Increase in the need of cooling, and then burning of more fossil fuel to generate electricity, everything is contributing to climate change and gradually raising atmospheric temperature.

The grid operator that delivers power to most of Texas set an all-time peak electricity demand record this week for the month of May. Hot weather, a healthy economy and a growing population have all given Electric Reliability Council of Texas Inc. reason to expect record-breaking summer usage.

The main driver of warm-weather peaks is air conditioning. Joshua Rhodes of the University of Texas told me that half of all summer peak demand in Ercot’s territory is from air conditioning, with two-thirds of residential electricity demand coming from AC. All told, home air conditioning makes up a little less than one-third of all electricity demand in the biggest state electricity grid in the country. Providing the power to meet that need is one of the main generators of all new electrical infrastructure in Texas, Rhodes says.

But a new report from the International Energy Agency makes Texas’ demand look positively tiny as a growing, urbanizing world demands to cool itself.

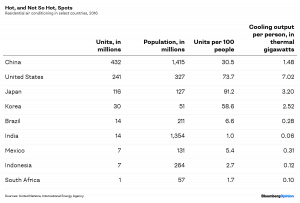

The IEA’s data shows not only how many air conditioning units there are in service today (nearly 1.1 billion worldwide) but also how uneven the distribution of cooling is. Japan has 90 residential air conditioning units for every 100 people; India has 1 per 100. South Korea has twice the number of residential air conditioners as Brazil, which has more than four times as many people. And the U.S. has more than a thousand times as much cooling output per person as India does.

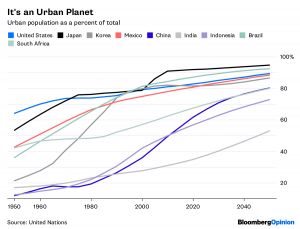

Urbanization is also pushing demand for air conditioning higher. The United Nations recently published its updated population projections. In each of the following countries profiled by the IEA in its air conditioning analysis, more than half of their populations are expected to be living in urban areas in 30 years.

As the IEA notes, urbanization and air conditioning go hand in hand: Urban downtown areas can be as much as 7 degrees Fahrenheit (4 degrees Celsius) warmer than outside their cities, and dense settlement means that there is little free movement of air to naturally cool dwellings. At the same time that air conditioning is cooling interior spaces, it is heating the outside air via exhaust, which increases the work required for inside cooling, which increases exhaust and outside temperatures.

It’s an urban vicious circle, to say nothing of its effects on climate change. The IEA expects the number of “cooling degree days” (when temperatures are above 65 degrees Fahrenheit/18 degrees Celsius) worldwide to increase by 25 percent from 2016 to 2050, making the circle even more vicious:

Climate change is raising atmospheric temperatures, directly increasing the need for cooling, which is resulting in more burning of fossil fuels in power stations to meet the increased electricity load, which is contributing, in turn, to more climate change. Breaking this circle ultimately hinges on arresting climate change; that will require curbing the amount of energy used for cooling and for other end uses, as well as decarbonising the energy mix.

Just how much can cooling demand increase electricity consumption? China’s electricity consumption for air conditioning increased 68-fold from 1990 to 2016.

Keeping a warming world cool will be a significant challenge, and as the IEA’s analysis indicates, doing it more efficiently will reduce cooling-energy demand significantly. Still, it will require even more power, new infrastructure and billions of new AC units. Next month, my Bloomberg New Energy Finance colleagues will publish their annual New Energy Outlook, which includes how air conditioning changes electricity demand patterns. Until then, keep cool. – Bloomberg Opinion