Exploits of a few daring pilots of the IAF have largely gone unrecognised in the 1947-48 war.

Air Marshal Randhir Singh, one of the last of the surviving aerial warriors of the Indian Air Force who saw extensive action during the 1947-48 conflict with Pakistan, passed away on 18 September in Chandigarh aged 97, 71 years after he made his daring forays into the Valley in a Tempest fighter from 7 Squadron.

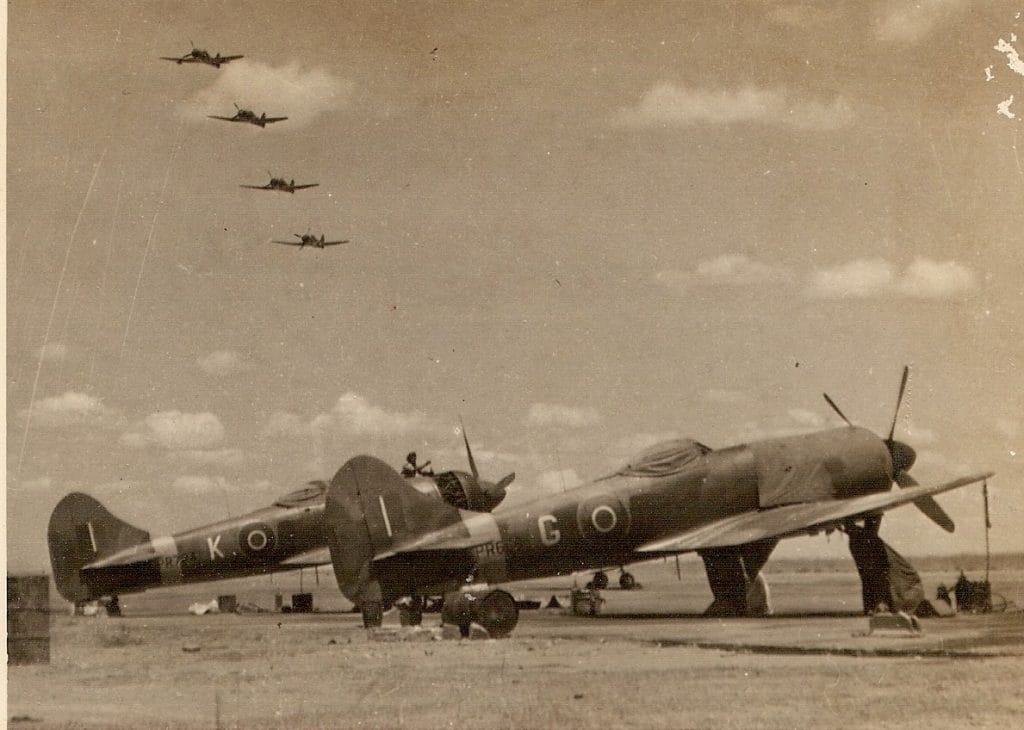

He flew 170-180 hours between October 1947 and December 1948, among the most that any IAF pilot flew on fighter aircraft during the conflict. I would reckon that Micky Blake, the energetic flight commander of 8 Squadron, one of the three Tempest squadrons in action during the war, was the only one who may have matched his flying effort.

Recce of Srinagar-Baramulla road

However, before he went into action on 27 October 1947, a fair amount of aerial activity had already taken place. Following the signing of the Instrument of Accession between Maharaja Hari Singh and the GoI on 26 October 1947, there was some hesitation to airlift troops into the Kashmir Valley because of conflicting reports about the distance of the raiders from Srinagar airfield.

Also read: When Lt Col Adi Tarapore showed rare courage and Army ate Pakistani sugarcane in 1965 war

Wing Commander H.N. Chatterjee and Flight Lieutenant N.K. Shitoley were summoned to Delhi in their slow-moving Oxford recce aircraft from Ambala, and briefed to carry out a recce of the Srinagar-Baramulla road to ascertain whether there was a window of opportunity to reinforce the airfield before the raiders came within striking distance. So, off they went, refueling at Amritsar and flying across the Pir Panjal ranges before confirming to Delhi that the raiders were still at Baramulla.

Reassured that Srinagar airfield would be clear, the airlift of the 1st Battalion of the Sikh Regiment and 161st Infantry Brigade commenced on 27 October 1947 by Dakotas of No. 12 Squadron and a hastily assembled volunteer force of civil Dakotas, an operation that is well-chronicled in the annals of contemporary Indian military history.

Search and Strike Mission

By then, having whetted their appetite for loot and plunder, Akbar Khan’s tribal Lashkars commenced their advance towards Srinagar on foot and on vehicles, unopposed by J&K State Forces, which had capitulated after a spirited initial resistance. This was when two Spitfires from Ambala joined 1 Sikh at Srinagar before noon in an unheralded moment of jointmanship.

After refuelling from barrels filled with borrowed fuel from the Dakotas, which were streaming in through the day, the pilots, Flight Lieutenant Roshan Suri and Flying Officer J.J. Bouche, were briefed with whatever intelligence was available. Getting airborne soon after, they carried out repeated strafing runs over the tribal columns in what would be called today as Search and Strike Missions. In effect, this was the first time that the seeds of doubt were laid in the minds of the raiders that they were in for a serious riposte.

Also read: How India asked for trouble in 1962

Joining them over the Baramulla-Srinagar highway was Flight Lieutenant Randhir Singh from No. 7 Squadron (Battle Axes) on a recce mission in his Tempest fighter to ascertain the feasibility of adding aerial firepower and cause further attrition on the raiders. He was back in action the next day with his number two on a similarly long mission from Jammu (250 km + one way) with a full load of rockets and guns. The Spitfires and Tempests flew tirelessly to slow down the raiders and allow 1 Sikh to concentrate forces and set up defensive positions around Srinagar.

Why Srinagar airfield didn’t fall

The road distance from Baramulla to Srinagar airfield is 70 km and it should have taken the raiders not more than 48-72 hours to get to the outskirts of Srinagar. All known timelines indicate that the moment the Pakistan Army came to know of the accession, they urged the raiders to advance towards Srinagar.

If the advance commenced on 27 October, it is now clear that there were two principal reasons because of which they could not contact the outskirts of Srinagar: Blocking positions set up by 1 Sikh, and the few but effective Spitfire and Tempest missions from 27 October to 2 November. By then, 1 Sikh was reinforced by 4 Kumaon and the stage was set for the decisive Battle of Badgam where Major Somnath Sharma was posthumously awarded independent India’s first Param Vir Chakra.

What has not been adequately chronicled is that the two Spitfires from Srinagar carried out repeated missions against the attacking raiders who had at one time threatened to overwhelm the 4 Kumaon positions. Had it not been for the heroic resistance offered by the Kumaonis and the air support from the Spitfires, Srinagar airfield may well have fallen on 3 November.

Also read: Untold heroism story: How IAF stayed up on eve of Air Force Day to save journalist’s life

Attention shifts to Poonch

By the first week of November, the IAF had a few Spitfires and two Tempest squadrons in the fray with 10 Squadron joining in. That meant that when 161 Brigade was ready to launch an offensive at the Battle of Shalateng on 7 November, the IAF was already in action all day with up to four aircraft over the Tactical Battle Area (TBA) as the area of operation expanded with raiders fleeing through the Srinagar-Baramulla-Uri-Domel road. By 10 November, the threat to Srinagar had passed and the raiders now shifted their attention to Poonch.

The contribution of the IAF in the relief of Poonch, attacks on Skardu, landings and airlift of Gorkha troops for the relief of Leh, and fighter attacks during the opening of Zojila Pass are well-documented. The exploits of Air Commodore Mehar Singh and Air Chief Marshal Hrushikesh Moolgavkar are now IAF folklore, but those of a few other daring pilots of the IAF cannot go unrecognised.

Arjun Subramaniam is a retired Air Vice Marshal from the IAF and a Visiting Professor at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University.