Here’s how the 16th-century Suleiman Charitra begins: “There was once a mighty lord of Ayodhya. In splendour and prowess, he was like Indra, the king of the gods… Brave and devoted to public welfare, he was the famous King Ahmad, always kind and merciful, a bright jewel of the Lodi line.” An extraordinary Sanskrit poem, lush with erotic rasa imagery, it translated the Biblical story of Solomon into India’s ancient language of kings and priests.

Yet, the Suleiman Charitra was by no means unique. It belonged to a world where Vijayanagara Sanskritists praised Chauhan allies of the Mandu Sultans, while English Jesuits wrote Konkani Puranas about Jesus. This uniquely Indian syncretism wasn’t simply motivated by devotion. India’s historical diversity developed from hard-nosed politics and astonishing inventiveness, which helped make it a global juggernaut unique for its time.

India between empires

Empires dominate our imaginations. Who doesn’t like to see maps painted with their own colours? But the fact is that in South Asia, it is moments of imperial disintegration — when regional identities and ideas assert themselves — that give rise to the most brilliant cultural moments.

Consider Northern India in the 15th century CE. The power of the Delhi Sultanate had just been shattered by the Central Asian warlord Timur, who massacred the mostly-Muslim populace of the city. From Gujarat to Bengal, Indian societies and religions were in churn, as new communities obtained political power and sought legitimacy. They had many avenues to do so. For example, a clan of militarised Gujarati peasants, who had served in the retinue of Firuz Shah Tughlaq, decided to convert to Islam, supposedly on the initiative of a Sufi saint. (Some scattered sources also called them Rajputs and descendants of Ram) This clan declared Gujarat an independent Sultanate, which they ruled from their capital, Ahmedabad.

Other minor clans built forts atop hills and sought a position in the Sanskritic caste hierarchy. In the edited volume After Timur Left: Culture and Circulation in Fifteenth-Century North India, historian Aparna Kapadia studied Gangadhara, a poet from the South Indian Vijayanagara Empire. Gangadhara worked for Gangadas Chauhan, a minor chieftain of Champaner. The poet had arrived there via Ahmedabad, where he claimed to have defeated rival Sanskrit poets at the Sultan’s court.

The Chauhans commissioned Gangadhara to integrate them into the world of Sanskrit court culture, which he did by romanticising a conflict they had with the Gujarat Sultans. In his poem, the Ganga-Dasa-Pratapa-Vilasa-Natakam, he explains how Gangadas Chauhan exhibited ancient kshatriya values by refusing to give up political refugees to Sultan Muhammad of Gujarat. The Sultan besieges Champaner and kills these refugees despite Gangadas’ valiant resistance, but is unable to take the fort. Finally, the situation is resolved when the neighbouring Sultan of Mandu attacks Gujarat.

The Sultan’s kshatriya vassals advise him, in Sanskrit: “The protection of one’s own territories is the king’s foremost task”. And so the Sultan retreats, and the Chauhans thank the gods for Mandu’s intervention. What this story achieves, quite deftly, is connecting the Champaner Chauhans to ancient Sanskritic notions of royal behaviour, while also justifying their balancing game with Sultanates — and acknowledging the Sultanates as serious and legitimate overlords.

Also read: How did Durga’s popularity survive Mughal & colonial rule? Bengali zamindars made it happen

Sanskrit continued to evolve

Gangadhara’s work also shows us that Sanskrit court poetry was alive and well in the Sultanate-dominated world of 15th-century northern India. Little kings were still using it to legitimise themselves, even as powerful rulers inclined to the political prestige of Sultanate systems. Sultans, it seems, were well aware of Sanskrit, at the very least hosting and employing Sanskrit poets. Indeed, the 15th century saw substantial Sanskrit engagement with Sultanate religion and language, despite the oft-repeated myth of relentless persecution.

As distinguished translator A.N.D. Haksar writes in his introduction to the Suleiman Charitra, there was the Parasi-Nama-Mala, a Gujarati Sanskrit-Persian Lexicon, and the Katha-Kautuka, a Hebrew legend rendered into Sanskrit via Persian. The 15th-century Purusha-Pariksha of Vidyapati, studied by historian Sunil Kumar (After Timur Left), even depicts Muhammad bin Tughlaq as an ideal Sultan, using a story of young kshatriyas vying for his favour to impart lessons on courtly behaviour to new warrior clans. Parallel processes were at work in South Asian Persian and Arabic literature as well.

What we are seeing is not a devotional syncretism between a unitary “Hinduism” and “Islam”. This myth, much admired by liberal India and trashed by the Right, doesn’t capture the uniqueness of what was happening in the 15th century. Its babble of texts and ideas is because a hodgepodge of spiritual, military and literary entrepreneurs — of many faiths, cultures, and ethnicities — were building alliances and finding a place on the ladder of South Asian politics. This led to an astonishing intellectual open-mindedness, at a time when Ming China was becoming increasingly closed off to the world, and Europe was preparing for brutal, religiously-justified expansion into the Americas.

Also read: Port Blair’s new name ‘Sri Vijaya Puram’ isn’t historical or decolonial. It’s politics

The Suleiman Charitra

India’s developing syncretism was often contradictory and uneven. By the early 16th century, the Lodi dynasty had managed to establish some authority over the upper Gangetic belt; while its official policy discriminated against Hindus, its regional governors issued Sanskrit edicts in sites such as Bayana in Rajasthan. It was also under Lodi auspices that many Hindu holy orders settled in Vrindavan. And in Ayodhya, a dynasty of Lodi governors commissioned the kshatriya poet Kalyana Malla to write the Suleiman Charitra, a Sanskrit Bible story about King David, who lusted for his general’s wife, Bathsheba.

As Haksar writes, the Charitra is quite unashamedly suffused with Sanskrit literary ideas, particularly the sringara rasa, the romantic — even sexual — essence. The beauty of the naked Bathsheba (rendered into Sanskrit as Saptasuta) is explicitly described, as is her seduction by, and intercourse with, David. This detail isn’t present in the Bible, nor was it in the Arabic or Persian commentaries that Kalyana Malla must have read. All of these are his innovations, intended to bring this Biblical story into line with Sanskrit court culture.

Malla describes his patron, Lad Khan, as an “expert in the science of love”, a skill regarded most highly by older Sanskrit literature such as the Kamasutra. We know from other sources that Lad Khan was a generous if feckless chap; possibly dyslexic, he tended to leave his officers to do the hard work while he enjoyed the cultured entertainments of the court. There’s no doubt he was well-educated in Persian and Arabic literature, particularly related to the Quran. So it is quite telling that he commissioned a Sanskrit text bridging these worlds: not just a literal translation but a cultural one.

Also read: Torture, death, fines — how Arthashastra guided ancient kings on addressing crime & dissent

Mughal translations

This impulse to bridge worlds, to harness them for patrons’ interests, continued into the 16th century, when North India’s many regions were integrated into the Mughal Empire. The Mughal court commissioned multiple Persian translations of the Mahabharata and Ramayana, and generally — if unevenly — allowed religious freedom at a time when Europe was dissolving into sectarian conflict during the Protestant Reformation.

Scholar and poet Ranjit Hoskote, for example, has discussed the work of Thomas Stephens, an English priest who settled in Goa and wrote the Krista Purana, an 11,000-verse ‘history’ of the world from its creation to the death of Jesus. Written in Konkani and Marathi, it was set to the metres of Bhakti poetry. In doing so, Hoskote points out, Stephens was not only acting in contradiction to the Goan Inquisition: he also preceded the Vatican’s 1960 edict that preaching should be sensitive to local cultures by some four hundred years. He developed a vocabulary for Indian Christians that is still used today, such as the term “jnanasnana” for baptism.

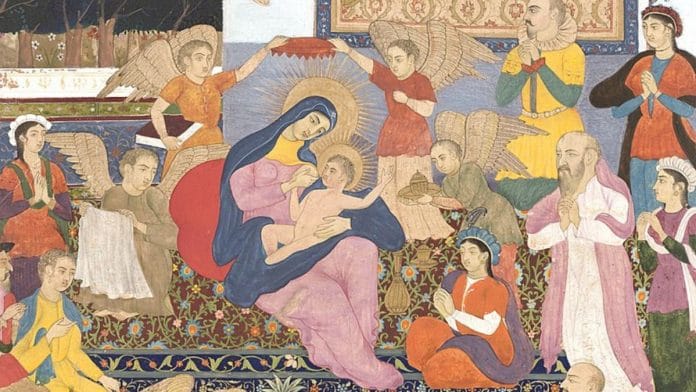

Meanwhile, Stephens’ contemporary, Jeronimo Xavier, was trying to convert Indian elites at the Mughal court, collaborating with the Indian scholar Maulana Abdus Sattar Lahori to produce a Persian biography of Jesus, the Mir’at al-Quds. According to Hoskote, this is the first modern biography of Jesus ever written, drawing and interpreting a variety of texts, and tailored to Indian Muslim tastes through effusive praise of the venerated Virgin Mary.

Mughal court painters, many of them Hindu, decorated it with illustrations inspired by the first-ever European prints. Ironically, such a text could not have existed in Europe at the time: in many ways, it was only India that possessed the political environment and intellectual prowess to even imagine such a project. Yet the Mir’at did not succeed in winning over Mughal converts — despite the novelty of this project, the Mughals were rightfully suspicious of the black-and-white worldview of the Jesuits, ill-suited to the diverse aristocracy they ruled over.

The point of all this is not to eulogise the bonhomie of premodern elites – Hindu, Christian, Muslim, Persianate or Sanskritic. What I want to argue is that syncretism and tolerance are not an inbuilt feature of Indian civilisation, which we can take for granted, pay lip service to, or chip away at for political profit. Despite many efforts at persecution and conversion, syncretism developed again and again through serious political and intellectual commitment. Invariably in Indian history, this has proved worth the effort, because it allowed for the influx, development, and spread of invigorating new ideas and possibilities — ideas uniquely Indian.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of ‘Lords of the Deccan’, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

One time you argue that there existed a syncretic culture thats part of Indian civilization which was mix of unitary religions and then you say it did not exist but was created due to politics of then elites have some clarity man. Why don’t you write about commoners and their beliefs at that time instead of some obscure texts written by some nameless poets to impress foreign rulers?