Was there an entertainment industry in ancient India? The answer is a resounding YES. There was money to be made and a well-organised industry appears to have been formed.

When studying ancient human history, I tell my students that four things are important for humans—not just to survive but to thrive and maintain both mental and physical health. The first three are obvious: water, food, and shelter. The fourth, however, is less apparent: entertainment.

The prominence of the entertainment industry—from Bollywood to Hollywood, from Beyoncé to Taylor Swift—in today’s economies is obvious. Time Magazine wrote, “If Taylor Swift were an economy, she’d be bigger than 50 countries.” When Beyoncé held a concert in Sweden, the national inflation rate surged to 9.7 per cent because of the increased demand for hotels and restaurants.

Humans, even ancient humans, needed to pass the time, to keep themselves entertained as they sat around a campfire in the evenings. Storytellers, dancers, drummers, singers—these were common to all ancient societies. The question I want to address today is: How did ancient Indians entertain themselves?

A thriving industry

That there was a thriving entertainment industry is demonstrated by tidbits of information about bards and storytellers, called sutas and magadhas, found in a variety of texts, especially the Sanskrit epics. One of the main sources of information on this industry is Kautilya’s Arthashastra. Although not the only one, it is a veritable mine of information on material culture—from metallurgy to jewellery-making, from elephant care to horticulture, from military strategy to urban planning—and musical and theatrical performances, and performers.

The picture we get from Kautilya’s description is that there were numerous troupes of travelling entertainers who went from village to village, town to town, to find sponsors for their performances. Kauṭilya recorded precious information about the makeup of these troupes. Their leaders were called kushilava.

The kushilava was perhaps the central figure in ancient Indian entertainment, even within the more formal setting of Sanskrit drama. Sometimes, the term is used loosely to refer to actors in general, as in the opening scene of Sudraka’s play Mricchakatika. The director or sutradhara enters the empty stage and exclaims: “This playhouse of ours is empty! Now, where could the kushilavas have gone?”

Kauṭilya gave a list of six entertainers or actors comprising a troupe: nata, nartaka, gayaka, vadaka, vagjivana, and kushilava—actor, dancer, singer, musician, bard, and kushilava. Appearing last in the list, the kushilava appears to be the leader of the group, perhaps the producer/director. In a couple of places, Kautilya gave an expanded list of nine members with the addition of plavaka, saubhika, and caraṇa—rope dancer, dramatic storyteller, and troubadour.

Although it is not altogether clear, these terms probably referred to categories of artists rather than individuals, much like today’s orchestras consisting of artists playing violins, flutes, drums, and the like. So, a troupe may well have consisted of many more than six or nine individuals. It is also probable that some performances may have used fewer performers.

Also read:

Could entertainers be dangerous?

Given the itinerant nature of these groups, Kauṭilya considered (?? why past tense) them as posing a security threat to the state—just like itinerant ascetics and monks. They could provide good cover for secret agents of foreign kingdoms. Kauṭilya (Arthashastra 7.17.34) himself mentioned using “actors, dancers, singers, musicians, storytellers, minstrels, rope dancers, and jugglers” to infiltrate the ranks of an enemy king. That’s why these groups were closely supervised.

Kauṭilya also required entertainers not to cause any hindrance to agricultural work in the countryside. He did not think that hard agricultural labour could coexist with public entertainment extravaganzas. Further, like their religious counterparts, the entertainers were advised to suspend travel during the four months of the rainy season.

These performers were also employed by the royal household; kings liked to be entertained by them. Kauṭilya (5.3.15) mentioned that actors received 250 panas as salary, while those who manufactured musical instruments received twice that amount. Here, for the first time in Indian history, we get some information about craftsmen who supported the entertainment industry by supplying musical instruments.

Performances within the royal palace required additional security. Kauṭilya (1.21.16–17) wrote, “Actors should entertain the king without employing performances involving weapons, fire, or poison. Their musical instruments should remain within the palace, as also the ornaments of their horses, carriages, and elephants.” These restrictions reveal that performances may have contained acts using weapons and fire. It appears that these performances were probably variety shows with music, singing, jugglery, storytelling, and magic shows.

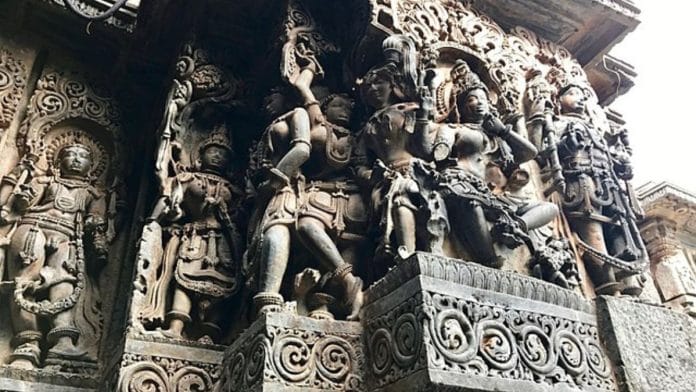

Also read: When did large Hindu temples come into being? Not before 500 AD

No freeloaders, please

Turning from performers to performances, two terms were used in the literature: samaja and preksa. The former were festive events similar to a fair or carnival. The latter, preksa, were specifically musical and theatrical performances sponsored by individuals, groups, or whole villages.

These performances were associated with the six entertainers headed by the kushilavas, along with rope dancers, jugglers, and troubadours. Sponsorship of shows by a village or town fell under the legal category of samaya or convention whereby all would agree to underwrite a project.

When an individual belonging to that community did not contribute his share, he was in breach of the convention and could be prosecuted. Kauṭilya (3.10.387–38) had this interesting observation about people who tried to freeload: “When someone does not give his share to stage a show, he along with his people shall not see it. For listening or viewing it secretly, moreover, he should be forced to pay double his share.”

It appears that at least some of these performances were staged at night. One of the reasons for authorised movement at night within a city, when generally there was a night curfew, was to see a performance. It also appears that at least some of the performances were segregated by gender: Some were reserved for women and some for men.

A wife, for example, is fined for going to a show intended for men (3.3.21–22): “For going during the day to a women’s show or excursion, the fine is six panas, and for going to a men’s show or excursion, twelve panas; double that, if it is done at night.”

Also read: Rome to Kabul, ancient India was a global player in trade. Kautilya’s Arthshastra tells all

A low social position

Religious texts assigned entertainment activities, including music, to individuals of mixed varnas. So although they were socially and culturally significant, members of the entertainment profession in general had a low reputation. They were looked down upon, especially by the mainstream Brahmanical tradition, and probably occupied a low social position.

Among those not invited to an ancestral offering (shraddha) were those who played musical instruments and drums, and engaged in dancing and singing (Gautama Dharmasutra, 15.18). Manu (8.65) forbid kushilavas from being witnesses in legal proceedings.

Kauṭilya (2.27.25) seems to suggest that men in the entertainment industry pimped their wives. The connection of entertainers with the sex trade is indicated by Kauṭilya’s statement (2.27.7) that sons of courtesans in the royal service should be trained in the craft of kushilava from the age of eight.

Unfortunately, the information we have about ancient Indian entertainers comes from those who sought to regulate or disparage it. We have no texts written by actors or musicians, and Kauṭilya provides the most dispassionate account. It is clear, however, that the entertainment industry was as vibrant and strong in ancient times as it is in contemporary India, with specialisations in terms of the roles of the actors and the musical instruments employed.

Patrick Olivelle is Professor Emeritus of Asian Studies at The University of Texas at Austin. He is known for his work on early Indian religions, law, and statecraft. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)