The Bharatiya Janata Party’s success in an assembly election is determined, above all, by its ability — or inability — to make ideological issues salient. Bihar is the latest example.

In phase 1, where material issues predominated, the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) won less than a third (29.6 per cent) of the seats, whereas the Mahagathbandhan (MGB) won more than two-thirds (67.6 per cent) of the seats. This was the phase where Tejashwi Yadav’s agenda of kamai (employment), dawai (medicine), padhai (education), sichai (irrigation) and mehangai (price rise) were foregrounded. The MGB assiduously avoided getting baited into ideological contestation with the BJP, and reaped the electoral dividend.

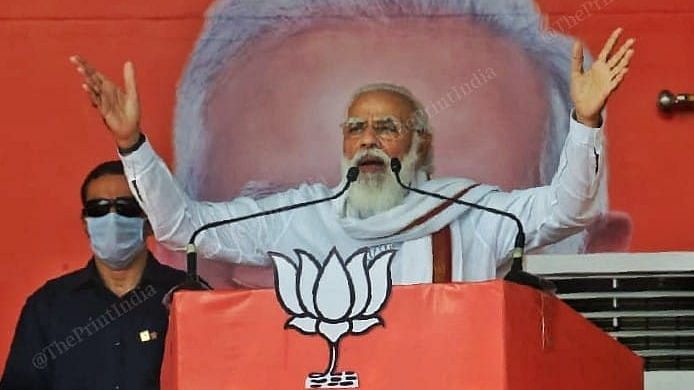

In contrast, the ideological issues became most potent in phase 3 of the election. This phase covered the areas with the highest Muslim population (Seemanchal, Kosi, and Mithila). It was this phase where Prime Minister Narendra Modi claimed that the “opponents of Bharat Mata are uniting” who “don’t like to hear Jai Shri Ram”. The rallies of the PM were also most effective in this phase, according to an analysis by Hindustan Times.

Moreover, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath too was deployed in the third phase to bring up the Citizenship Amendment Act and National Register of Citizens (CAA/NRC) and the threat of ‘Muslim infiltration’. And it was this phase where the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) also contested, partly on its vocal opposition to CAA/NRC inside and outside Parliament. Perhaps even more crucially, this was the phase where the BJP ratcheted up its ‘jungle raj’ and ‘Yadav raj’ rhetoric, which found more resonance as the prospect of an RJD victory became more real. The MGB was squeezed in this phase, winning just under 27 per cent of its seats. Unsurprisingly, the big winner of the third phase was the NDA, winning more than two-thirds (66.75 per cent) of the seats, which powered it to a narrow victory.

These results fit into a larger pattern. The BJP’s electoral success is predicated on its ideological dominance, and this theme of ideological salience explains its successes and failures over the last six years.

Also read: What makes Modi’s BJP invincible? The cynicism that India is dead

Challenger BJP vs Incumbent BJP

The BJP’s performance in state elections in the Modi era can broadly be divided into two categories: performance as challengers and performance as incumbents. The party manages to win handsomely as a challenger, often aligning with non-dominant castes to mount an attack on existing power equations in the state. As an incumbent, however, the BJP has had only a modest showing. While it has managed to hold on to states such as Gujarat and now Bihar, defying anti-incumbency of many election seasons, their performance has only been a poor shadow of their otherwise feted electoral dominance.

Analysts have argued that a multiplicity of factors are behind the BJP’s lacklustre performance, including a dearth of credible state faces, loss of allies, fraying social coalitions and an over-dependence on central leadership, especially on PM Modi.

While each context is unique, we believe that a larger narrative of ideological positioning underpins the BJP’s performance in state elections. The rest of the factors largely derive from this. When ideological issues are less salient, its central leadership is less effective and the dearth of state leaders more glaring. The BJP’s much-touted social engineering experiment also relies heavily on this ideological glue to keep it together. Further, it’s more difficult to make ideological issues salient as an incumbent (when both the opposition and voters are more focussed on the governance record), than as a challenger when there is no such baggage.

Also read: Art 370, CAA, triple talaq, Ram Mandir are just one cycle of Modi’s ‘permanent revolution’

The scope of ideological dictation

There are three aspects to such ideological positioning that determines the fate of the BJP. First, the ideological distance between the BJP and its key opponents determines how salient such issues become during the election campaign. In Uttar Pradesh, the BJP won the 2017 election largely by creating a popular mood against caste- and religion-based ‘appeasement’. Its messaging was thus focussed on sharpening its ideological distinctiveness from parties such as the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), the Samajwadi Party (SP) and the Congress. In Assam, it consolidated the Hindu vote by making the NRC the central issue of the 2016 election, and portraying the Congress as soft on ‘illegal immigrants’. In Tripura’s 2018 battle, the first time the BJP had a straight fight with the Left, its ideological opposite, it decisively won by expanding its vote-share from 1 per cent to 42.5 per cent.

However, elections in Delhi are a good example of the limits of this strategy. As both the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) and the BJP are equally emphatic on nationalism and corruption, ideology becomes a moot point, and the latter is forced to confront bread-and-butter issues of the electorate. The greater the ideological distance between chief opponents, the better are the BJP’s chances of victory.

Second, over-reliance on ideological distinctiveness can have diminishing returns. In a fluid, multiparty system, it only works till the time opposition parties don’t wise up and reinvent. Recent state elections have witnessed a significant narrowing of the ideological gap, consciously undertaken by parties seeking to counter the BJP juggernaut. The more parties succeed at doing this, the better their performance. This is done either by not contesting the BJP on its core issues or by proactively co-opting these. Thus, in Haryana, Maharashtra and Jharkhand, the opposition parties didn’t fall into the trap of contesting the BJP’s campaign rhetoric on Article 370, Triple Talaq and Ram Mandir and ran extremely localised campaigns focused on developmental or governance issues. In Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, the Congress went further and ran on a soft-Hindutva platform. In Delhi, the AAP adopted a similar rhetoric as the BJP on anti-CAA protesters and projected its ‘Hindu’-ness.

Third, the BJP’s success in its ethno-nationalist agenda of creating a ‘pan-Hindu’ identity has narrowed the ideological space of its state-level opponents, and forced them to confront and reinvent their existing political strategies. They have responded by making questions of development, economy and livelihood salient. Tejashwi Yadav’s daring gambit to steer clear of trademark politics in the Bihar election will give further push to this approach. The success of Left parties in the state will give further fillip to the possibility of appealing to non-identity factors. The upcoming state elections — such as in Assam, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu — could thus see new class-based cleavages being exploited.

Also read: Modi faces no political costs for suffering he causes. He’s just like Iran’s Ali Khamenei

Shift from Congress era

The BJP’s pattern of dominance — strong at national level and weak at state level — recalls the Congress period of dominance from 1967-89. Yet, whereas the state opposition parties in the latter period — Socialists, Communists, caste and regional parties — grew at the expense of Congress precisely by challenging them on ideological questions, the state parties in the Modi era reclaim their political space by remaining muted on big ideological questions. The RJD took pains to dilute its staunch social justice and secular identity by insisting, among other things, that MY stands for Mazdoor (labourers) and Yuva (youth) — and not Muslim-Yadav.

Therefore, while the electoral dominance of the Congress in 1967-89 might not have rested on ideological dominance, this is clearly not the case today. Whether the BJP wins or loses elections, the centrality of its vision in defining the electoral discourse cannot be denied. In fact, the opposition parties’ strategy of staying silent on ideological issues is the surest testament to the hegemonic nature of the BJP’s ideology.

Asim Ali and Ankita Barthwal are research associates at the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi. Views are personal.