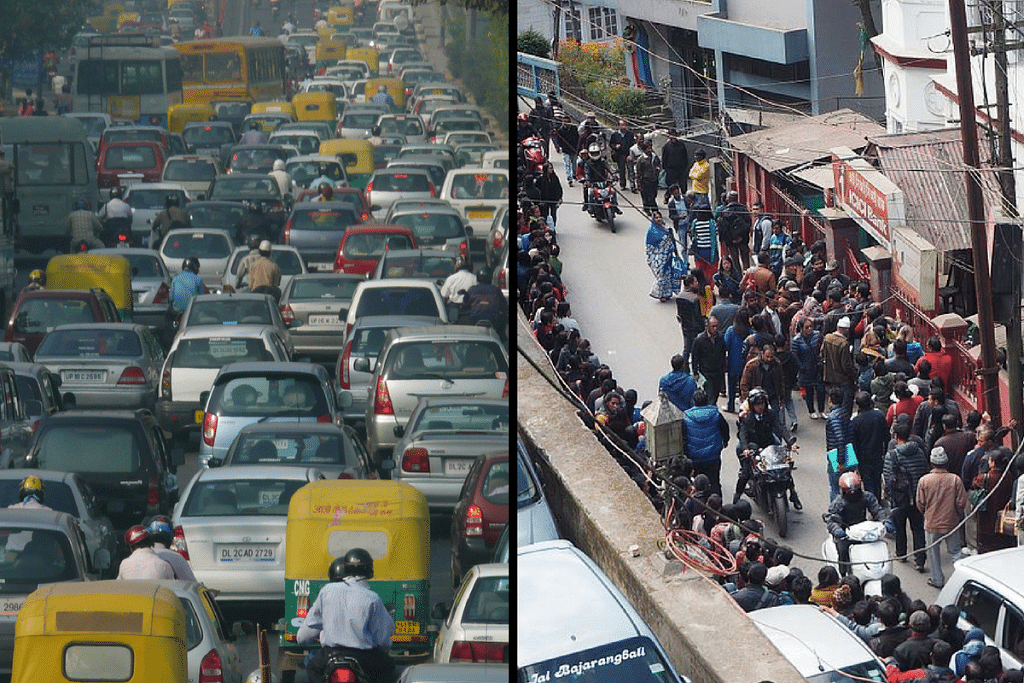

At one stroke, both the decisions reduced everybody to the same level of inconvenience – no matter how wealthy and privileged you were. The government stripped you of your accumulated social and financial capital. Everybody was now equal in misery – in bank queues and in their daily commute.

It created an imagined sense of collectivism, working towards the shared goal of a better life that will be hand-delivered by the leaders.

Both measures were introduced, sustained and celebrated in the face of mounting statistical evidence that they may not have worked, and that they did not address the core problem (real generator of black money and toxic air respectively).

Both challenged the cult of expertise – i.e. the exalted kingdoms of economists and environmentalists. It split these communities in two. Some economists hailed demonetization; others produced government data to show that cash formed merely 4.9 per cent of undisclosed wealth. Some environmentalists endorsed odd-even as the best example of citizen participation, others quoted studies to show that cars contribute only 10 per cent to Delhi’s air pollution.

As leaders, both used citizens’ experiences to create a larger narrative around individual sacrifices meant for public good. Everyone was deemed a ‘sinner’, and had to undertake penance.

Seeing public anger build up, Modi quickly elevated their suffering to the sacrifices expected in a ‘yagya’ (purification ritual). When you hear the word ‘yagya’, it automatically brings to mind penance and hardships undertaken to bring about social repair. In radio ads, Kejriwal said: “I know it will be hard, but to reduce pollution, we have to suffer a little.” He said he had “no choice”, and asked the people of Delhi to “adjust”.

In carefully choreographed television images, Modi’s old mother was shown walking into a bank to change her money. His party workers served juice and laddoos to the people standing in long queues. Similarly, photographers clicked Kejriwal as he carpooled, and his ministers travelled by Metro. His volunteers presented roses to commuters driving the wrong vehicle.

Both leaders worried excessively about the political capital they could lose by causing pain to the poor, common people. Modi invoked schadenfreude to assuage the poor. In the case of odd-even, it is now the two-wheeler commuters who Kejriwal wants to spare.

Did demonetisation kill black money? Ask the government this question, and the tangential answer is, “oh but digital transactions went up”.

Did odd-even reduce pollution? The answer is, “but the roads were unclogged, it was a dream to drive in Delhi.”

There is, however, one difference.

In the end, demonetisation was a one-time affair. But the odd-even measure now threatens to return in its third avatar – if the quixotic NGT obliges the Delhi government’s appeal on Monday.