The World Bank’s recently released International Debt Report highlights a worrying external debt position for low and middle income countries (LMICs). While economic activity has rebounded in these economies post the pandemic, the debt accumulated during the pandemic has continued to escalate. By the end of 2023, the overall debt stock of LMICs has surged to USD 8.8 trillion, up 2.4 percent from the previous year.

Another concerning feature is the record rise in the debt servicing costs of these countries. The total debt servicing costs (principal plus interest payments) of all LMICs rose to an all-time high of USD 1.4 trillion in 2023. The sharp rise in the debt servicing cost is due to surge in debt, rise in interest rates and depreciation of local currencies against a strong US dollar.

Rise in debt stock driven by both short & long-term debt

With the exception of 2022, LMIC’s reliance on short-term debt has risen since 2016. While countries undertook short-term debt during periods of economic uncertainty due to lack of long-term funding options, it was also used as a debt management policy tool amid high interest rates to avoid the higher interest costs associated with long-term debt.

While short-term debt increased by 3.4 percent to USD 2.3 trillion, long-term debt increased by 2 percent to USD 6.5 trillion. Short-term debt accounted for 26 percent of the total external debt and the share has remained stable over the last three years.

Depending on the nature of the borrower, the long-term debt is classified as public and publicly guaranteed external debt (held by the public sector, including government and state-owned enterprises), and private non-guaranteed debt (held by private debtors, not guaranteed by a public entity).

The public and publicly guaranteed debt accounted for 59 percent of the overall long-term external debt in 2023.

Also Read: Balancing inflation & growth, managing rupee: New RBI governor’s docket will be full of challenges

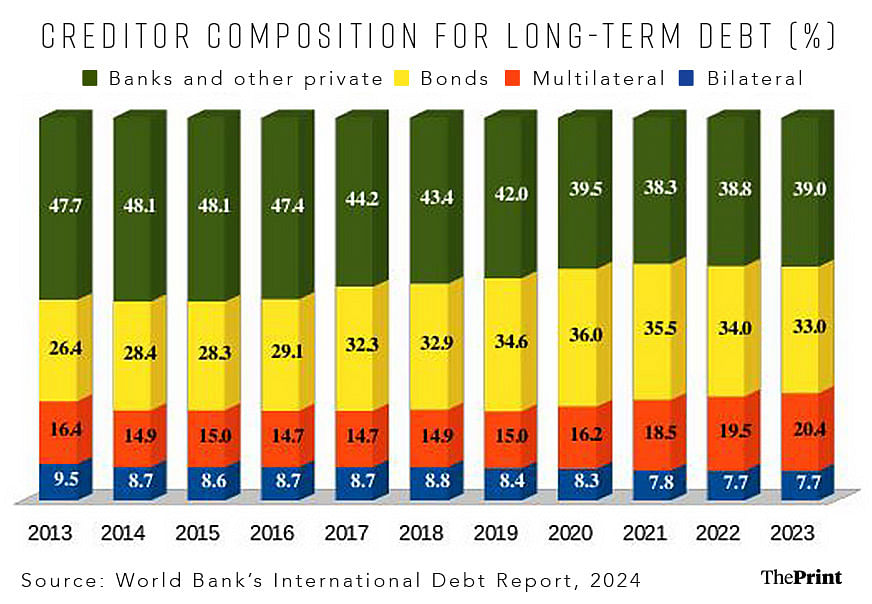

Creditor composition of external debt

Since 2007, the developing economies’ financing landscape has been gradually changing.

Lower debt from multilateral creditors and traditional Paris Club creditors has been offset by increased access to funding through private creditors or international capital markets, and non-Paris Club creditors.

In principle, access to new sources of finance can help compensate for the relative decline in concessional financing. However, this changing landscape can present challenges as access to private debt comes at higher interest rates and may increase the risk of unsustainable debt. The debt servicing burden could also rise as its maturity is generally lower than financing from multilateral lenders.

The share of external debt owed to private creditors (banks and bondholders) increased consistently from 2013 till 2019. The share of private creditors in the long-term external debt stock rose from 74 percent in 2013 to 76.7 percent in 2019. Since then, the share has seen a decline, dropping to 72 percent in 2023.

Concomitantly, the share of multilateral lenders has increased in the post-pandemic period. The share of multilateral lenders has increased from 14.9 percent in 2020 to 20 percent in 2023.

Multilateral creditors, including International Monetary Fund, World Bank and regional development banks, stepped up funding and provided emergency relief and balance of payments support to countries in times of crisis. In 2023 alone, lending by multilateral creditors rose by 6.8 percent, while that of private creditors rose just 0.8 percent.

The landscape of bilateral creditors has also evolved over the past decades. Typically, Paris Club creditors were the most dominant sources of funding to heavily indebted poor countries. In recent times, the non-Paris club members, such as Saudi Arabia, India and China, have become important bilateral lenders.

After a dip in the last two years, bilateral creditors returned to lending to LMICs through a diversified mix of lending instruments. This includes bilateral currency swap lines, under which, two central banks agree to exchange their currencies in order to provide foreign currency liquidity to domestic commercial banks, or hold as reserves to meet temporary balance of payments needs.

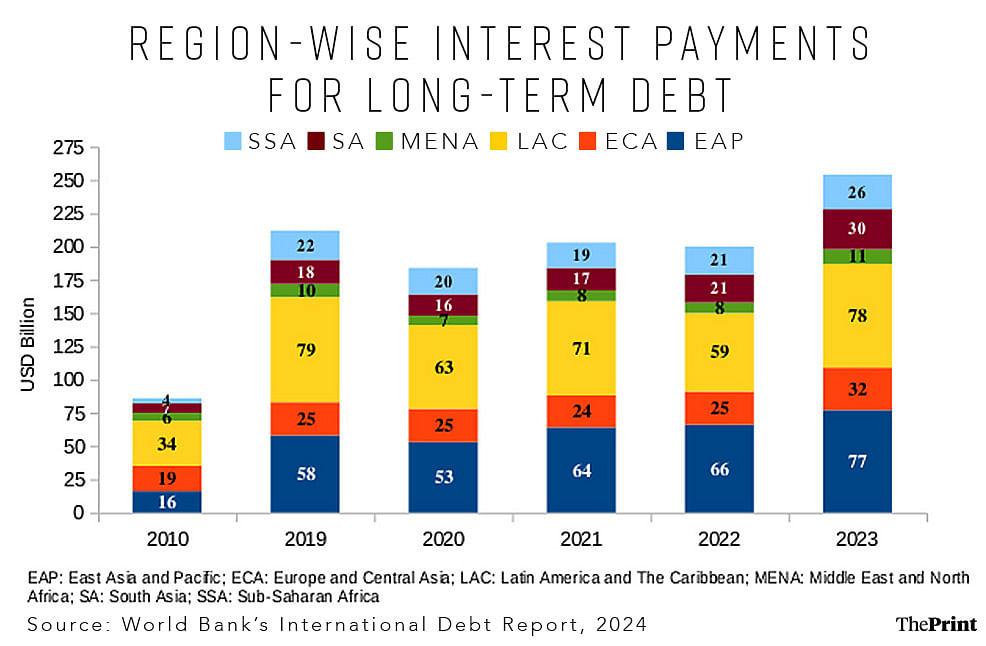

Surge in debt servicing

The most concerning feature of the external debt landscape has been the surge in debt servicing payments for LMICs. The tightening of the US monetary policy in 2022 and 2023 led to an increase in the value of the US dollar relative to other currencies, and made repayment of foreign currency debt costly for LMICs as their local currencies depreciated.

While principal payments rose by 12.9 percent, interest payments rose by a staggering 41.7 percent in 2023. Since most of the debt is contracted at variable interest rates, fluctuations in global interest rates led to an increase in interest burden by LMICs, particularly excluding China.

Further, all new debt issued during this period was contracted at higher rates. The overall increase in LMICs’ debt servicing costs is also a result of these countries rapidly accumulating external debt stock over the last decade.

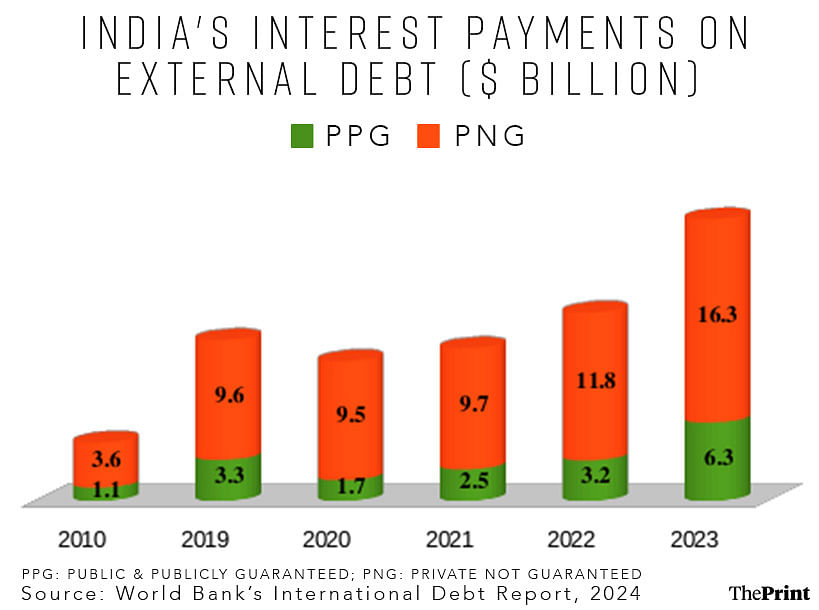

India saw noticeable rise in interest payments

The South Asia region, in particular, saw the biggest yearly increase in interest payments.

Notably, India and Bangladesh saw a steep surge in interest payments in 2023. Interest payments rose for both public and private sector debtors. For India’s public sector debtors, interest payments rose by almost 93 percent in 2023.

Similar concerns are borne out by India’s external debt report for 2023-24. India’s debt servicing outlay increased significantly over the last year, standing at USD 63 billion in FY 2023-24, compared to USD 49.2 billion in FY 2022-23. This was a 28 percent increase on account of both principal and interest repayments.

The large increase in interest payments was due to rise in the payments to official creditors and those of commercial borrowers. In particular, the implied interest rate on commercial borrowings rose by almost two percentage points from 5.2 to 7.1 percent over the previous year.

With the possibility of a sustained rise in the dollar, companies are opting for cross-currency swaps to convert part of their debt into euro or Japanese yen to trim borrowing costs.

Currently, India’s external debt is well placed as its short-term constitutes a small proportion of the overall debt. Foreign exchange reserves (around 97 percent of total external debt) are adequate.

However, debtor LMICs, including India, should remain watchful as any adverse global developments (such as unexpected inflation or growth slowdowns) and sharp rise in the US dollar—amid a possible end of the interest rate easing cycle—could have negative consequences for their external debt positions.

Radhika Pandey is associate professor and Utsav Saksena is a research fellow at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

Views are personal.