Legal barriers, such as the blanket 20-week gestation limit, no mention of unmarried women in the clause of contraceptive failure, the need for physician’s consent – all constrain and deny women reproductive justice.

According to a Worldometers projection, the world has witnessed 36.4 million childbirths since the beginning of this year, and 10.8 million induced abortions. The birth of a child usually gets attention, support and celebration. Abortions usually get judgment, stigma and punishment.

Abortions are commonplace. According to studies published in The Lancet last year, an estimated 56 million abortions took place globally each year between 2010 and 2014, with 15.6 million induced abortions in India in 2015. While their accessibility and availability are a major public health necessity, for me, providing a safe abortion is about reproductive choice and entitlement, rights and justice.

In August 2008, Niketa Mehta approached the Bombay High Court with a request to terminate her 25-week pregnancy as her ultrasound showed a severely abnormal foetal heart condition. She was denied an abortion and eventually suffered a miscarriage. It’s been 10 years since she was denied reproductive justice. It has been 15 years since our 47-year-old abortion law was last amended to address challenges that hinder access to abortion services. As further amendments to the law await Cabinet approval, women all over the country continue to struggle for access to safe abortion services.

Abortion has been legal in India since 1971, under the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, which is liberal in its provisions. However, it’s not without limitations, and the need to amend it cannot be emphasised enough. The horrific case of the 10-year-old rape victim being denied permission to abort shook the nation last year and reignited the conversation about the need to address the gaps of the abortion law.

The case forced the government and the Supreme Court to take note of the challenges women face in this country for a routine, yet much-needed, procedure.

It also encouraged an MP to raise a question in the last Parliament session about the estimated time it would take for the new bill to be tabled and passed.

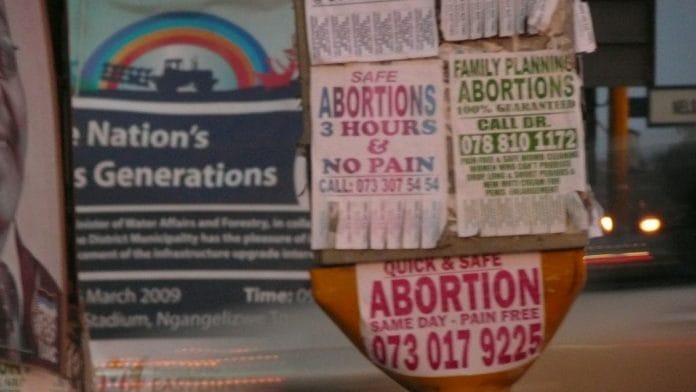

However, movement on this front remains slow and unmotivated. As barriers to access continue to exist, women are compelled to seek abortion services from unqualified practitioners, illegal providers or ‘quacks’, which may often result in medical complications and adverse health implications.

Amendments to the law address specific gaps identified back in 2006. The MTP Act allows a woman to terminate her pregnancy under certain conditions within 20 weeks; it has to be done by a registered medical practitioner at a registered medical facility. However, it is not the right of a woman – which means she cannot go into a medical facility at any stage of her pregnancy and request for an abortion. Legal barriers – such as the blanket 20-week gestation limit, no mention of unmarried women in the clause of contraceptive failure, the need for physician’s consent – all constrain and deny women reproductive justice.

The struggles of women (and often the providers of these services) do not end here. In addition to the lack of facilities, insufficient infrastructure and stigma, and the overlap and conflation of other laws with the MTP Act only add to the challenges.

The Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act, 1994, and the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012, aim to address, curb and eliminate the practice of sex selection and the increasing incidence of child sexual abuse in the country, respectively. However, in the case of the PCPNDT Act, there has been an overzealous attempt by government authorities to clamp down on all second trimester abortions. This is driven by the belief that all second trimester abortions are for sex selection, a belief that is not backed by evidence.

On the other hand, the POCSO Act directly contradicts the confidentiality clause of the MTP Act – with providers obligated to report any case of under-18 pregnancy to police. Besides the extreme effect of criminalising all sex under the age of 18, it compromises the identity of the girl who wants an abortion and increases the risk of her not approaching a qualified provider to avoid reporting.

However well-intentioned and necessary these laws are to address and combat social evils, both hinder access to quality, safe abortions services, make providers hesitant, and impinge on a woman’s right to privacy. Activists for a cause must be cautious of working in silos to avoid collateral damage to other, equally important issues.

As a gynaecologist, I meet women – married, unmarried and underage – who require these services. They are well within their rights to decide whether they wish to continue their pregnancy. As a society, we need to accept the realities of the 21st century, where women have the right to make decisions about their sexual and reproductive health.

In fact, the Supreme Court of India, in August 2017, reinforced this right to choose and placed abortion under the constitutional right to privacy.

The amendments to the MTP Act provide women the opportunity to exercise their right to choose. It proposes allowing abortion on request until 12 weeks, increasing the threshold gestation limit from 20 to 24 weeks for vulnerable groups such as single women and victims of rape, removing the gestation limit completely where the foetus is diagnosed with substantial abnormalities, and reducing the number of physician opinions required, from two to one, in the second trimester.

The amendment also proposes to widen the provider base for early medical abortion to include non-specialist mid-level providers – a change that is urgently required to address the dearth of providers in underserved areas.

These changes to the law will not only increase access to abortion services but also reduce the burden of unsafe abortions on maternal mortality, and allow the government to showcase its commitment to women’s empowerment. There is an urgent need for the Cabinet to review these amendments and table them in Parliament.

Having an abortion is not about how the pregnancy occurred or whether contraception was used. And it is in no way related to a woman’s background or religious beliefs. Having an abortion is about being a woman who has decided to exercise her choice.

Since it is the woman who shares her body and her life with her pregnancy, the decision to continue or terminate one can only be hers. It’s time we let women make their own choices. It’s time to ensure reproductive justice for all women in our country.

Dr Nozer Sheriar is the former secretary general of the Federation of Obstetric & Gynaecological Societies of India (FOGSI). He serves on the board of the Guttmacher Institute and Ipas.

Apart from the suggestion on removal of the 20 week limit, I agree with everything else the doctor has written. After 20 weeks, the foetus becomes a live baby. It’s murder to abort it after 20 weeks unless the health of the mother is at risk or there is some severe complication. In case, a rape victim wants an abortion after 20 weeks, she can be given the option of giving birth and then giving the baby up for adoption or to an orphanage. However, the baby should not be murdered.

Common sense reality tells us that a mother does not own the child in her womb—the ties are not ties of ownership but ties of deep belonging. Her tiny daughter or son belongs to her and she belongs to her child. It is the natural intimacy of two human beings, not of owner and object, or master and slave.

It’s not just “her” body—in every pregnancy there is another body, an active little body, a tiny daughter or son, a tiny somebody, deserving a mother’s protection, a father’s protection and the protection of the law.

A mother’s unborn child is already here, already in existence, being protected and nurtured in her/his mother’s womb.

The truth is that we women have no “right to choose” to have the abortionist inflict a deadly harmful procedure on another human being–in our power and under our care–no matter how small or dependent or ‘unwanted’. No human being has ownership and killing rights over another human being.

Adequate nutrition, the protective environment of the mother’s womb, and benign medical care are “basic rights” of every new human being and because of their fundamental necessity to the nurturing of life; they are the unborn child’s minimum and reasonable demands on her/his biological mother, father, their families and their community.

A mother nurturing her little daughter or son in her womb is exercising her natural duty of care. It is just the ordinary care owed by every mother to her child–nothing extraordinary–just exactly what our reproductive systems are equipped to do. It is just what our mothers did for us and what our grandmothers did for our mothers and what our great-grandmothers did for our grandmothers.