In most societies around the world, women participate in politics at lower rates than men. Research shows that women also have a distinct set of economic policy preferences, prioritising government-led taxation and redistribution of wealth more than men. Scholars have long debated whether cultural or economic factors explain this gender gap in political participation and economic policy preferences. We argue that this debate has missed a central point: cultural norms themselves systematically structure women’s and men’s economic opportunities and, therefore, incentives to engage with politics.

In a recent paper, we focussed on a particular set of cultural norms related to inheritance and lineage, which determine which gender owns and manages wealth. To determine the effect of lineage norms on women’s political participation and policy preferences, we conducted a large-scale study in the northeastern state of Meghalaya, which is home to the matrilineal Garo, Khasi, and Jaintia tribes, who together make up approximately 91% of Meghalaya’s tribal population. In these matrilineal tribes, property passes directly from mother to daughter. Living side by side with these matrilineal tribal groups are patrilineal communities, Mizos and Hmars — where inheritance is traced from father to son. Fourteen percent of Meghalaya’s population is non-tribal.

The Meghalaya example fits with our theoretical analysis of matriliny, wherein men retain formal positions of power such as political office because of broader patriarchal structures that persist in society. Despite exclusion from positions of authority, however, matrilineal women are active political participants: attending meetings, voicing concerns, and organising to resolve socioeconomic problems.

In Meghalaya’s capital, Shillong, matrilineal and patrilineal communities live in close proximity, share analogous political institutions, subscribe to broader patriarchal structures, avail of common welfare state policies, and face comparable local economic milieus. The primary difference follows cultural norms about lineage, which determine wealth ownership and control. We leverage this variation to study whether culturally sanctioned wealth inequities drive the political economy gender gap.

We find that in societies where wealth passes from mother to daughter, women are more politically active than men and the gap between female and male policy preferences disappears. Here, women’s confidence in their capacity to leverage resources independent of state intervention leads them to embrace a much larger set of political roles and policy options, in line with men in patrilineal societies. These findings suggest that improving women’s political representation requires not just increasing female economic opportunities, but also changing social norms to support female access to and control over wealth.

Also read: 77% women in Panchayati Raj Institutions believe they can’t change things easily on ground

Wealth increases political engagement

To reach these conclusions, we conducted an in-person, representative survey with several embedded experiments—in addition to extensive qualitative research—in Meghalaya’s matrilineal and patrilineal tribes. We first examined whether political engagement varies as a function of respondents’ gender and matrilineal/patrilineal group status. Being politically engaged requires resources, so we expected that women in matrilineal communities would be as politically engaged as their male counterparts in patrilineal communities. Indeed, we found that when women have economic power, the gender gap in participation we observed in patrilineal groups flips. Traditional wealth owners—patrilineal men and matrilineal women — are more politically engaged than culturally excluded genders (patrilineal women and matrilineal men, respectively).

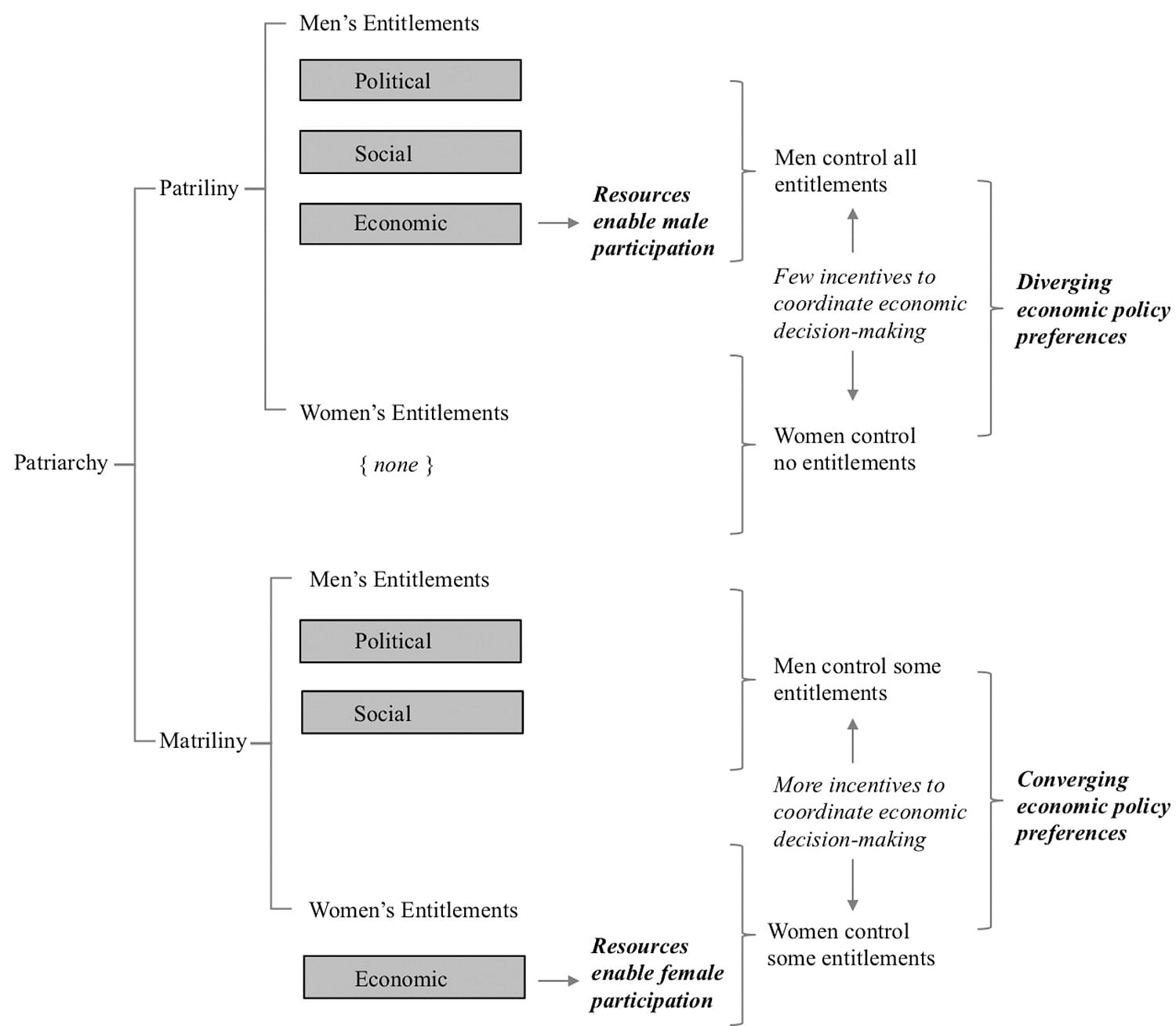

The reversal of gendered entitlements to resources in matrilineal societies is radical because it occurs within larger patriarchal systems where men hold social and political entitlements. As a result, lineage norms not only enable women’s political engagement but also alter incentives for gender-based coordination within families.

We conducted a vignette experiment to see whether lineage norms help explain the gender gap in preferences about redistribution. We varied whether expressing support for the welfare state would entail an explicit, personal cost for the subject or not. We expected that individuals would be less likely to support welfare policies if and when they require giving up wealth the respondent controls. Our findings support this theory: preferences for costly redistribution diverge in patrilineal groups but converge in matrilineal groups. Men—who exclusively own and manage wealth—are more likely to oppose costly redistribution. Women, excluded from wealth ownership and management, remain cost insensitive.

We probed the mechanism for this matrilineal convergence in two additional experimental questions. We found that in matrilineal communities, where both genders are involved in wealth management, men and women had similar preferences about redistribution policies that would affect their shared wealth. Whereas in patrilineal communities where women are less likely to either control or manage money, men’s and women preferences about state-led redistribution diverged.

Figure 1. Cultural resource entitlements, participation, and political economy preferences

Also read: Covid decisions across the world being made by men, not women, study finds

Control wealth, oppose welfare policies

Finally, we conducted an innovative behavioural experiment to see whether respondents were willing to take action to express their preferences about redistribution. This experiment linked participation to preferences by asking participants if they were willing to fill out and send a pre-stamped postcard stating their preferences about redistributive policies. We expected that lineage norms would predict both — which gender would be most likely to participate, and the content of the preferences they express. In patrilineal groups, we found introducing an explicit cost made men more likely to participate to oppose welfare policies. In contrast, among matrilineal groups it was women who were more likely to participate to express opposition to welfare state policies when informed about their cost.

Overall, our paper demonstrates that wealth ownership and control norms can explain the gender gap in political participation, in preferences about redistribution, and willingness to act to advance political preferences. These findings have important implications for societies around the world, where broader cultural norms defining women’s financial agency—including those governing investments in education, skills accumulation, occupational specialisation, remuneration, career advancement, and provision of care — continue to systematically limit women’s economic prospects.

Our study suggests that increasing women’s economic opportunities alone will not fundamentally change political representation. Improving employment opportunities or property rights for women in conservative cultures can generate backlash—a phenomenon documented in settings from rural India to Ethiopia. While improving economic inclusion is vital, policy makers should anticipate backlash, build mechanisms to protect the vulnerable, and incentivise egalitarian negotiations between status quo and policy beneficiaries. Work to change social norms that prevent women from equally accessing and controlling wealth is imperative for political equality.

Rachel Brule is Assistant Professor of Global Development Policy at Boston University. Nikhar Gaikwad is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Columbia University. Views are personal.

This article is a summary of the authors’ paper, first published in The University of Chicago Press’ The Journal of Politics, and includes edited excerpts. Read the full paper here.

(Edited by Prashant Dixit)