A slim, sickle-shaped knife hidden between the lower jaw and the cheek, the presence of scattered bajra grains on the floor of a burgled house, false coins secreted in the inner front flap of the loincloth—these are just a few details colonial-era policemen were expected to remember when they were in pursuit of criminal tribes, in order to identify them correctly.

It is well known that the British colonial administration in India marked out certain communities as ‘criminal’ by passing the Criminal Tribes Act (CTA) in 1871 (final version enacted in 1924). What is less known is how they went about implementing it— who were tasked with identifying these groups? What tools did they use for identification? How was this knowledge disseminated among them?

While the laws provided the theoretical and legal framework to impose control on the suspected groups, the men tasked with executing them—the police—required more practical guidelines. Compiled by experienced officers in the force, the guidelines were in multiple regional manuals and they provide a fascinating window to the methods used by the police to scrutinise, identify and regulate groups deemed ‘criminal’. Though the century-old manuals are no longer in use, it may be pertinent to ask if the ideas they endorsed have been eradicated from the official psyche?

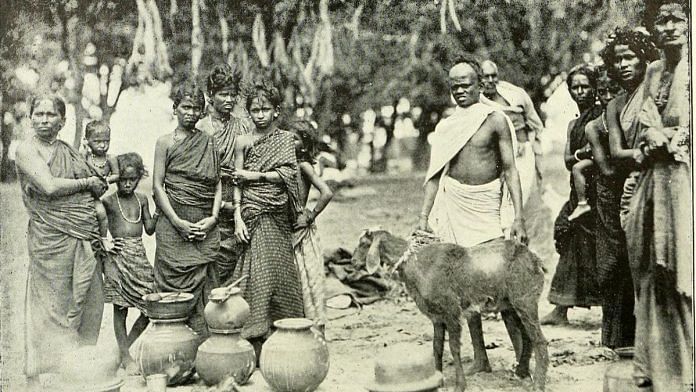

In these handbooks, all available information about ‘criminal’ communities in a region was distilled into a single volume, which were then made available to the police at the local level. Photographs were also included. Maximum attention was devoted to peculiarities of appearance, modes of communication and the method of committing the crime.

Physical descriptions emphasised peculiarities in appearance, which could aid the police in detection. British officer F.C. Daly’s manual for Bengal (1916) noted that every Marwari Bauriya was branded with a hot iron usually near the navel, which left ‘large and unmistakable’ scars. The women had specific tattoos patterned on their faces. E.J. Gunthorpe (1882) explained that the Kunjurs operating in the Deccan could always be recognised by the dress (short lehenga) worn by women, due to which they were known as ‘Oonchalainga Kunjurs’.

Also read: How a brutal murder in 1852 convinced the British to make India’s Hijra community ‘extinct’

Knowing the tribes

English professor and author Henry Schwarz has shown that a core feature of police manuals was the inclusion of the thieves’ special lingo. Simply knowing the special argot could lead to conviction as it linked the individual to the membership of a group under suspicion. Daly provided examples of Jharkhand’s Bedia tribe jargon— theft- beli, police- kakaro, hiding- chappoki. When any member of the Tuntia Musalman gang got separated from the main body during the retreat from a dacoity, he indicated his whereabouts by imitating the howling of a jackal. Non-verbal modes such as gestures and signs were also specified— Bhamptas put their hand up to the face and jerked the elbow upwards to indicate danger. A ‘complete dictionary’ of terms used by the ‘criminal tribes’ of the Punjab was compiled by Daroga Mohammad Abdul Ghafur of the Punjab Police (1879).

A major portion of each entry in the manual was devoted to modus operandi of the concerned tribe. Andrew J. Major points out that the perception of the entire caste as ‘criminal’ was the bedrock here as the transfer of skills from one generation to the next meant that specific types of crime were connected to specific ‘criminal’ communities. Daly described a wide variety of criminal operations from railway theft (Bhamptas, Barwars, Sanaurhiyas), swindling (Chain Chamars, Jadua Brahmans, Muzaffarpur Sonars), river crime (Banfars, Gains, Sandars), counterfeiting coins (Chhapparbands) to theft and burglary (Bedias, Palwar Dusadhs).

In the case of burglaries, the police were trained to recognise the way different tribes went about house-breaking. Frederick S. Mullaly of the Madras Police Department noted that Telugu tribe Wudders used a crowbar to make a breach at the back or side of the house near the foundations. A breach in the wall at the side of the door-frame in line with the latch would implicate Bowries or Budhucks, according to E.J. Gunthorpe of the Berar Police. The Dhekarus did neither, but being blacksmiths, they forced the locks or removed the staples. To break down doors with a battering ram, Choto Bhagiya Muchis used ploughshares from neighbouring houses while Tuntia Musalmans preferred the dhenki (husking machine).

The manuals covered as wide a ground as possible so as not to miss any detail that might lead to the capture and arrest of the suspected groups. The presence of mustard seeds or bajra grains on the floor of the house that has been broken into, indicated the work of Bowries or Budhucks, stated Gunthorpe. These were gently thrown forward into the room prior to the break-in to learn the position of any brass or copper pots or boxes in the room. The noise of the seeds hitting against them indicated their exact location, thus showing the direction in which the objects could be reached without obstacles.

Not even something as innocuous as the roofing of a country boat fell outside the purview of these manuals. Daly categorised both Gain or Gayan and Sandar tribes as river dacoits but warned against confusing one with the other. He stressed that the distinctive roofing of their boats would give them away and provided photographs of both in his manual.

Also read: UP tops 2021 in crimes against Scheduled Castes, followed by Rajasthan, MP, says report

Endorsing prejudice throughout India

The manuals contained much advice on how a proper ‘search’ should be conducted. M.Paupa Rao Naidu’s manual specified that goods looted by the Bhamptas could be concealed within double-built walls, between beams or under the hearth in their homes. Bhampta men often secreted a curved knife in the hollow between the lower jaw and the cheek, which was used as an aid in railway thefts; Gunthorpe explained that to enable this, the gums were hardened by placing a lump of salt there day and night for some time. Body searches too needed to be thorough—in one case a Bhampta woman had a currency note of Rs 100 hidden under a bandage on her thigh. The woman deputed to search her had not opened the bandage till she was directed to do so by the police officer. Naidu also warned that Koravar and Bhampta women were adept at concealing small jewels in the ‘private parts’. The best way to find this out, he advised, was to make the woman jump, ‘so that the jewel may drop in the act of jumping’.

Gruesome examples of their ‘bestial’ nature were catalogued usually with the label ‘their atrocities’. The Mecca Mowallems were said to throw their victim overboard with a pitcher of water tied around his neck and they would leave him to drown. Among the Karwal Nats, both sexes were violent; and in their most savage moods, both would strip naked and gesticulate ‘indecently’ at those who opposed them. Binding the victims and applying burning torches to the face was believed to be the mark of dacoities committed by Choto Bhagiya Muchis.

Through all these details, the notion that entire communities could be ‘criminal’ and could be identified by a fixed set of characteristics, was repeated over and over again. This justified the conviction that the tribes deserved every bit of the stigma ‘criminal tribe’ tag entailed. It is important not to underestimate the role of colonial-era police manuals in the creation and perpetuation of such ideas. The manuals were circulated throughout British India, the authors quoted each other to justify their conclusions and their contents would have been reproduced in many later texts. Thus, prejudice against the ‘criminal tribes’ proved to be surprisingly enduring as it circulated widely throughout the subcontinent. Independent India has broken free of many of the pernicious vestiges of colonial rule. But the real challenge remains to decolonise the mind.

Dr Krishnokoli Hazra teaches History at the undergraduate level in Kolkata.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)