The UGC controversy is the latest arena where caste’s institutional machinery is being renegotiated—and where the state’s classificatory grid struggles to keep pace with the realities of Indian society. India must understand that caste has always been a technology of power.

Medieval precedents

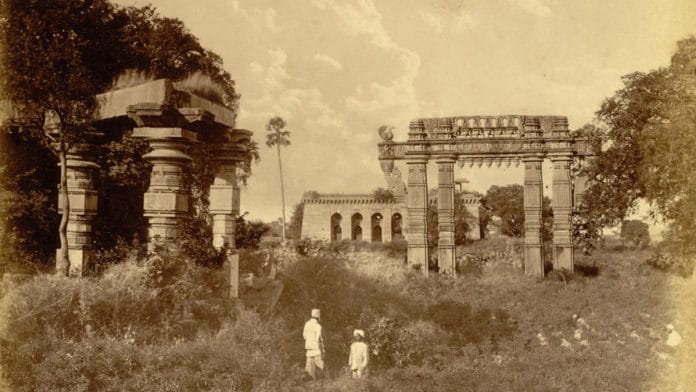

To understand this, let’s visit the world of medieval India. While the term ‘medieval’ might suggest barbarism or dogmatic adherence to scripture, the fact is that medieval India was, very much like today, a place of social, political, and religious churn. Power belonged to those who could mobilise land, labour, and patronage—not those who fit neatly into the categories of the Manusmriti. The Kakatiyas of the Deccan (c. 12th–14th centuries CE) and the Chola Empire (c. 9th–13th centuries CE) offer two different but equally revealing examples.

The Kakatiyas, as Cynthia Talbot shows in Precolonial India in Practice, lacked orthodox Kshatriya pedigree. (Indeed some of their inscriptions state that they were Shudras, technically the lowest in the four-caste Brahmanical order). Yet they built a durable kingdom by anchoring their authority in martial reputation and temple patronage. Consider, for example, this colourful description of the death of the Kakatiya king Mahadeva: “Having fallen asleep in a great battle on the two temples of a female elephant, this foremost among warriors awoke on the two breasts of a distinguished nymph of heaven.” And, from the same inscription, referring to Mahadeva’s descendant: “Having built a temple of Shambhu… She set up a linga… Having provided twelve houses and rich stipends, she supported twelve Brahmins, who resembled the Adityas.” (Epigraphia Indica III, pages 94–103). Temple patronage also allowed the Kakatiyas to make interventions in social hierarchies. Professor Talbot makes note of large numbers of women and shepherds who made temple gifts under the Kakatiyas, anomalous in the broader medieval scenario.

The Chola world, especially in its later centuries, demonstrates a different dynamic. During the height of the empire, many agrarian groups, particularly Vellala cultivators, rose up through both military service and temple patronage. (Indeed, some Brahmins considered the Vellalas ‘pure’ Shudras). But as political authority fragmented during the fall of the empire, coalitions of ‘middle castes’—including weavers, goldsmiths, warriors, and so on—formed collective assemblies to assert their status over landless labourers. They did this by taking control of temple offices and land rights, as well as assuming judicial and taxation functions.

Somewhat later, in the political churn of the late medieval period, military labour markets and migrations proved key. In Naukar, Rajput and Sepoy: The Ethnohistory of The Military Labour Market in Northern Hindustan, 1450–1850, historian Dirk Kolff shows how, especially in eastern Uttar Pradesh, Purbiya Rajput and Pathan identities were adopted by mercenary bands depending on their patron’s religion. The Gangetic mercenaries of the Gujarat Sultan, for example, might claim to be Pathans; in another season, if they were working for a Hindu Raja, they might call themselves Rajputs. Kolff points out that this was common even until the First World War, when young men might enter the recruitment office as a zamindar’s son and exit a Sikh.

The key point is that medieval India did not have a timeless Brahmanical order derived from scriptures. Every region had a political economy in transition, with caste being used as one of many hierarchical principles. For the Kakatiyas, caste status was claimed through martial and ritual institutions. For Tamil middle castes, it was collective organisation and temple institutions. For North Indian warrior groups, it was labour markets and mobility.

More recent anthropological and sociological work suggests that this dynamic endures. Susan Bayly’s Caste, Society and Politics in India emphasises that caste must be understood historically, not as a fixed essence. MN Srinivas’s Social Change in Modern India defines “dominant castes” as groups whose power derives from land, numbers, and political influence, not textual rank. Srinivas also describes the process of “Sanskritisation”, by which dominant castes adopt elite ritual behaviours as they rise in the hierarchy. These insights are essential to understanding the UGC controversy.

Also read: What a Tamil town tells us about votes, caste, and fraud in medieval India

New institutions, old dynamics

Today’s caste orders—especially with regard to OBCs—are evolving around contemporary institutions: Bureaucratic categories, reservations, and electoral arithmetic. At the same time, migrant labour networks, gig-economy platforms, and resident welfare associations are creating new hierarchies. Complicating this mosaic are new modes of ‘Sanskritisation’: Easier access to scriptures, gurus and pilgrimage infrastructure; broadcast media, and a roaring spirituality industry. All this is to be expected from a historical standpoint. What is less clear is how these map onto contemporary SC/ST/OBC categories. The state’s organisational schema does not capture this dynamic historical process, but it is certainly happening.

Christophe Jaffrelot’s India’s Silent Revolution, and later essays, document how technically OBC groups such as Yadavs in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, Jats in Haryana and western UP, Marathas in Maharashtra, and Vokkaligas and Lingayats in Karnataka have combined landholding and electoral leverage to wield enormous political power. Many also adopt martial genealogies, sponsor temples, or act as protectors or patrons—quite similar to medieval warrior castes.

Lingayat guru lineages, for example, descend from 12th century anti-caste movements in north Karnataka, though functionally they act similar to other landed Hindu sects. Meanwhile, the Thevar and Vanniyar castes in contemporary Tamil Nadu claim status from service under Chola kings. In recent months this status has been violently asserted by caste vigilantes against Dalits. However, arguably the majority of OBC groups remain landless and vulnerable, and continue to face discrimination and violence at the hands of both ‘dominant’ OBCs and ‘upper’ caste savarnas.

There is a clear gap, then, between what might be textually or bureaucratically expected of a varna and jati group and how it historically arrived at and performs its caste status in the Indian political landscape.

To return to the UGC guidelines: Right-wing critics have argued that the guidelines risk politicising campuses or enabling identity-based harassment against savarnas. From a historical standpoint, it can indeed be argued that some OBC groups wield the same (and sometimes more) electoral might than savarnas, particularly in university politics. At the same time, it is also true that many OBC students require further safeguards against caste discrimination, and that existing mechanisms to tackle caste-based violence have fallen short—even in ostensibly progressive states like Tamil Nadu. But from a historical standpoint, the deeper issue is not whether the guidelines go too far.

It is that caste continues to evolve functionally, while our official categories remain rigid. Caste is a historical technology of power, continually remade through the institutions that matter most at any given moment. Temple committees and properties were once an arena for this remaking; today, among other arenas, universities and bureaucracies are key.

Understanding and annihilating caste requires tracking and responding to these shifts. One of India’s deepest ancient dynamics can neither be denied nor regulated out of existence.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of ‘Lords of Earth and Sea: A History of the Chola Empire’ and the award-winning ‘Lords of the Deccan’. He hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti and is on Instagram @anirbuddha.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

It’s nfortunate that this kind of historical work isn’t included in school curricula. For decades, Marxist historians dominated Indian education, presenting a distorted view of Hindu history through ideological lenses rather than evidence.

What’s encouraging is that people like Kanisetti are now turning to primary sources—inscriptions, temple records, and indigenous materials—to present a more accurate picture of India’s past. This evidence-based approach, drawing directly from historical artifacts rather than imposed frameworks, is exactly what Indian historiography needs.

We need more of this work in mainstream education to counter the falsifications that have shaped public understanding for too long

Very well written and objective.