Kerala is better equipped to rise anew from the calamity than any other part of India.

When S. Gurumurthy insinuated that the Kerala flood disaster was somehow related to allowing women into the Sabarimala temple, he revealed a failing that afflicts even mahatmas in India.

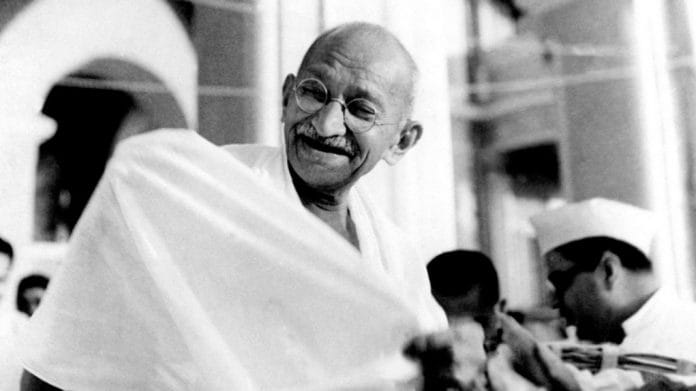

Gandhi blamed untouchability and caste discrimination for the earthquake that struck Bihar in 1934, causing a famous exchange of letters and a civilised but public disagreement with Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore chastised Gandhi for promoting superstition. Gandhi remained unapologetic, claiming that even if he was wrong to suggest that human conduct had caused natural disasters, as long as it was for a good cause – fighting untouchability – it was justified. Clearly, the Mahatma’s belief in the supernatural outweighed his own professed philosophy of ends not justifying the means.

But Tagore wasn’t the only one who chastised the Mahatma. Guess who said the following:

“There was a massive earthquake in Lisbon in the 18th century. The religious leaders of Europe preached to the people that the earthquake was the result of the Protestant perfidy against the religious beliefs of the Roman Catholics… It was in reaction to these reasons that the people decided to protect themselves against future earthquakes by trying to finish off the Protestants.

Such naive people were incapable of even understanding that there were physical explanations for earthquakes, let alone trying to use seismology to design machines that could perhaps help them predict the risk of an earthquake. Europe could truly embrace the machine age only when its religious beliefs were demolished by the scientific approach.

But in India, even someone as influential as Gandhiji swears by his “inner voice” to say that the Bihar earthquake is a punishment for the caste system. And that he is still waiting for his inner voice to tell him why Quetta was rocked by an earthquake.

And then there are Shankaracharyas and other religious leaders who swear by the religious books that the earthquake was caused by attempts to do away with the caste system.

What can one say about the religious naiveté of the ordinary people in a country when its prominent leaders hold such views? Europe is in the year 1936 while we are in the year 1736.”

These are the words of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, the intellectual fountainhead of Hindutva.

Also read: What would have happened to Mahatma Gandhi in the times of Cambridge Analytica and Facebook?

I must thank Niranjan Rajadhyaksha for translating Savarkar’s Marathi article in the magazine Kirloskar, wherein “he argued that India would continue to lag behind Europe as long as its leaders believed in superstition rather than science”. Savarkar certainly wouldn’t approve of his modern-day followers adopting Gandhi-type superstitious beliefs.

Savarkar distilled the general point about the Lisbon earthquake, but he seems to have confused the details.

After the Portuguese capital was struck by a devastating earthquake on All Saints’ Day in 1755, the Catholic religious establishment put forth the view that the disaster was divine punishment for human sin. This angered the Marquis of Pombal, the Portuguese king’s reformist chief minister at that time, who had set upon rebuilding the city with steely determination.

Pombal went after the Jesuits who got in his way to the extent of, ironically, setting the Inquisition on them and burning Gabriel Malagrida – a prominent pamphleteer who’d championed the divine punishment theory – at the stake. Pombal carried out reforms that brought Portugal into the Age of Enlightenment: modernising education and industry, while rebuilding the city’s ruined infrastructure.

Also read: In Kerala flood war room, clockwork efficiency is the order of the day

Pombal was no doubt a ruthless autocrat, but he is relevant to the current flood crisis in Kerala. No, not the bit about burning propagandists at the stake, but rather the bloody minded focus on the task of rehabilitation and rebuilding. “What now? We bury the dead and feed the living,” goes an apocryphal quote attributed to him. Pombal did more than that – he used the reconstruction as a fulcrum for national transformation.

Today, as we despair about the enormity of the calamity that has struck Kerala, we can take heart from the empirical evidence that shows natural disasters can improve long-term economic growth. The crisis and its immediate aftermath will indeed be painful, the human and economic losses severe, and the post-crisis management challenges immense. Yet, Kerala is better equipped to rise anew from the calamity than any other part of India.

That’s because of its high level of human development: physical capital may well be destroyed by the flood, but the immense human capital that the state enjoys is relatively unscathed. It also has good social capital to rely on. With the right kind of post-crisis reconstruction framework, Kerala can aspire for higher levels of prosperity and human development.

Also read: Can India have a liberal mass hero ever again?

In a landmark cross-country study over 30 years, Mark Skidmore and Hideki Toya found that natural disasters can have a positive impact on long-term economic growth, and one standard deviation in climatic disasters raised annual economic growth rate by 0.47 per cent. In another important study, Aaron Popp found that natural disasters affect economic growth through “technology, human capital accumulation, physical capital accumulation, and the natural resource stock. All four macroeconomic variables help increase long-run growth”. Post-crisis recovery, therefore, should promote these ingredients of growth. Healthy recovery needs good institutions that, again, Kerala can justifiably boast of.

No study of such a nature can be conclusive. Nor is it a given that positive effects will kick in over the long term. Even so, this knowledge offers us encouragement in our moment of distress. For, while the moral conduct of humans has little to do with natural events, it is entirely within our power to come out better and stronger from our misfortunes.

Nitin Pai is director of the Takshashila Institution, an independent centre for research and education in public policy.

PRINT IS NOTHING BUT ANTI MODI FAKE PROPOGANDA WEBSITE.