The conservation of wildlife in its habitat has assumed greater importance because of Covid-19, as studies indicate that 60 per cent of Emerging Infectious Diseases — such as HIV, Ebola, SARS, Covid-19 — affecting humans are zoonotic. Approximately 72 per cent of these originate in wildlife. Wildlife habitats, which include Protected Areas and other categories of landscapes rich in wilderness, are also important life-supporting systems that play a critical role in ensuring food and water security, climate change resilience, and natural hazard regulation, among several other ecological, economical and cultural services.

Usually, when we think about wildlife, we do not think beyond Protected Areas (PAs), or areas declared as Wildlife Sanctuary and National Parks under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 (WPA). This is one of the reasons we are still in the process of declaring new PAs. New categories of PAs such as Conservation Reserve and Community Reserves were inserted into the WPA in 2002. The Aichi Target 11 Convention on Biological Diversity indicates that by 2020 at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water, and 10 percent of coastal and marine areas important for biodiversity and ecosystem services, should be conserved through PAs and other effective area‐based conservation measures. As per the National Biodiversity Targets under the convention, India was supposed to bring 20 per cent of the country’s area, which is rich in biodiversity and ecological value, under conservation by designating them as PA, and undertaking other conservation measures.

Protected Areas are not sufficient

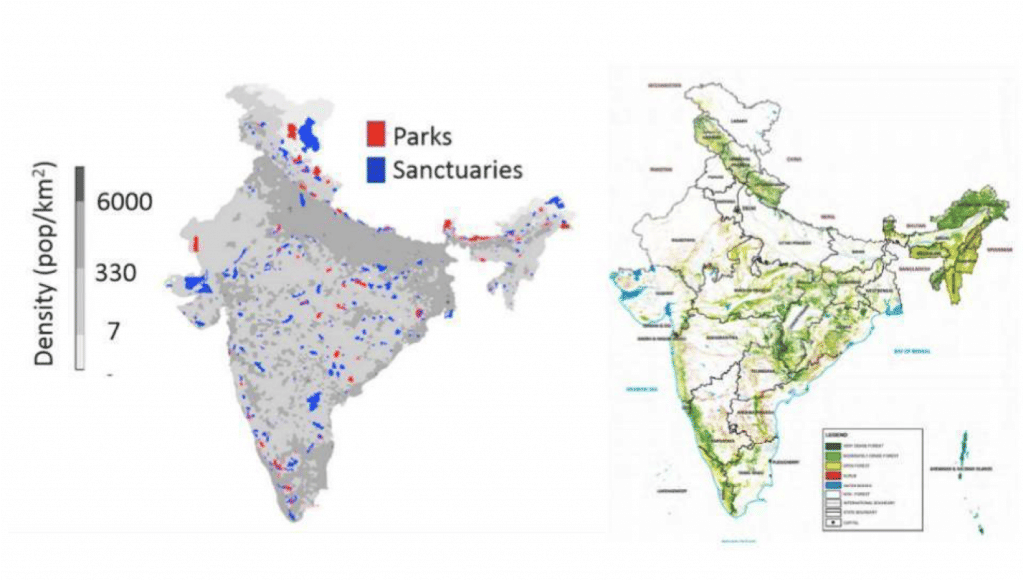

The standard approach to wildlife conservation in India focuses on saving particular species from extinction, using PAs as one of the tools. As of March 2020, India has managed to add 5 per cent of its geographical area under PA, spread over 903 Protected Areas, including 101 National Parks, 553 Wildlife Sanctuaries, 86 Conservation Reserves and 163 Community Reserves. Though the number may appear high, many of these PAs are very small in size.

For instance, the Mahavir Swami Wildlife Sanctuary in Uttar Pradesh is only 5.4 square kilometres (sq.km.) big, while Maharashtra’s Mayureshwar Supe Wildlife Sanctuary is 5.14 sq.km. in size, and Himachal Pradesh’s Renukaji Wildlife Sanctuary is a mere 4 sq.km..

According to a report, nearly one-third of PAs in India are less than 10 sq km and the average mean size of PAs in India is dismally small (~262 sq.km.) as compared to those in Africa or North America.

Most PAs, in reality, are administrative boundaries created out of convenience, and therefore cannot be treated as inclusive of all wildlife habitats in the country. In fact, declaration of any PA and its buffer zone (such as Ecosensitive Zones) is a political process, and the declared boundaries do not necessarily overlap with actual ecological needs. Furthermore, strong protection within PAs has meant that they have exceeded their carrying capacity, forcing wildlife to move outside their administrative boundaries. This makes the protection of habitats outside PAs even more important.

Also read: India kept improvising during coronavirus. Age of Pandemics needs a new public health law

Importance of State-owned Territorial Forests

Almost 20 per cent of India’s geographical area is under some kind of conservation planning, and is managed for biodiversity conservation, which includes a large tract of lands managed by State Forest Divisions and private owners apart from the Protected Areas. These forests, referred to as Reserve Forest (RF), State Forest (SF), Protected Forest (PF) etc, are regulated under Indian Forest Act, 1927 and various other state legislations.

The forests owned by the State are often referred to as Territorial Forests (TF). They harbour nearly all of India’s 36 endemic mammals and act as important connectors with the more strongly guarded, but scattered, network of PAs across the country. At the same time, some TFs are also one of the most human-dominated wildlife areas, prone to heightened human-wildlife conflict and poaching. Despite their valuable ecological importance, TFs remain neglected under India’s patchwork of laws.

India’s PAs, which are designated under the Wildlife Protection Act (WPA), 1972 have received increased protection, better resources and the benefit of specialised scientific training of wildlife. On the other hand, TFs, which include Reserve Forests, are governed by officers of state forest departments using the vehicle of the colonial Indian Forest Act, 1927. These departments have historically been more concerned with the extraction of commercially valuable forest produce, with little concern for wildlife protection.

Except for cases of poaching, the WPA provides very limited protection to wildlife habitats inside TFs. For instance, any activity involving the use of PAs requires the prior recommendation of the National and State Boards of Wildlife (NBWL/SBWL). However, no such recommendation is required for wildlife habitats outside PAs, although they may be just as rich in wildlife or important wildlife corridors. Except for the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA), which is responsible for protecting tiger reserves, it is unusual for agencies under the WPA to intervene in issues related to wildlife habitat protection in areas like TFs.

Also read: India’s healthcare workers are the most vulnerable, but there is no framework for their health

The way forward

The future of wildlife conservation in India depends on how well governments are able to manage TFs. This requires a systematic and scientific approach and sufficient resources. The working plans of all TF divisions in India should compulsorily include wildlife conservation plans, efficient monitoring mechanisms and measures for mitigating human-wildlife conflicts.

Such comprehensive management requires an independent expert body at the national level, that can assume primary responsibility for the protection of wildlife habitats, and advise central and state governments on all matters related to wildlife management and human-wildlife interaction.

The National Wildlife Protection Authority (NWPA), if established, should have powers similar to the NTCA, but with wider jurisdiction for the protection of all scheduled wildlife species and their habitats, irrespective of the ownership of land. The NWPA should have at least 10 regional headquarters representing each biogeographic zone.

The authority can also provide a breather to toothless bodies like the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB), which cannot exercise independent authority to curb poaching but are reliant instead on state forest officers and the police. Similarly, other bodies like the National and State Biodiversity Boards under the Biodiversity Act, 2002, and the National and State Boards of Wildlife (NBWL/SBWL), which are essentially advisory bodies, must be made part of this independent authority. The NTCA can be made a part of it, and more such bodies could be created to oversee different identified priority species.

The NWPA should also have the power to approve working plans and other management activities proposed by forest divisions. It must ensure their compatibility with regional wildlife requirements, prevent ecologically unsustainable land use, facilitate framing of guidelines, encourage research, organise training of frontline staff in the management of human-wildlife interactions, and most importantly facilitate community-driven conservation efforts.

Towards a Post-Covid India is a briefing book with 25 legal reforms recommended by the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Join a series of conversations — ‘Law with a Difference’ — on the book. ThePrint is the digital partner. Read all the articles here.

Vidhi's briefing book proposes creating a National Wildlife Protection Authority to protect wildlife, their habitats & reduce conflicts. Join Vidhi's discussion on the same on July 22, 5:30 PM- part of the #LawWithADifference series with @ThePrintIndia as digital partner. THREAD pic.twitter.com/iwfPjb0j2Q

— Vidhi Centre For Legal Policy (@Vidhi_India) July 18, 2020

The author is an award-winning wildlife conservationist and a Senior Resident Fellow at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Views are personal.