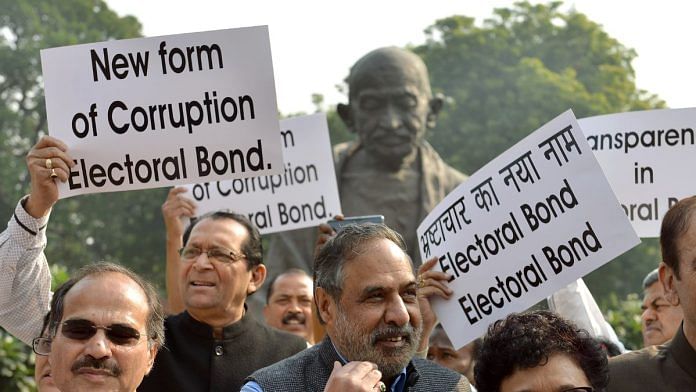

On 15 February 2024, a five-judge Constitution bench of the Supreme Court struck down the electoral bonds scheme as unconstitutional for being violative of the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression under Article 19 (1)(a). Specifically, the bench held that the scheme infringes upon the right to information of citizens concerning potential quid pro quo arrangements between donors and the political parties receiving their contributions.

At the heart of the matter are two competing rights—the right to information of voters and the right to privacy of donors. The decision has stirred up a hornet’s nest around the issue of political funding in India, especially corporate donations.

We critically examine the changes introduced by the scheme to relevant laws, the government’s rationale for supporting the electoral bonds scheme, and the central arguments of the Supreme Court. We also highlight the general concern over unlimited individual and corporate funding, as well as the potential for a state-corporate nexus that could hijack transparent and democratic governance and policymaking in India. Finally, we offer suggestions to tackle these problems.

Also Read: The real question in the electoral bonds issue is – will cash make a comeback?

Political funding in India before 2017

Political parties receive money through various channels, including individual funding via membership subscriptions, donations from trade unions and companies, as well as sales of assets and publications. Rules for transparency vary across countries. The UK, for instance, mandates declaration of donations worth over £7,500 to national parties. Additionally, it provides state funding to opposition parties to cover administrative costs (which they cannot use for campaigns), so as to prevent the ruling party from having an unfair advantage.

In India, this approach has been slightly different. During elections, all major parties get limited state funding only in the form of free airtime on state-owned electronic media. In terms of private funding, there is no limit on individual contributions while corporate donations are capped.

Before 2017, any contribution—individual or corporate—of less than Rs 20,000 to any political party in a single tranche did not require disclosure to the Election Commission of India (ECI). Such contributions were classified as unknown income. Donations exceeding Rs 20,000 were to be disclosed and classified as known income.

However, it is public knowledge that political parties have exploited this system by breaking down mega cash donations, especially black money, into smaller amounts to evade disclosure requirements. These smaller amounts are then declared as public/crowd funding generated from meetings, thereby turning it into white money. This practice obfuscates the sources of political funding and makes it difficult to trace the audit trail of cash.

Initial attempts to reform and bring transparency to political funding were made by Arun Jaitley during his tenure as law minister in Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s government. He passed a bill legitimising donations made by cheque, on the condition that they were declared to both the income tax department and the ECI. Following this, in 2010, then finance minister Pranab Mukherjee proposed electoral trusts to facilitate donations. This scheme was subsequently introduced in 2013, allowing companies to donate money through a trust. The trusts are required to submit annual reports to the ECI detailing both the contributions they receive and the donations they make to political parties.

Enter the electoral bonds scheme

Dissatisfied with previous reforms, Arun Jaitley, as finance minister in the first term of the Modi government, introduced several legal changes in 2017. These measures aimed to dispel donors’ fears about their identities being linked with the political parties they donated to. Introducing electoral bonds, he claimed that the objective was to “cleanse the system of political funding in India” and bring transparency by curbing black money and creating an alternative to cash donations.

However, the electoral bonds scheme, brought into effect through the Finance Act 2017 on 2 January 2018, further shrouded political funding in secrecy by introducing a series of amendments:

- The RBI Act was amended to allow the central government to authorise any scheduled bank to issue electoral bonds without any prior RBI approval.

- Previously, the Company Act barred political contributions fromgovernment companies as well as those that had existed for less than three financial years. The Act also imposed a cap on how much a company could donate to a political party, with a limit set at 7.5 per cent of its average net profit in the previous three financial years. Further, donations had to be disclosed in their profit and loss account. The Finance Act 2017 removed this cap on corporate funding and the disclosure provision for contributions made through electoral bonds. The only safeguard was that the contribution must be made only through a cheque, bank draft, or electronic clearing system.

- The taxation law previously required political parties to keep audited accountsand maintain a record of voluntary contributions exceeding Rs 20,000 from individuals or corporates. The law also made income of political parties through contributions and investments non-taxable, and voluntary contributions to political parties as tax deductible under the Income Tax Act. The Finance Act 2017 removed the requirement of political parties to maintain a record of contributions made through electoral bonds. It also mandated any contribution of more than Rs 2,000 to be received only by a cheque, bank draft, electronic clearing system, or electoral bond—thereby limiting cash donations to Rs 2,000 from one entity.

- The Representation of Peoples Act mandated disclosure of contributionsexceeding Rs 20,000 to the ECI. However, the Finance Act 2017 exempted contributions made through electoral bonds from disclosure to the ECI.

Since the scheme’s implementation, contributions received through electoral bonds have been categorised as ‘unknown sources of income’, irrespective of the bond’s value. The electoral bonds scheme also lacks procedural safeguards, as reflected in the data disclosed by the State Bank of India (SBI). The issues include:

- In certain cases, contributions to political parties far exceed the company’s net profits.

- Many corporate donors have a track record of raids by central agencies.

- Subsidiary companies of big corporate groups are sometimes used for political funding.

- Funding by companies registered in India but controlled by foreign entities.

What did the Supreme Court say?

In its judgment, the Supreme Court attempted to strike a balance between two competing principles—voters’ right to information and donors’ right to informational privacy. However, it did not shy away from pointing out the nexus between money and electoral democracy in India.

The court also elaborated on an underlying dichotomy in the legal regime. On one hand, the law governs contributions to political parties, but not individual candidates. On the other hand, while the law regulates candidates’ campaign expenditures, there’s no cap on political party spending.

Previously, in 1974, the Supreme Court attempted to bridge this gap in Kanwar Lal Gupta v. Amar Nath Chawla & Ors by ruling that a candidate’s election expenses should include any spending by their party on their behalf. However, this was nullified by a legal amendment in 1975.

According to reports, the upcoming 2024 Lok Sabha elections will be the world’s most expensive polls yet, with an expected cost of more than Rs 1.2 trillion ($14.4 billion). This is equivalent to the combined cost of the US presidential and congressional races in 2020. It’s unsurprising given how the legal structure has been systematically abused to institutionalise opacity in political funding.

Also Read: Electoral bonds: Lottery firm charged by ED & infra company raided by IT dept emerge as top 2 donors

The way forward

In a democratic system, where political parties are integral and make parliamentary government possible, it is important to create a comprehensive system for controlling party finances and expenditures. This is essential for building public trust and confidence in the role of political parties in the political process. Although the recent Supreme Court judgment is a step forward, it’s not a panacea for achieving transparency in political funding.

We also should not fool ourselves. Corporate funding won’t be eliminated so easily, and these entities will continue to seek policy advantages. Ensuring free and fair elections, democratic governance, and limiting quid pro quo demands political funding regulations that go beyond the age-old methods of record keeping and reporting.

We propose taking three steps. First, introduce electoral bonds without anonymity to enable an audit trail. Second, implement reasonable limits on expenditures by candidates and parties, as well as on donations from individuals and organisations in lieu of providing state funding akin to the UK. Lastly, mandate that individual and corporate donors specify the reasons for their contributions to a particular party, referencing the party manifesto. This might help make a party more accountable if it comes to power.

Dr. Shailesh Kumar is a lecturer in law at Royal Holloway, University of London and a Commonwealth Scholar. He tweets @Shailesh_RHUL.

Noopur Maurya is a former senior research fellow from JNU and the founder-director of Silicon-Route India Pvt. Ltd. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)