We are confronted with the inconvenient truth that governments often prove inept at both anticipating emerging trends and responding proactively. However, one assertion that should now command universal consensus is that the government’s response to technology is not just advisable but imperative. The fallacy lies in assuming that governments, like some ephemeral entity, will survive the onslaught of social transformation. History has repeatedly shown that such assumptions are dangerous, echoing the mistakes made by the French monarchy, which inadvertently paved the way for the rise of Republics.

This is not to say that governments have been immune to the challenges emerging from the technology tsunami. The 2021 global agreement on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, the 2023 Bletchley Declaration, and the 2024 EU Artificial Intelligence Act signify a foundational step towards cultivating a collective comprehension of AI’s potential and perils. However, these initial efforts lack specifics on how each country can harness and oversee technological advancement. To navigate the relentless deluge of technology, government responses must align with the intrinsic nature of the technology itself.

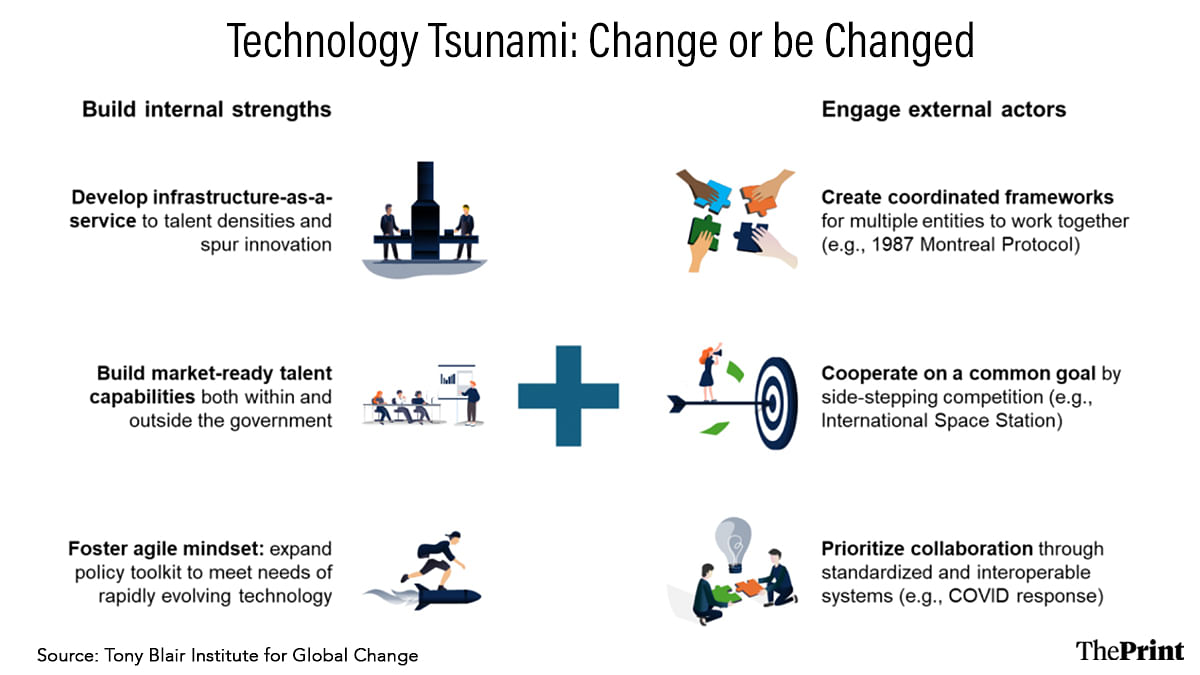

Agile management principles, championed at the start of this millennium, drove the meteoric rise of technology firms such as Amazon, Microsoft, and Spotify. It is this agility that governments must strive to amalgamate into their DNA. Rather than resorting to one-size-fits-all approaches, governments should expand their policy toolkit to meet the needs of rapidly evolving technology. For instance, archaic procurement rules that invariably slow decision-making are not suitable if countries are expected to take advantage of technological innovation that is happening at a neck-breaking pace.

Paradoxically, technology has made the world flat, yet it tends to thrive in select geographic clusters. A big reason behind this is the self-fulling prophecy of talent densities – great people attract great people. Governments should focus on creating knowledge ecosystems that cultivate talent densities both for private employment and to power government bureaucracies.

Software as a Service (SaaS), a cloud computing model where software applications are delivered over the internet, has revolutionised the software industry. It has ensured cost-efficiency for customers by avoiding upfront costs, allowing immediate access without delays from setup time, and providing financial sustainability through steady cash flows. Much in the same way, governments should invest in developing state-of-the-art-infrastructure-as-a-service, infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS) to spur innovation.

Also read: ‘Govt of the people’ has transformed into ‘administration of things’. AI powered it

Focus on cooperation

Other than changing domestically, there are also lessons from technology on how countries can work together to leverage the opportunity and tackle the challenges. TCP/IP, a standardised set of protocols, enabled communication over a worldwide network. Today, the very fabric of the internet hinges upon the presence of shared and coordinated frameworks epitomised by TCP/IP. Governments, too, must strive to develop coordinated frameworks that ensure different entities work together in an organised manner. The success of the 1987 Montreal Protocol on phasing out the production and consumption of Ozone Depleting Substances (ODS) provides a promising blueprint on that leverages timely amendments, strong enforcement mechanisms, and public awareness efforts.

At one point, Samsung – arguably Apple’s biggest competitor in the mobile phone market – manufactured core iPhone components, including display panels, processors, memory chips, and batteries. Although Apple has diversified since, it is a fact that cooperation, despite competition, is what has made the iPhone’s exponential growth progress possible. Governments should look to side-step geopolitical competition and find ways to cooperate on a common goal, even if it comes without a high degree of interaction. Just like we have largely done with the International Space Station – a prime example of international cooperation in space exploration involving space agencies from the United States, Russia, Japan, Europe, and Canada.

Finally, open access to research has a snowball effect on innovation in the technology sector. For instance, free access to genetic sequences on databases like GenBank, open software such as Apache Hadoop, or collaborative platforms like GitHub has significantly boosted the technology sector’s growth. Governments should prioritise collaboration on technology by increasing data sharing, building compatible standards, and interoperable systems. The recent Covid-19 pandemic is a good example of when the world came close to perfect collaboration. Vaccine development and manufacture for low-income countries through the Covax initiative data sharing on genomic sequencing through platforms like GISAID or the World Health Organization’s (WHO) solidarity trials where thousands of researchers in over 30 countries tested several drug candidates simultaneously are just a few examples.

All this, of course, is easier said than done. Agility challenges fundamental principles of accountability, transparency, and due process that are essential tenets of bureaucratic governance. Climbing the ladder of coordination to cooperation and finally to collaboration is not straightforward either. Coordination in the past failed in non-binding agreements, as seen in the case of CRISPR, where some signatories were suspected of violations. Cooperation, especially in collective action problems, has only had limited success in solving catastrophic challenges posed by climate change. Collaboration has been a distant dream, where securing consensus on trade issues, such as the Doha Development Agenda under the World Trade Organization (WTO), has stalled due to disagreements over policies, agricultural subsidies, and market access.

Ironically, these challenges make focusing on the technology tsunami an imperative. As leaders today decide on what to invest their political capital in, amongst the many challenges we face, from conflicts to climate and inflation to inequality, it will be a lost opportunity and costly oversight not to prioritise technology. Rather than viewing technology as an adversary to be tamed with regulations, governments must carefully craft frameworks that safeguard against unchecked growth and simultaneously promote innovation and competitiveness. But most importantly, governments must do so before they run out of the already limited alternatives.

The author heads the India practice for the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. Views are personal.

This article is part of a series on AI tech policy and impact as part of ThePrint-Tony Blair Institute for Global Change editorial collaboration.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)